My Cassandra Problem — And Ours

Once again, I strongly urge readers to sign up for Aaron Renn’s e-mail newsletter, The Masculinist. Whether or not you agree with his take on the intersections of culture, religion, and masculinity, Renn is asking some of the most important questions of our time. You find things in The Masculinist that you don’t get elsewhere. Read back issues and subscribe here.

A year ago, Renn wrote in Mere Orthodoxy about the Jordan Peterson phenomenon. He said that Peterson’s advice to his audiences is pretty banal (e.g., “Clean your room,” “Stand up straight with your shoulders back”), but this is why Peterson has become such a big deal:

It’s not just that he says true, if not particularly insightful, things. It’s that he has the moral courage to say them in a culture that has socially delegitimized the truth. Nothing did more to put Peterson on the map than his avowed refusal to comply with Canadian bill C-16, which would criminalize failing to call someone by even completely made up words like “xir” and “zhe.” He said, “I’ve studied authoritarianism for a very long time – for 40 years – and they’re started by people’s attempts to control the ideological and linguistic territory. There’s no way I’m going to use words made up by people who are doing that – not a chance.” Similarly, his interview on Britain’s Channel 4, in which he stood firm in the face of a hostile interviewer without surrendering to her frame drew millions of views. Peterson isn’t just talking academically about masculinity or how men should live, he’s personally demonstrating manly courage in the public arena.

More:

Every day when I scan media about the church, I see pastors and Christian activists standing up and publicly beating their breasts about things like racism and refugees, with positions that are currently in favor culturally. They’ll wave the Christian flag high about these, signing open letters in the Washington Post denouncing Trump’s policies and the like. They are loud and proud about it, and quick to claim that Christianity requires their positions.

But how often do they publicly say something that would get them uninvited from a Manhattan cocktail party? For all too many of them, never.

That’s the difference between the church and Jordan Peterson. While the elite Evangelical cultural engagement crowd is busy suing for peace with the world, he’s laying it on the line. You might protest that he’s a tenured professor and that he’s banked his book advance and his Patreon money. Well, a lot of those Christian pastors have sold a lot of books too. Where are they?

Renn is right about that. I confess that it sticks in my craw to hear from religious leaders and tenured professors who privately praise me for the controversial stances I take on this blog and in speeches I give, but who won’t risk anything to take the same stances within their institutions. Believe me, I understand that many people would risk too much if they stood up. I know these folks, and talk to them all the time. I don’t fault them. The day will surely come when they have no choice but to stand up, but there is real value in being wise, and not martyring yourself until and unless you can make it count. I met someone in Boston last weekend who is deeply closeted as a Christian in her institution. She has not spoken out, but she told me about some serious and consequential good she is doing within the institution, very quietly, to sabotage some really bad things. God bless her; she serves the Kingdom better through her silence at this point.

Anyway, I’m not talking about Christian like her. I’m talking about the people who have a certain protection — from tenure, to cite one example — but who are still afraid to speak, because they don’t want to lose ground within their social and professional networks.

I came across more than a few such people in writing about the Catholic abuse scandal. Parish priests are uniquely vulnerable, in ways that lay people may not appreciate. But I met many a Catholic university professor, businessman, and suchlike who knew what was going on, but who did not want to risk their positions to speak a word for the truth, or for justice for abuse victims. I think also of the white suburban conservative Evangelical pastors and laity in California who would not risk being called bigots by their neighbors for standing publicly against a 2016 bill that, had it been successful, would have shut down scores of Christian colleges in the state. A white Evangelical lay leader told me that if not for the intervention of black Pentecostals and Archbishop Gomez of Los Angeles, they probably would have lost the fight. When the coalition fighting to save these colleges approached big white Evangelical churches to enlist them, most of them refused to take a stand.

The failure of public courage and imagination by orthodox Christians is almost as much a threat to the Church’s future as the actual assaults by those who hate us. But I’m getting ahead of myself here.

Here’s a link to the new issue of The Masculinist, just out, titled “How Bad Are Things Out There?”. Keep in mind that Renn is a Reformed Christian. I can’t remember if he identifies as a conservative Evangelical, but he’s certainly on that team more than any other. I was startled to read in this new issue these paragraphs about The Benedict Option:

Many Evangelicals rejected the Benedict Option. I believe a big part of the reason why is that they simply reject Dreher’s premise that things are getting bad. Instead, if you listen to what they say and look at what they do, it’s pretty obvious that they think things are still going reasonably well. They still have big expansionist visions such converting significant percentages of people in their city, planting large numbers of new churches, etc. that at a minimum suggests that unlike Dreher, they believe Christianity is going to retain significant mainstream appeal. As a video put out by a Manhattan church plant put it, “We’re here because we refuse to believe that this city is hostile to church.”

