Hampton Roads and ‘Lincoln’s’ Secrets and Lies

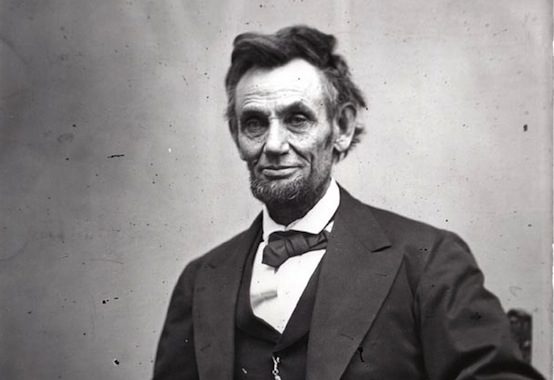

This past week, I finally got around to seeing Steven Spielberg’s film, “Lincoln,” which I was expecting to be bored and annoyed by (I don’t much like Spielberg when he’s being noble and serious), but wasn’t. Instead, during the movie I found myself carried along by the universally excellent performances (not only by Daniel Day Lewis but by a host of supporting players, most especially Sally Field as Mary Todd Lincoln) and, yes, by the general “uplift.” But from very early on in the film, something troubled me, a trouble that gnawed at more and more as the film wore on, and has dominated my thinking about the film since leaving the theatre. What troubled me is the same thing that I intuited might be the issue with “Zero Dark Thirty,” namely, that the imperatives of good dramatic storytelling drove the filmmakers to tell a more morally-problematic story than necessary.

“Lincoln” is the story of the passage of the 13th amendment to the Constitution, and a portrait of the character of President Lincoln as seen through the struggle to achieve this landmark reform. Right from the beginning, we are presented with the determination by the President to pass the amendment as swiftly as possible, before the new Congress is seated. Why does he need to move so swiftly? The incoming Congress, after all, will be even more Republican-dominated than the outgoing one. Well, according to the movie, as we learn from Lincoln’s gentle questioning of a pair of citizens who have arrived to petition for redress of a parochial grievance (there’s a dispute over who properly owns a toll in Missouri), a portion of the support for abolishing slavery derives from the conviction that abolition would hasten the end of the war, because, so they say, if the slavery issue were resolved then the South would have no reason to keep fighting. If, on the other hand, victory were achieved before passage of the amendment, then popular support for abolition might evaporate.

The first half of this isn’t problematic. The historical record shows that Lincoln believed that abolition would strengthen the Union position and demoralize the South, and for this reason the Republicans had been preparing the ground for the amendment since 1863. The state of Nevada was created in 1864 in order to assure there were enough states to ratify abolition. Maryland abolished slavery in 1864. And, of course, Lincoln won reelection in 1864 on a platform of unconditional surrender and abolition. All this is before the events of the movie. It seems to me that the reason why Lincoln believed abolition would demoralize the South is that it would reveal how united the North was in its aims. The South would therefore despair of convincing the North to agree to a negotiated peace, and would therefore agree to unconditional surrender rather than continue to fight with a view to getting somewhat more favorable terms.

The idea, though, that the country would simply turn its back on abolition if it achieved total victory on the battlefield seems strange. After all, in reality after victory the Republican Party not only didn’t retreat but advanced further down the road of racial equality, passing the 14th and 15th amendments. So why this plot point suggesting that Lincoln had to pass the amendment in early 1865, or the cause of abolition might be lost? Why, after moving slowly but steadily in a more radical direction over the course of the war, does Spielberg’s Lincoln suddenly fear delay?

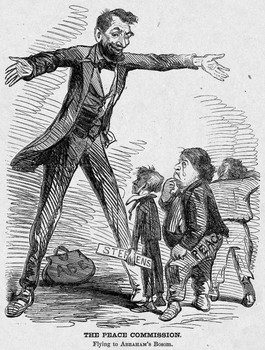

Although it doesn’t entirely make sense, this plot point is crucial to the story because it generates urgency, a ticking clock. And to ratchet up the tension and create a “turning point” moment, the President is shown manipulating the clock. He agrees to receive a peace delegation to win the votes of conservative Republicans for the amendment, but he delays that delegation’s arrival in Washington so as to prevent the prospect of peace from draining support for his amendment. The crucial “long dark night of the soul” scene is the one where President Lincoln revises a message to General Grant, from originally telling him to escort the commissioners to Washington to telling him not to do so, because, in the end, the war must be about ending slavery. The President then tries to keep the commission a secret and, when word leaks out and threatens to scuttle the vote on the 13th amendment, he frames a lawyerly response to suggest that there is no peace commission, when in fact there is, without actually lying. (The peace commission is outside the city, and the President says there is no commission “in the city, nor is there likely to be.”)

