Double Feature Feature: The Demands of Justice

I recently saw the heart-warming and heart-rending movie, “Fruitvale Station,” and it got me thinking about what the demand for “justice” in terrible circumstances like this actually means.

For those who are unfamiliar with the movie: it is based on the story of Oscar Grant, who was shot in the back by a police officer on the platform of the Fruitvale Station of the Bay Area Rapid Transit. Grant had been involved in an altercation on the train, was in the process of being arrested, and was lying on the ground when he was shot. The film beings with cell phone footage of the actual arrest and shooting, and then circles back to the morning of the previous day to show us the last day in the young man’s life (he was killed at the age of 22).

The movie is heart-warming and heart-breaking simultaneously for a single reason: because the filmmaker, Ryan Coogler, does a very good job of giving us a rounded portrait of the young man about to die (played with great sincerity by Michael B. Jordan). He is sweet, loving to his daughter, devoted to his mother (Octavia Spencer, playing more of a type), friendly to strangers who need to pick out fish to fry or whose pregnant wives desperately need a restroom on New Year’s Eve. And he’s hot-tempered, roughly grabbing the arm of his former boss when he won’t give him his job back (and, fatally, unable to stop himself from arguing with the cops on that platform); irresponsible – he lost the job for chronic lateness, not to mention he’s recently cheated on the mother of his beloved daughter for no particular reason than the opportunity presented itself; and generally childish in his approach to the world (as his girlfriend recognizes to her dismay).

It’s heartwarming to see such good portraiture, and to see a world in which the overwhelming majority of people Oscar interacts with – white and black – affirmatively wish him well, as he does them. You can’t watch how this young man goes through his day and think, “the world was just out to get him.” Even the sun shines on him kindly.

And so it’s heartbreaking even if we forget that he is about to die, because there is no reason to believe that this charming man’s life would turn out well anyway. He makes a decision at one point to stop dealing drugs – even tosses the remainder of his marijuana supply – but he has no other obvious means of support, and he doesn’t show any signs of finding one. How likely is he to stick with that resolution? With two strikes already on his record, and a temperament like his, he was likely headed for a slower-motion tragedy of a lengthy prison term even if he managed to dodge the bullet we already know had his name on it. The filmmaker may want me to forget that – or to believe in the transformative power of New Year’s resolutions – but the actual film, and Jordan’s performance, won’t let me.

His death at the hands of the police, as portrayed, is partly a consequence of one officer’s unprofessionalism. Officer Caruso (played by Kevin Durand) is gratuitously abusive, which does nothing to give him control over the situation (presumably his goal), but instead inflames everybody’s emotions. And it’s partly a consequence of Grant’s own foolishness in repeatedly arguing with the cops and disobeying their orders to sit down and shut up – never a great idea, and especially not a great idea when the cops in question are already riled up and suspect you of being dangerous because they got a call about an altercation. (Incidentally, the altercation starts because Grant is jumped by an old enemy from prison who happens to be on the same train.)

But Caruso isn’t the one who shoots Grant; it’s another officer, who hasn’t been shouting insults or doing much of anything. The movie, in other words, pretty much endorses the verdict of the officer’s trial: that he killed Grant by mistake, not out of animus. (The officer claimed he mistook his pistol for his taser. He was convicted of involuntary manslaughter and sentenced to two years.) A significant portion of the blame for the tragedy accrues to chance and inexperience – factors that cut against talk about injustice.

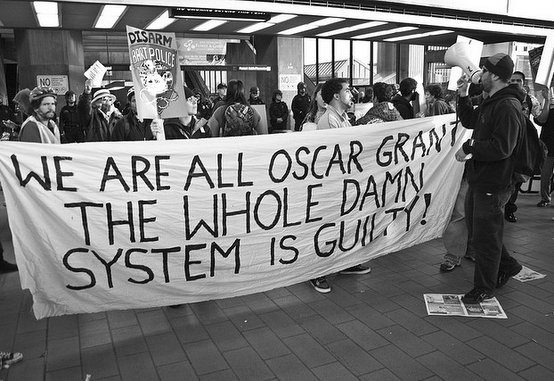

And yet that’s the note – a demand for justice – on which the movie ends. And understandably so: a young man lost his life for no good reason, and we see that it was, if not inevitable, all too predictable, all too likely. That’s not just, is it?

