Half Past Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil

Last month, not having yet seen the movie, I wrote the following regarding “Zero Dark Thirty” and its depiction of torture:

A good story typically has a clear arc, with either a comic or a tragic ending. In a well-told story with a comic arc, discordant notes that cut against the comic grain can serve any number of specific purposes, but if the story holds together those purposes will ultimately be subordinated to the overall arc of the story. A hero may have profound flaws – but those flaws actually make us like him even more, because they humanize him. If the flaws are integral enough to the hero’s personality, the heroic arc of the story may even appear to justify those flaws. And people who pride themselves on their taste and sophistication are particularly likely to prefer stories with “complex” and “flawed” heroes over the kinds of stories where the hero, as part of her journey, “overcomes” or “triumphs over” her flaws.

In this case, the ending is comic – the hunt for Bin Laden is successful. The filmmakers were committed to writing a serious and complex story, though, not a patriotic fable. They wanted to show the “dark side” of the war on terror. But what is the function of that “dark side” in the story? Well, there are only so many choices.

The dark side could be the preserve of cardboard villains – people who have no genuine patriotic motives, or who, even if they are well-intentioned, need to be explicitly overcome in order for the hero (America) to achieve its goal (hunting down Bin Laden). But this would make for an emotionally simpler story, a fictional world in which the good things all go together – we can achieve our goal without compromising our morals. That probably wouldn’t have satisfied the filmmakers.

Alternatively, the dark side could be shown to be integral to victory. Without torture, we’d never have gotten Bin Laden. That’s the kind of message that comes across from the television show, “24,” that routinely shows torture to be effective. That’s what some people are accusing “Zero Dark Thirty” of doing, but I doubt that’s the case, because this is another kind of simplified storytelling – this is the easy kind of “hard truth” that some people find emotionally reassuring in times of crisis. I found a version of it reassuring myself in times past.

The third, most sophisticated way to use the “dark side” is as counterpoint. So: it’s not that we had to banish the dark side to win, nor is it that the dark side was necessary to victory, but that the dark side is just that: the dark side. An unpleasant side effect of an effort that, overall, was just and worthy. We didn’t need to torture in order to get Bin Laden. But it was, on some level, predictable that we would torture.

I suspect this is what Bigelow and Mark Boal, the screenwriter, were after. But the thing is, if the comic thrust of the story is clear enough (comic in the sense of having an upbeat ending, not in the sense of being amusing), the story itself is going to produce a great deal of pressure to justify the dark side. If the quest itself was necessary and just, and the dark side, while neither necessary nor just in and of itself was an inevitable consequence of the quest, then, we will conclude, it was, in some sense, justified. Because the only way to be sure to avoid it was not to go on the just and necessary quest.

Well, now I’ve finally seen the film, and while I stand by most of this, I have to modify my conclusions in certain ways. Torture is more integral to the story than I realized. And it is less clear than I thought that this is a comic narrative arc, one with an “up” ending that allows us to understand all that came before as necessary to this positive conclusion.

If you come into the film with the assumption that the hunt for bin Laden was just, righteous and necessary, and that America is the hero, then I’m afraid I think it’s very likely that the film is going to make you think more positively about torture than you may have going in. Four reasons. First, there is no “evil torturer” character – a genuine sadist who delights in causing pain and humiliation. Second, there is not a single person who expresses any concerns about torture other than political ones. Third, there is nobody who is tortured who is subsequently discovered to have been innocent. Fourth, there is no evidence that torture has resulted in false leads. If you take out all of those elements in the case against torture, there’s not much of a case left.

I’m inclined to applaud the film for avoiding the “evil torturer” character, because his presence could make it easier for a pro-American audience to conclude that torture was a problem of personnel rather than policy. But the fact is that part of the case against torture is that a torture regime empowers sadists. And no character in “ZDT” fits that description. Some critics have advanced Dan (Jason Clarke) as a candidate for the position, but the shoe won’t fit. Dan hates the terrorists he’s interrogating, and he seems to have gotten comfortable with torture – and he emphatically believes in it. (When his boss demands somebody to talk to Congress, he volunteers – “I ran the program; I’ll defend it.”) He’s politically savvy enough to want to get out before the politics change decisively, but he’s also just sick of years of this kind of work. No way this is our “evil torturer” character.