One of the challenges Dreher ran into with reviewers of his book is that it’s hard in the Evangelical world to get a platform to speak without being very successful already. Successful people, by the very fact of being successful, are biased in favor of thinking conditions are good. Hence there is a structural bias against people who think the situation is bad getting a positive hearing.

There’s a big exception to this – politics, both electoral and within institutions and movements – where the people out of power, even if successful in their own right, are always going to argue things are bad as vector to obtaining power. So I don’t want to suggest that the successful always argue things are good. But it’s a situation that applies in some domains.

The Evangelical world, essentially all of the people with powerful platforms to speak are either a) pastors of very successful megachurches b) leaders of important Evangelical institutions c) their acolytes or others who hope to curry favor with them.

This isn’t the result of nefarious conspiracy but rather common sense. Who are you going to listen to, someone who is successful or someone who is a failure? Who is going to have a bigger audience, the pastor of a 50 person church or the pastor of a 5,000 person church?

More:

Now ask, if you’ve built a 5,000 person megachurch in a major city, are you likely to think that Christianity is losing its appeal or that trends for the faith are poor in America? Probably not. If I were in the shoes of one of those pastors, I think I myself would probably say that things may be different today but they are still ok if we adjust our ministry strategy a bit – say to look more like mine.

The problem comes, as with the innovator’s dilemma in corporate America, when something is wrong but those who recognize it or propose innovative solutions can’t get a hearing because only the successful or representatives of the status quo have a voice. It’s no surprise to me to see that so many innovations and adaptations to new situations happen outside established institutions.

As Eric Hoffer put it in The Ordeal of Change, describing the importance of the role of the “unfit” (his term) in human progress:

It is not usually the successful who advocate drastic social reforms, plunge into new undertakings in business and industry, go out to tame the wilderness, or evolve new modes of expression in literature, art, music, etc. People who make good usually stay where they are and go on doing more and better what they know how to do well.

So no surprise that the people writing book reviews often had a negative view of the Benedict Option. They are representatives of the status quo because they represent, in general, successful institutions.

Renn goes on to advise his readers to

think about how people answer various foundational questions that may not be explicit – that is, to understand their unstated assumptions – when assessing the things they are telling us. Often disagreements are a result of conflicts over implicit premises never directly stated. And we should understand that the people who are successful or in positions of power often have a bias against messages of critique about the state of the organization or movement.

I would also encourage you to think explicitly about your own personal position on the question of the state of the church and society because this will inform at a base level every single thing you do.

Read the entire newsletter. There’s lots more in it, including Renn’s own “personal position.” Please do subscribe to it too. It’s always good news to wake up and see a new issue of The Masculinist in my morning mail. Renn is trying to put together local groups of readers who want to meet up and talk about men, church, and society.

I wish I could have had a digital recorder on during the many conversations I had with faithful, small-o orthodox Christians — Catholic and otherwise — in Boston this past weekend. They are living in an aggressively post-Christian world, one in which all the institutions are hostile to the faith, and in which the Catholic Church has been poleaxed by its own sin and corruption. The conversations I had there were far more like the conversations I have with believers who live in Europe than with Christians in the South and the Midwest.

What Christians who live in parts of the US where the faith hasn’t declined as steeply as it has in New England don’t understand is that the virus is coming for us too. There is no effective quarantine. Of course it’s frightening to face all this, but the failure to face it and figure out what we in the churches can and must do to deal with the crisis is going to result in the total collapse of the faith within our own families and communities. Waiting for a miracle is not a plan.

I’m not going to rehash here the facts about the state of the church and the Christian faith in the US. You’ve heard them all from me here before, and anyway, they’re in my book. If you go to a church that has a lot of people in it, and everybody is engaged with their faith, well, that’s great! But look beyond the walls of your congregation. Look beyond the bounds of your Christian community. Things are not okay. Things are not remotely okay. There are no relatively minor adjustments we can make that will enable the churches to manage this without radical change.

I was in contact recently with a reader whose teenager started attending this year a Catholic school in his city, one that the reader says is popular and full of students. He told me the high school is a mainstay in his city. But the environment there, both in the classrooms and in the general ethos of the school, is inimical to the actual Catholic religion. (The reader gave me specific examples, which I won’t repeat here.) He said that if you look at the school from the outside, it looks fine. But the school itself is not passing on the Catholic faith to its students. In fact, many of the parents would probably be angry if it tried to do that. They want to believe that they are good Catholics who are doing right by their kids by giving them a Catholic education. After our exchange, I was left with the impression that to the parents and the school personnel there, it is more important to them to seem than to be.

