That’s Just Your Opinion

Rod Dreher joins Justin McBrayer in fretting that we are teaching students there are no “moral facts”:

A few weeks ago, I learned that students are exposed to this sort of [morally relativistic] thinking well before crossing the threshold of higher education. When I went to visit my son’s second grade open house, I found a troubling pair of signs hanging over the bulletin board. They read:

Fact: Something that is true about a subject and can be tested or proven.

Opinion: What someone thinks, feels, or believes.

This comes from Common Core standards, McBrayer says. What’s wrong with this? McBrayer goes on:

First, the definition of a fact waffles between truth and proof — two obviously different features. Things can be true even if no one can prove them. For example, it could be true that there is life elsewhere in the universe even though no one can prove it. Conversely, many of the things we once “proved” turned out to be false. For example, many people once thought that the earth was flat. It’s a mistake to confuse truth (a feature of the world) with proof (a feature of our mental lives). Furthermore, if proof is required for facts, then facts become person-relative. Something might be a fact for me if I can prove it but not a fact for you if you can’t. In that case, E=MC2 is a fact for a physicist but not for me.

But second, and worse, students are taught that claims are either facts or opinions. They are given quizzes in which they must sort claims into one camp or the other but not both. But if a fact is something that is true and an opinion is something that is believed, then many claims will obviously be both.

It’s pretty shocking to read the examples he found, and the evidence from his own child’s moral reasoning that this instruction is having a corrosive effect. McBrayer concludes:

In summary, our public schools teach students that all claims are either facts or opinions and that all value and moral claims fall into the latter camp. The punchline: there are no moral facts. And if there are no moral facts, then there are no moral truths.

This kind of nihilism cannot work in the real world, the world that they will encounter, the philosopher says. Read the whole thing. It’s important.

Well, I suppose it is important – but are we entirely sure that second-graders are prepared to handle Gettier counterexamples?

More seriously, let’s look at a very real-world second grade type example, and see where facts and opinions enter into the discussion.

Eddie takes Billy’s cookie without permission. Billy protests to the teacher. What are the facts of the case?

- Eddie took the cookie.

- The cookie belonged to Billy.

- Billy did not give Eddie permission.

These are all facts of the case. If they can be established, then we know what happened.

To know what consequence follows, you need to know some other facts – facts of law. In this case, these are:

- Taking other people’s things without permission is not allowed.

- The teacher is the one who determines what happened, and what the consequence is if a student does something that is not allowed.

Those are the facts of the law: matters of the rules and who has jurisdiction over a given question. The teacher duly establishes the facts, and sends Eddie to the principal’s office.

What would be an example of an opinion? Well, Eddie could say that his punishment of being sent to the principal’s office is unfair, because he gave Billy a cookie last week so Billy has to give him a cookie this week. That’s an opinion. It’s certainly not a fact.

It’s also moral reasoning, and it should properly be engaged, so as to develop Eddie’s moral reasoning further. The teacher should say that he understands it feels unfair that Billy didn’t reciprocate in cookie exchange, but that this still doesn’t justify taking Eddie’s cookie without permission because – and here the teacher would have to give a second-grade level explanation of why this is wrong. For example: if everybody took whatever they thought they deserved, people would be taking from each other all the time, and there would be lots of fights. Or: how would you feel if you were Billy and somebody took your cookie without permission because he felt you owed it to him? Wouldn’t you feel that was wrong? Regardless of what he said, he would need to present an argument – which could be debated. Because that’s how moral reasoning works.

But he would also have to say: even if it feels unfair, Eddie has to suck it up, because the fact is that he, the teacher, gets to decide this question.

The point is: a debate about whether or not it’s wrong for Eddie to take Billy’s cookie is different in kind from a debate about whether or not Eddie actually took Billy’s cookie, and we need some kind of nomenclature for distinguishing the two questions. “Fact” versus “opinion” will do fine.

If there’s a problem here at all, it’s not with what constitutes a fact but with what constitutes an opinion – that is to say, a failure to distinguish between an opinion and a preference. For example: the statement “vanilla is the best flavor of ice cream” is an opinion. It’s also a stupid opinion because “best flavor of ice cream” is not really a thing. What the speaker really means is “I like vanilla ice cream best” or possibly “most people like vanilla ice cream best.” Either of those statements are statements of fact, not opinion – facts about individual preferences.

Now, what about “George Washington was the greatest American President?” That’s clearly a question of opinion, not fact, right? Ok – but is it a stupid opinion like “vanilla is the best flavor of ice cream?” The answer depends on whether a word like “greatest” has any social meaning. If it doesn’t – if we can’t reason together about what makes for greatness – then it’s a stupid opinion, because the only statements we can actually make are factual statements about personal preferences, our own or others’. But if it does – if we can reason together about what greatness means, its relationship to goodness, or to sheer historical importance – then it’s not a stupid opinion, because we can share it, debate it, and have our minds changed about it.

Which brings me to a final test proposition.

“There is no God but God, and Muhammad is His Prophet.” Fact? Or opinion?

Obviously, it’s a problem if you teach the above proposition as an example of fact. And if it isn’t a fact, then it’s an opinion. But if you were a pious Muslim parent, and learned that your child was taught that a central tenet of your religion was “just a matter of opinion,” you’d be unhappy, right? That statement is certainly more than a statement of fact about personal preference (“I like Islam best!”) – but it’s also not really something subject to public dispute, by which I don’t mean that such dispute is blasphemous or forbidden but that it’s a category error, at least within modernity, to argue with a proposition like the above in the way that you might argue about whether it was right or wrong for Eddie to take Billy’s cookie, or whether George Washington was the greatest President.

The statement, “There is no God but God, and Muhammad is His Prophet,” is a creedal statement, an affirmation. It’s something more forceful and substantial than a preference, not really subject to public reason like an opinion, and not subject to verification like a fact. It belongs in its own category of statements.

My question is whether McBrayer thinks moral truths belong in that same category. If so, then I would say that he is the one arguing against moral reasoning – arguing, in fact, that moral reasoning is impossible and that therefore what we need to teach children is obedience to moral commands. That view has a venerable history in Western and non-Western philosophy, but I dissent from it.

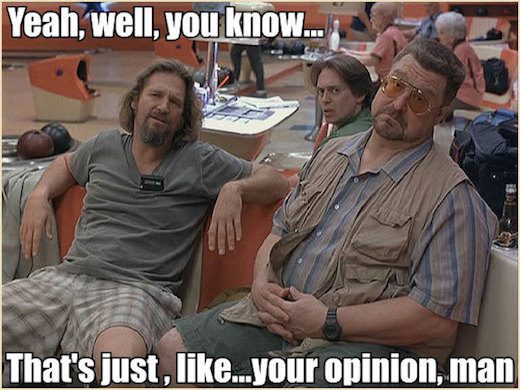

If he doesn’t think moral truths belong in that category, then I think he is just objecting to the specific words chosen by the Common Core, and not to the distinction itself. Because the distinction hanging over the bulletin board is entirely valid and even essential to moral reasoning. If it’s not being used that way, to promote the development of moral reasoning, but instead to wall us all off from each other with our indisputable personal preferences, the problem isn’t with the distinction itself, but with the fact (if it is the case) that we’re taking our view of opinion from Jeffrey Lebowski.

Comments