So what would be?

Our system of justice, criminal and civil, is organized around the principle of assigning fault. If in an adversarial contest – a trial – the state can convince a jury that you have broken the law, beyond a reasonable doubt, then you are convicted and punished by the state. If in a similar contest, a plaintiff can convince a judge or jury that you are liable for your actions to a certain degree, you will be compelled to pay damages. We assess fault, and either punish or compel recompense.

But does that satisfy our demands for justice? Maybe. But often, I think, not. What would satisfy better? If the officer who killed Grant were convicted of murder, would that have been more just? Some might think so – but the motivation is probably the old “eye for an eye” instinct. A young man was killed for no good reason. Doesn’t his blood cry out? If we identify with the young man – if he’s one of “ours” – then we don’t want to hear that the killer didn’t mean it. Since we can’t get the young man back, want compensatory suffering imposed upon the “other.”

Would a larger monetary settlement satisfy? It’s hard to see how. The value of Grant’s life doesn’t primarily inhere in his monetary value. Inasmuch as a larger civil victory would satisfy, it would be because it would feel like victory – a largely symbolic victory, but still.

What about reforms of some sort – more training for the police department or something? The narrative we are shown doesn’t offer much encouragement of the idea that this would be effective – tasers themselves, after all, were originally added to the arsenal as an alternative to potentially deadly force.

The search for justice in an adversarial system like our own is, in fact, not very likely to prove satisfying. That’s the point of a very different movie about a pointless death – “Margaret,” written and directed by Kenneth Lonergan (which came out, after a lengthy delay due to editing problems, in 2011), which also has a young and irresponsible but winning protagonist with a childlike approach to the world at its heart, in this case Lisa Cohen, a rich New York teenager played by Ana Paquin; and like “Fruitvale Station,” “Margaret” is interesting primarily for that excellent central performance.

“Margaret” begins with an accident. A bus runs a red light, and kills a pedestrian in the crosswalk. But to call it an accident is incomplete. The bus driver (played by Mark Ruffalo) ran the light because he wasn’t watching the road. But he wasn’t watching the road because he was distracted by Lisa – who was trying to get his attention to ask him where he got his cowboy hat. (She wants the hat because she’s soon to go on a vacation to a dude ranch.) When the accident happens, Lisa rushes to the side of the injured woman, whose leg has been severed, and tries to comfort her while other bystanders call 911 and try to apply a tourniquet. The woman dies in Lisa’s arms.

What follows for the rest of the movie is Lisa’s attempt to assuage her sense of guilt at her responsibility for the accident. First, she lies to the police investigators and says that the bus went through a green light. She does this partly because she feels for the bus driver, who makes eye contact with her as they are both being questioned, and clearly fears losing his job, but more because she knows that she was trying to distract him, and that therefore, properly, much of the blame is really hers.

As time goes by, she acts out more and more – getting into nasty political arguments in Social Studies class, fighting with her mother, an actress (played by J. Smith-Cameron), engaging in risky sexual behavior (including seducing a favored teacher, played by Matt Damon), and so forth. She needs some way to assuage her guilt – and finds it by launching a crusade to get the bus driver fired. She contacts the dead woman’s best friend, tells her that she lied to the police, and plots with her to sue the MTA. She also goes to the police to recant her statement, and confronts the bus driver in his home.

