Antic Hay: Noël Coward’s Hay Fever at the Stratford Festival of Canada

After taking in last year’s excellent Blithe Spirit at the Stratford Festival, I argued that Coward’s play anticipated Seinfeld in its characters’ utter self-involvement and the play’s fundamental misanthropy. Well, the director of this year’s Coward, Alisa Palmer, seems to have been of the same mind about her play: “Hay Fever reminds me of Seinfeld, a show whose creators, like Coward, pre-empted their own critics by declaring, cheekily, that their show was ‘about nothing.'”

I should be delighted that we agree, but, you know, I’ve got my critic hat on. And the thing is, generally nothing will come of nothing. Palmer’s production comes perilously close to proving the truth of Lear’s statement, though the play is redeemed by certain key performances.

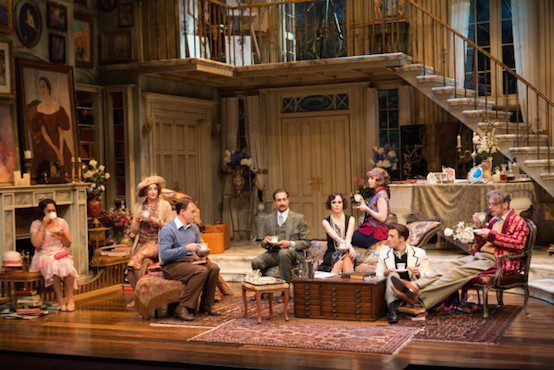

Hay Fever‘s plot (which Coward himself admitted was minimal to the point of near-nonexistence) revolves around the by-now well-worn scenario of throwing a bunch of squares and a bunch of cool, artistic types into close proximity. Judith Bliss (Lucy Peacock), retired stage actress, her children, Sorel (Ruby Joy) and Simon (Tyrone Savage), and her novelist husband, David (Kevin Bundy), have each, unbeknownst to the others, invited a romantic prospect down for the weekend. They are each appalled by having their respective plans upset by the others, and respond by treating each other’s guests with outrageous rudeness.

Over the course of the first evening, the opening pairings, which are obviously mis-matched in terms of both age and temperament, get more-plausibly recombined. These recombinations prompt Judith to bouts of extreme theatrical excess in which her family, knowing the routine, join her, to their guests’ distinct alarm. Not so much Blissed-out as simply exhausted, the invitees decamp collectively first thing the next morning, leaving their hosts to comment on their rudeness, and resume their normal, quarrelsome family life.

The play could be read as a satire on the artistic sensibility – or, alternatively, as a satire on the lack of sensibility of the squares – or both, something like the movie, “Impromptu.” But Coward isn’t engaged in social satire, because satire requires an affirmative set of values against which a society may be judged. Hay Fever has no such values – it’s blissfully relativistic. Instead of values, it has manners. But nobody agrees what those manners ought to be – and it is here where the play approaches the Seinfeldian.

It’s significant that what characters on all sides of Hay Fever are primarily concerned with is the rudeness of the other characters, a rudeness that can be manifested by too little attention or too much or simply the very wrong kind. Seinfeld‘s plots frequently revolve around characters asserting or violating norms of behavior, and engaging in wild theatrics around the necessity of upholding said norms, notwithstanding that said norms are invariably completely spurious. The Bliss family inhabit a somewhat similar world, inasmuch as they, by virtue of their position as artists, have a kind of professional responsibility to be able to play all sides, emotionally, in a scene, and hence can’t take any of them seriously. Each member of the family plays this out a bit differently; the novelist likes to see things as they really are, and then pretend that they are otherwise, while the actress dives right in without bothering to discern whether there is a reality of any kind at question. But it amounts to much the same thing either way: they all believe that sincerity is the key thing in art; once you can fake that, you can fake anything.

That’s what I see in the play, at any rate. To realize that vision requires giving each visitor to the Bliss household a distinct integrity, a vision of how one ought to behave, that will be upended by the Blisses. The only character who I saw manifesting such a vision was Sanjay Talwar’s professional diplomatist, Richard, and it’s not an accident I think that Talwar’s touching performance gets the most heart-felt laughs of the night. (It’s also not an accident, I think, that the diplomatist is the only character definitively to transgress against propriety, in making a pass at the married Judith Bliss.) Gareth Potter’s bluff boxer, Sandy, is perfectly plausible, as is Cynthia Dale’s predatory minx, Myra. But they don’t come into sufficiently sharp focus; we don’t see clearly how their respective senses of the way people ought to behave is disturbed by the ways in which the Blisses transgress. (Dale, in particular, seems more put out that she isn’t getting over than furious that David has already read – indeed, written, many times – the script she’s reading from as she tries to seduce him.)

Something’s off on the Bliss side of the fence as well, though Peacock’s antics never failed to bring a smile to my face, and Bundy got at the heart of the matter in his scene with Dale. I have a sneaking suspicion that Palmer harbors sentimental feelings for their family, and that she’s directed them to play big even when they aren’t formally “playing” a role so that we’ll get that these are lovable eccentrics, and fall for them as she has. But if she has sentimentalized them, it must be because they are artists, like she is. And the thing to remember about the Blisses is that they aren’t really great artists – they aren’t even really that good. They’re successful pros; that’s all. The play Judith loved doing so much sounds ghastly – her children tell her it’s ghastly, and even she knows it’s ghastly. But it was a great role because it gave her so much scenery for her to chew. David has no pretensions to greatness; he’s a hack novelist and he knows he’s a hack novelist. There is no Chopin here, no Delacroix.

Coward is honest enough to see the Blisses’ eccentric manners as tribal markers rather than signs of any higher calling. But if that’s all they are, then this can’t be a story about hapless squares running afoul of charmingly outrageous artists. Which is a good thing, actually, because that particular story just isn’t terribly funny, and no amount of “amping up” of the acting nor layering-on of slapstick will really make it so.

Hay Fever plays through October 11th at Stratford’s Avon Theatre.

Comments