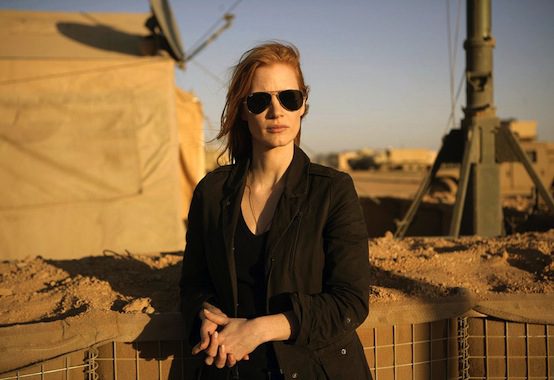

And nobody else thinks he is either. Down the line, top to bottom, nobody ever says anything critical about the torture of prisoners. Multiple times, after torture ceases, CIA officers complain that they can’t get good information anymore now that they can’t torture suspects. Nobody contradicts them. Maya (Jessica Chastain), the heroine, participates in the torture of the first prisoner we meet, pores over the records of prisoners who have been tortured looking for useful information, and threatens prisoners in order to get them to talk (specifically, there’s a prisoner threatened with being sent to Israel – he talks, saying he has no wish to be tortured again). The fact that the CIA – the organization we’re counting on to get bin Laden – is clearly, overwhelmingly in favor of torture from start to finish, and never changes its collective mind about this, doesn’t mean the movie is endorsing that view. But it does mean that the audience has nobody to latch onto as presenting a counter-narrative.

This is not a movie “about” torture, so it probably makes sense that there’s no foray into the question of innocence. After all, why would a CIA operative worry about that? The police have to concern themselves with protecting the innocent because that’s their job. The CIA’s job is getting intelligence. But the fact that there are no false leads that come out of torture is harder to explain. There are false leads – most prominently, the false promise of a “Jordanian mole” that winds up getting a whole bunch of CIA personnel killed in a suicide bombing. But that lead is planted by the enemy. And while we see how torture can reduce a prisoner to incoherence, unable to offer any useful information at all, even this has an upside. Because he’s been broken, he doesn’t remember what he’s already said. So Maya can bluff him into giving her information in a subsequent interview over lunch. Even when torture fails at first, it can ultimately succeed, if combined with clever interrogation skills.

Much has been made of the fact that, halfway through the film, they still haven’t gotten any closer to finding bin Laden. Maya’s main lead – Abu Ahmed, the nom-de-guerre extracted from Ammar (Reda Kateb), the first tortured prisoner we meet – has gone cold; she thinks he’s dead. They have nothing – the whole program of torture has gotten them nothing, and now they don’t even have that. And then, they get a lucky break: information in the files, from right after 9-11, reveals that Abu Ahmed isn’t dead; they’ve been using the wrong photo, a photo of his brother. This detail was missed because, as they say early on, they’ve been looking for a needle in a haystack – they got a huge dump of leads right after 9-11, from a zillion different friendly sources, and had no way to make sense of it all. So they didn’t need to torture – the answer was in their files all along.

Except, the only reason Maya knows that piece of information is important is that she’s already spent years obsessed with finding Abu Ahmed. And the reason she’s done that is that she got that tidbit from a detainee. That’s how she knows it’s a needle and not a piece of hay.

If you come into the movie absolutely sure of your opposition to torture on both moral and practical grounds, then what this movie shows is that the United States of America engaged in torture; did so systematically; and did so with the full support of the intelligence community and with authorization from the highest authorities. And it shows that the people who constructed that policy remain not only unrepentant but convinced of the policy’s importance. As such, you will probably come away thinking, “wow – it really wasn’t just a few bad apples; we were really committed to this stuff. That’s bad.”

But: if you come into the movie absolutely sure that America was righteous in doing whatever was necessary to get bin Laden, then what this movie shows is that key intelligence came from tortured prisoners; that overwhelmingly the intelligence community thought, and still thinks, that torture was necessary; and that opponents of that policy – up to the current President – had political concerns uppermost in their minds. (There is a clip of the President saying “we do not torture” and explaining that he aims to make sure we don’t so as to “restore our moral standing” – that is to say, to improve our image, which is a political concern.) As such, you will probably come away thinking, “gosh, the CIA was right – torture was necessary.”

So what do the filmmakers want us to think?

On the one hand, I’m inclined to think they don’t care. They are presenting a bunch of people doing their job, most of them with half an eye on the job and half an eye on office politics, and one of them – Maya – absolutely focused on the job (and her own particular lead). They want you, the audience, to feel what it might really have been like to be on that job, in a more visceral and immediate way than journalism could. But, in a journalistic fashion, they are avoiding giving an independent perspective on the events. They aren’t telling you whether the CIA are the good guys are the bad guys. They are just telling you that they tortured people as part of the effort to get bin Laden, and they aren’t ashamed of that, and they ultimately got him. You decide the balance.