All this activity proves decidedly ineffectual if the goal is justice. The suit goes forward, and the MTA offers to settle for a nice sum (it turns out the driver had a record of prior accidents, but was not dismissed). The beneficiary will be the next of kin – a cousin in Arizona who barely knows the dead woman. The bus driver will not be fired, because that would imply an admission of guilt on the MTA’s part. Lisa finally breaks down in the lawyer’s office, screaming that all she wanted was for the bus driver to admit he was at fault, for someone to admit it, because she’s at fault and she can’t just live with the idea that nobody is ever going to be punished for what happened. But that’s precisely what she has to live with.

In spite of the very strong performance by Paquin, and the generally strong writing on a scene-by-scene basis, the movie is unsatisfying. Partly that’s because of inconsistent pacing. Partly its because the world we are shown is a world as a teenager sees it – a self-involved teenager who really thinks everyone is a phony out to get her. Whereas in the world of “Fruitvale Station” nearly everybody, with rare exceptions, basically wishes each other well, in the world of “Margaret” everyone, with rare exceptions, is utterly self-involved, to the point of not even registering other people’s emotions. I was genuinely shocked by how little Lisa’s mother and father (the parents are divorced) do to help her cope with her trauma, how little they even try to communicate. Nearly every interaction between people in this film is characterized by irritation if not outright hostility; I felt like I was inside a Raymond Carver story.

But another reason is that, thematically, the film aims to show us the inherently unsatisfying nature of the search for justice. Trials, being inherently theatrical events, are tailor-made for cinema. But very little of what goes on in our justice system actually takes place at a trial; trials rarely result in the kind of total victory and the defeat of outright malefaction that we associate with “justice” in cinema; and what a trial really results in is victory for one side or the other in an adversarial system. It is the result of the system as a whole that we hope approximates justice, and what we mean by that is no clearer to us than it was to Socrates’s interlocutors.

In the most fundamental sense, justice means a restoration of order. In a harmonious community, where order is communally maintained rather than imposed by force, that necessarily means satisfying the community, so it can go back to doing its job of maintaining order with equanimity. Justice, in other words, is inherently a matter of communal perception, and not an objective quality.

This is the conception that underlies the idea of restorative justice. Restorative justice is usually discussed in terms of alternatives to punishment, but the heart of the concept doesn’t relate so much to what consequences the offender faces as how those consequences are agreed upon. The assumption is that victim and offender are both parts of an organic community, and that the integrity of that community has been violated by the offense. Restoration isn’t achieved unless the victim feels the offender and community have done what is necessary to heal the breach – and unless the offender has been reintegrated into the community through his reparative actions.

What Lisa Cohen wanted, needed, was some kind of restorative process. One senses she would eagerly have been “punished” by such a process, in the sense that she would have accepted responsibility and mandatory action of one sort or another to make up for her responsibility under such a process, that it would be therapeutic for her in a way that processing her guilt, either alone or with some kind of professional counsellor, could not be, and that pursuing “justice” via the courts wasn’t either (and wouldn’t have been even if the bus driver had been fired).

Such a conception of justice is not a practical one for a large commercial society. But I think it accords much more closely with what we actually want when we seek justice. The demand for victory that we associate with the adversarial process presumes, in a sense, the non-existence of this integral community. No wonder it rarely satisfies.

And it is a viable approach to political language in cases where it may not be viable as an approach to criminal justice. We debate cases like Oscar Grant’s – or Trayvon Martin’s – largely in terms of culpability and liability, we are avoiding the real reason why there is a cry for justice. The injustice is that a young man died for no good reason. It is our adversarial system of justice that demands we respond either with: it is this one’s fault, and he will be punished, or it is not, and nobody will be punished. But our communal response is not limited to that dichotomy, and we impoverish our response when we limit our language to the kind of language that a court would accept.

Sadly, I fear we are more likely to take a work that uses just that kind of richer language – a movie like “Fruitvale Station,” for example – and either subject it to an inquisitorial process designed to determine if it is “fair” in its depiction of the various parties, or to hold it up as an indictment of “the system” for injustice, as if we all knew what its opposite looked like.

Comments