Majdanek: The Polish Death Camp

The summer after I graduated college in 1992, I spent several weeks wandering around Europe east of the Elbe, from Budapest, to Prague (I guess Prague is actually south of the Elbe, but whatever), and from there around Poland for three weeks before heading to Riga, St. Petersburg, Helsinki and Stockholm. While in Poland, I had the opportunity to visit a number of memorial sites related to the Nazi atrocities, including the Auschwitz-Birkenau complex and the site of the Majdanek concentration camp, near Lublin. When I visited them, it was soon enough after the fall of Communism that nothing much had changed about the way history was presented at the two camps. I don’t know how things have changed since, but I got a view of how the post-war Polish Communist government interpreted the crimes committed on Polish soil.

Auschwitz-Birkenau was the largest of the six extermination camps set up as part of Hitler’s campaign of mass-murder against Europe’s Jews, and the overwhelming majority of the victims there were Jewish (estimates are usually around 90%). But the memorial went out of its way to present the camp as the site of equal-opportunity murder, with pavilions for each of the various nationalities or ethnic groups represented among the victims. One for the Jews, one for the Belgians.

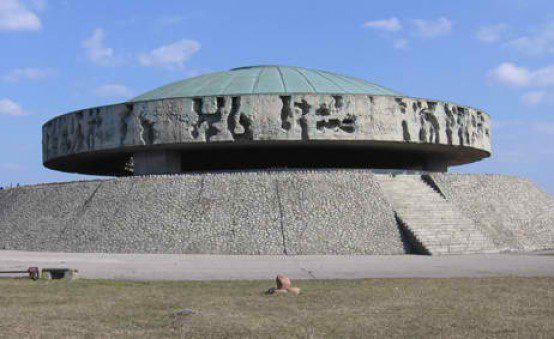

Majdanek, by contrast, was not originally conceived as an extermination camp, but rather as a slave labor camp (of which there were many across the Third Reich), and only later came to be used as a site for murder (though, needless to say, slave labor was itself frequently fatal). Majdanek’s prisoners included many Poles and Soviet POWs along with Jews, and though the Holocaust of the Jews was certainly part of the story (there was a plaque specifically commemorating the 18,000 Jews murdered on a single day in 1943), the site was presented as, effectively, the truly “Polish” death camp – that is to say, a place where Poles were gathered for extermination. And though most of those killed at the camp were probably Jews, those Jews were largely Polish (Auschwitz received Jewish deportees from all over Europe), and Jews may well have been a minority among the prisoners as a whole.

I found this attempt to nationalize the memorial at Majdanek a lot easier to take on the whole than the Auschwitz memorial’s attempt at universalism. Not much more accurate, but much easier to take. It felt less motivated by an effort to deny the obvious, and more by the entirely understandable human desire not to have one’s own suffering triaged out of consideration.

By contrast, I find the “Polish death camps” kerfuffle – Poles around the world (well, the ones that are addicted to the 24/7 news machine) bristling at the insensitivity of President Obama for referring to “Polish death camps” rather than “Nazi death camps in Poland” – a bit perplexing.

That’s not to say I don’t understand where they are coming from. I absolutely understand. If someone broke into my apartment to murder my neighbor, I wouldn’t be thrilled at having that crime known as “The Millman Murder.” And both Polish suffering and the Polish contribution to the allied fight against the Nazis have been sorely neglected by Americans in particular. And the Communist post-war government of Poland actively vilified the patriotic Polish nationalists in an effort to bolster their own legitimacy. So for a whole host of reasons, I understand why Poles bristle at the phrase, “Polish death camps.” They weren’t conceived by Poles. They weren’t run by Poles. And they weren’t intended primarily to kill ethnic Poles.

On the other hand, I’ve also heard a bit of griping from Jewish (and non-Jewish) observers of that Polish pique, saying, in effect: wait a minute, it’s not that simple. Polish resistance was substantial and real, and Poles lead the lists of individual saviors of individual Jews, but Polish collaboration in the Holocaust was also not incidental. And I understand where they are coming from as well – my maternal grandparents left Poland after the Kielce pogrom of 1946.

But I don’t like this reaction either, because I don’t think reciprocal demands for greater sensitivity get anybody anywhere. In particular, I don’t think throwing around words like “false and unjust phrases” encourages the pursuit of knowledge. Which is the only cure for “ignorance.”

The Nazis chose to commit many of their most heinous crimes on Polish soil, largely because the largest community of targeted victims was the community of Polish Jews, but also because Poland was also targeted for a more severe “renovation” into than was most of Europe – the Nazis aimed to destroy Polish society utterly and turn the Polish people into a slave caste, which isn’t what they planned for Denmark or Norway. The pressure of the Nazi yoke was much heavier in Poland than in most of the occupied countries, which meant that Polish resistance was more intense and extensive than in most countries, but also that Polish collaboration was more intense, and involved a far closer approach to the ultimate horror. [UPDATE: that was a poor choice of phrase, which I am very belatedly removing. I should have made clear that official Polish collaboration was almost nonexistent, in marked contrast to many other occupied countries – which reflected the unique place of Poland in Nazi Germany’s plans, as noted above. What I meant to refer to was the involvement of some Poles in running the death camps, the activities of szmalcownicy, and so forth. As should be clear from my larger point, I don’t consider those actions by individual Poles to be stains on the Polish national honor. I do consider them to be part of Polish history.]

And Polish anti-Semitism before the war was real, widespread, and had already prompted anti-Semitic legislation before the Nazi invasion. The Nazi occupiers exploited this feeling, as they did in other European countries, to better pursue their war of extermination against the Jewish people. Acknowledging that doesn’t make the Polish nation a co-bearer of war guilt. And acknowledging that doesn’t require asserting that anti-Semitism is wholly irrational, as opposed to being, in many cases, a rational but repugnant response to real problems (the difficulty in establishing strong institutions in a young nation with huge ethnic minorities, and the intense competition for resources of all kinds that characterized the inter-war period).

I am a firm believer in the study of history, which emphatically includes the history of the Holocaust. But I am a dissenter from the false religion of Holocaust worship. And this kind of extreme sensitivity to language, and to the drawing of sharp black lines is, I think, a part of that religion. If the Holocaust was not merely a crime of historic proportions, but a confrontation with evil unmasked, then anyone who did not see that evil for what it was, and resist it with all his or her power, was either a fool, or a coward, or a villain. But most people are none of these – and are not heroes either. We honor the heroes of that period – like the Pole President Obama was honoring when he made his faux pas – as of all periods, for doing something extraordinary. That honor implies, if it means anything, that most of us didn’t, and wouldn’t, measure up. If we had not measured up, then, we would have, in retrospect, been implicated. That’s just an unhappy truth about what the Nazis unleashed upon the world.

President Obama should, of course, apologize, and fire the idiot speechwriter who made this mistake, because diplomacy is diplomacy. But we who are not subject to diplomatic constraints should be free to say: the Nazi death camps are part of Polish history, and history, always and everywhere, resists our neat assignment of comfortable categories.

And now, I’m going to stop imitating Leon Wieseltier, and write about something else.

Comments