But I don’t think that’s entirely true. Listen to the underscoring of the last half hour of the movie. It’s doomy and anxious as the stealth helicopters rise up and head into Pakistan. It stays that way all through the assault on bin Laden’s compound. That assault, by the way, is resolutely unromantic – but, again, that dovetails with the “journalistic” approach I talked about. But the camera lingers on discordant elements – the growing crowd of curious and angry Pakistani onlookers, the anxiety of the SEALS who know they have to get out efficiently, and, most notably, the Hakim (Fares Fares), an intelligence operative on the team who’s clearly a native of some sort, and who seems particularly affected by the carnage in the compound (dead bodies, screaming women and children), and the potential for worse carnage if the crowd outside doesn’t disperse. And then, with a pause to blow up the disabled helicopter, we’re headed home – and yet we’ve still got the doomy underscoring. There’s no triumphalism. Indeed, if you blinked you might have missed that the mission is accomplished, that bin Laden is dead, that the “good guys” won. And that underscoring carries through to the big final question on which the movie ends: where do you want to go now?

I don’t think that adds up to “we report; you decide.” Katheryn Bigelow is actively undermining the “natural” mood of an American audience when they see bin Laden get shot. She’s saying: this, in and of itself, is just another assassination. If it means anything, that meaning comes from context. But the context she provides is ominous rather than triumphant.

That final question is asked of Maya, the gal who got bin Laden. And, rather than answer it, Maya tears up. What is she thinking? Normally, we’d have some basis of answering based on Maya’s character. But Maya, though she is supposed to be based on a real character, doesn’t have a character – not in the sense of a personal history or backstory. She has no friends. She has no interests. But she’s not just a monomaniacal person – we’ve met those types before in movies. She is her monomania. There isn’t anything else to her.

There’s a scene, not long before the go-ahead is given for her operation, where CIA chief Leon Panetta (James Gandolfini) sits down with Maya in the CIA cafeteria for a little chat. He wants to get a read on her, because he realizes that to the extent that anybody supports the idea of a mission to Abbottabad to get bin Laden, it’s because she is so convinced bin Laden is there – there’s very little confirmatory evidence. (Multiple characters compare the intelligence unfavorably to the intelligence on WMD prior to the Iraq War.) But she is absolutely certain. How does he weigh that without knowing anything about her?

So he sits down with her, and asks her: how long have you been with the agency? Twelve years. What have you worked on besides bin Laden? Nothing – I was recruited right out of high school. And why do you think we did that? Maya answers something like “I don’t think I’m allowed to answer that.” It’s a weird answer – I’m sure there’s some technical reason that I don’t know that explains why she can’t tell any personal information to her own boss, but I don’t know what that reason is and the movie doesn’t give it to us. All we get from the movie is a big black underscore: we know we haven’t told you anything about this woman, anything to explain why she’s so monomaniacal, anything to explain why she’s right and everybody else is wrong, anything to make her an individual. We know that. We’re not going to give you that. She’s just Maya.

Which leaves Maya, in my view, as more symbol than character. She is the embodiment of our own national demand for retribution. She is the force that commanded: we’re not stopping until we get the guy who murdered 3,000 innocents in cold blood on September 11, 2001. We’ll do whatever it takes. Nothing else really matters.

That’s what this movie is about. It’s a movie about that demand, that force, that virtually all of us felt, and that transformed, for a while at least, possibly permanently in some ways, our relationship to much of the world, to the national security state, to our sense of morality. That force is real, and we are protective of it, and now that it has done its work we don’t know where to go, nor precisely what to make of the work that it did, through us.

As a work of narrative art, “Zero Dark Thirty” has its limitations. I tend to be drawn to stories with strong characters, and there are no strong characters in “ZDT” because every character is comprehensively subordinated to the question of what their place is relative to this single question, the hunt for bin Laden. As a work of history, it has even more serious limitations. Just for starters, the only mention of the Iraq War is of WMD as something the intelligence community got wrong – how that war impacted the effort to defeat al Qaeda is left completely out of the narrative. But as a portrait of America and its urgent need for retribution that dominated the national psyche in the post-9-11 years, “Zero Dark Thirty” is valuable, because it is a portrait of exactly that, and nothing much else.

Don’t go to this movie to learn whether torture was necessary or not to get bin Laden. Go to this movie to understand why we – not just the Bush Administration or the CIA, but much of America – embraced torture. We did it because that’s what Maya, who only worked on getting bin Laden and nothing else, would have done.

Comments