Again, the details about the President’s lawyerly evasion are accurate, but the context of the actual peace negotiations (and I strongly encourage clicking through to that particular link) was quite different. Rather than debating whether it was worth continuing the war to end the scourge of slavery or seek peace immediately, the President was always determined both to seek peace and to achieve emancipation. The variables in play were the pace of emancipation, the nature and amount of compensation to slaveowners, the leniency to be shown towards those who took up arms against the government – and on all of these, the President was prepared to be very magnanimous (among other things, because he recognized slavery as a stain on the national honor, and not merely a sectional problem). But from the beginning, the biggest non-negotiable was an unwillingness to recognize the CSA as a legitimate government in any way.

(Which, by the way, was the real moral question of the war from the Northern side: whether war to preserve the Union was legally and morally right, or whether it wouldn’t have been better for Washington to negotiate a severing of ties with the Slave Power rather than fight to bring it to heel. The South was fighting to achieve independence, and they sought independence in order to preserve slavery. I have no patience for pro-Confederate revisionism because this truth is unavoidable, but must be avoided to make the moral case for secession. The North, by contrast, was fighting to keep the South in the Union against the South’s will. The justice of that fight will remain a great question to debate. I happen to think the Unionists have the better part of that argument – but I recognize that there’s another side.)

It was this question of whether receiving the commissioners would constitute recognition that resulted in a brief hold-up, and not concern about passage of the 13th amendment. And while the President recognized that it was advantageous to get the amendment passed by the outgoing Congress, he knew that the incoming Congress was even more likely to pass it. The true stakes with the vote, in other words, and with the President’s lawyerly denial of the commission’s presence in the city, were not especially high. And the true stakes of the peace commission related to the conduct of the war. Handling it well, as Lincoln did, would unite the North more firmly behind the war effort, and demoralize and divide the South. Handling it poorly could have done the opposite, prolonging the conflict even further, and even further embittering the aftermath.

Departing from the historical record in this way is fine on one level – “Lincoln” isn’t a documentary. But what might appear to be mere changes in emphasis actually have broad implications that should be disturbing.

If President Lincoln was selling the 13th amendment as a war measure, but in fact believed the opposite – that peace was potentially at hand, and if it came prematurely it would scuttle the prospects for abolition – and actively hid the prospects of peace from Congress and the people in order to ensure his goal of abolition, even at the potential price of a prolonged war, then the President, regardless of whether he actually lied, deceived the nation on a fundamental question of war and peace to achieve a moral aim: the end of slavery. And you have a big movie moment – that scene with the telegraph operators where Lincoln changes his mind about receiving the commissioners. But if, as was in fact the case, it was unlikely peace was at hand, but the President was going out on a limb to try to see whether there were any prospects for peace on terms his party could accept and, if not, to set the terms of the end-game most favorably to his side; and if the timing of the passage of the 13th amendment was helpful but not essential either to the cause of abolition or to the conclusion of the war; then the President’s lawyerly deception of Congress during the vote on the amendment was just clever politics. But, unfortunately, if you embrace this reality, the tension drains out of your movie.

I don’t want to overdo my point. I’m not saying that “Lincoln” is “bad history,” or that you shouldn’t see it. Among other things, it prompted me to take a look into half-remembered or previously unread books and articles about the period to see if I was remembering my history right. But it’s telling that I’ve read so much in the press about the revelation that President Lincoln engaged in routine corruption to grease the wheels of legislation (which is certainly true, and important to understanding how politics worked before civil service reform) and so little about the ways in which the movie implicitly treats deception in questions of war and peace. We may have become more scrupulous about the former, and more cynical about the latter, with the passage of time. I’m not convinced that speaks well of us.

(A final aside: would Lincoln have considered backing out of his repeated promise, and the promise of his 1864 platform, to abolish slavery in order to achieve peace, even as late as 1865? I doubt it. The principal source for the claim that President Lincoln considered backing down on emancipation is Confederate Vice President Stephens, who claimed the President said at Hampton Roads that the Emancipation Proclamation would no longer be operative if hostilities ceased. Lincoln also advised the Southern states to voluntarily and prospectively ratify the 13th amendment, pursuant to rejoining the Union, but, according to Stephens, did not demand abolition as a condition of surrender. Needless to say, his account is disputed, among other things because it contradicts numerous public statements by the President to the contrary, not to mention his party’s platform, not to mention the fact that he had just shepherded the 13th amendment through the House. Since the Southern states demanded recognition of their independence at Hampton Roads, all this negotiation was beside the point, so I tend to agree with David Herbert Donald that whatever Lincoln said at Hampton Roads was intended to undermine the CSA’s morale and encourage unconditional surrender, and that there was no actual possibility of abolition being abandoned as a war aim.)

Comments