At a 2014 conference at First Things magazine, I saw a fascinating exchange between older Catholic academics — retired, or at least long out of the undergraduate classrooms — and younger ones, who have a lot more experience teaching undergraduates these days. The younger ones were trying hard to get the older ones to understand that nearly all of the Catholic undergraduates they teach today come without knowing anything substantive about the Catholic faith — this, even if they have graduated from Catholic high schools! In terms of catechesis and discipleship, the US Catholic Church is in many respects a Potemkin village.

I have been hearing more and more the same kind of thing from Evangelicals engaged in higher education. Pop Evangelicalism, they tell me, some time ago gave itself over to a heavily relational form of Christianity, one that focuses almost entirely on experiences with others. This can have its strengths, to be sure, but the young are given no solid grounding for Christian faith outside of their own emotional experiences.

(Believe me, I’m not being an Orthodox triumphalist on this matter. There are so few Orthodox Christians in the US that I don’t know if there are any reliable data tracking the same phenomena among our institutions and our young. But I would be shocked if most Orthodox young adults — those in some parishes certainly excepted — were any different from our Catholic and Evangelical brethren.)

In 2016, on his blog, Alan Jacobs wrote that he was startled to see some criticism of the Ben Op coming from people he wouldn’t expect to be so critical. He wrote:

The Benedict Option, as I understand it, is based on three premises.

- The dominant media of our technological society are powerful forces for socializing people into modes of thought and action that are often inconsistent with, if not absolutely hostile to, Christian faith and practice.

- In America today, churches and other Christian institutions (schools at all levels, parachurch organizations with various missions) are comparatively very weak at socializing people, if for no other reason than that they have access to comparatively little mindspace.

- Healthy Christian communities are made up of people who have been thoroughly grounded in, thoroughly socialized into, the the historic practices and beliefs of the Christian church.

From these three premises proponents of the Benedict Option draw a conclusion: If we are to form strong Christians, people with robust commitment to and robust understanding of the Christian life, then we need to shift the balance of ideological power towards Christian formation, and that means investing more of our time and attention than we have been spending on strengthening our Christian institutions.

I have to say that I simply do not see how any thoughtful Christian could disagree with any of these premises or the conclusion that follows from them. If any of you do so dissent, please let me know how and why — I would greatly benefit from hearing your views.

Me too. But then, you knew that. We talk about this a lot in this space.

So, look, in light of Aaron Renn’s latest, let me move the conversation away from whether or not the Benedict Option itself is a good response to the crisis. Forget that. Let’s focus on the more foundational questions: Do you think the Christian church is in a critical crisis? Do you think that Christians today are well-formed as distinct Christians? Do you think the churches, Christian schools, and other Christian institutions, are doing a good job forming Christian disciples?

One last thing for you to think about. As I’ve mentioned here, I’ve just started Shoshana Zuboff’s new book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. It’s a real knockout. The book is about how our economy and society are being radically changed by a model of technology-driven capitalism that depends on mining data about our personal lives, and monetizing them. Zuboff talks early on about how the challenge we’re facing now to our politics, our society, and even to human nature, is truly without precedent, which is why we have so much trouble understanding what’s happening, much less forming an adequate response to it.

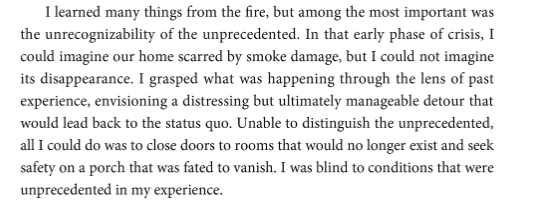

To get her point across, Zuboff uses the example of a house fire that she and her family suffered through. She writes that a few years ago, their house was struck by lightning. When they smelled smoke, the family evacuated. Zuboff thought she would have time to gather a few things before the fire department got there. She ended up having to be pulled out of the burning house at the last moment by the fire marshal. The entire house burned to the ground, and she might have died in the fire, because it was far worse than she had imagined. Zuboff writes:

This is what is happening in the Christian churches now. Nothing like this has happened before, or at least not since around the year 500. So many Christians — priests, pastors, teachers, lay leaders, moms, dads — are running around the burning house trying to close doors and wait for the fire brigade to put out the flames, so we can return to the status quo. They are blind to the unprecedented, radical nature of these conditions. The house as we and our ancestors have known it since time out of mind is burning down to the ground. A lot of us are going to perish in the fire because we did not have the presence of mind to see what was going on right in front of us. This is understandable; even Lot and his family had to be carried out of their doomed city by the angels, because they resisted the angels’ clear warning.

This is understandable. But it’s not excusable, if you appreciate the difference.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.