High Art of the Bourgeoisie

On Saturday an exhibition dedicated to portraits of the painter Edouard Manet opened at the Royal Academy in London to largely strong reviews. Primed to see a parade of characters memorialized for posterity by a realist master, a visitor may be struck by how brief and sketchy the characterizations are and wonder at how this limitation only improves their aesthetic. The figures glow with the luminosity of the painting: the faces are part of the furniture, the eyes are often no more than two black beads. The sitters, even the famous ones, have offered their bodies to the service of color and form. (All except Georges Clemanceau, who said of his, “Manet’s portrait of me? Terrible, I do not have it and do not feel the worse for it. It is in the Louvre, and I wonder why it was put there.”)

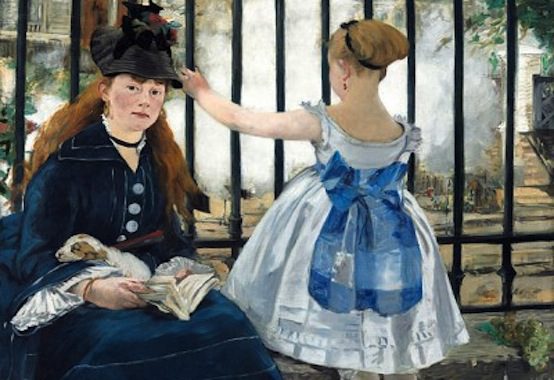

Manet is often hailed as the vanguard of the avant-garde. Luncheon on the Grass repelled the jurors of the Paris Salon in 1863, Olympia disgusted the public in 1865, The Railway was ridiculed in 1872. He experimented with painting his light colors directly onto off-white canvas in order to eliminate the illusion of perspective, created by his immediate predecessors, that arises when the canvas is prepared with a dark matte. He abandoned the traditional style of chiaroscuro, the art of shading shapes with fine gradations of value in order to reproduce their three-dimensional contours, in favor of bold swathes of luscious blues and blacks. The bathing figure in Luncheon (not to be confused with 1868 Luncheon in the Studio) is larger than she ought to be. The locations of the reflections in the mirror in A Bar at the Folies-Bergère make no physical sense, the characters multiplied as in medieval continuous-narrative paintings, the viewer, ingeniously, brought in as one of the characters in the scene.

What a betrayal then, of the militants of modernism, that Manet was by turns surprised and despondent at his repeated rejections at the hands of the academy, the critics, and the public. At the outrage that greeted Olympia in the Salon, where the painting had to be elevated high above a doorway to protect from the crowds who looked ready to tear it to pieces, Manet complained to his long-time friend Charles Baudelaire, “Insults are beating down on me like hail. I’ve never been through anything like it,” to which Baudelaire replied, “Do you think you are the first man put in this predicament? Are you a greater genius than Chateaubriand or Wagner? And did not people make fun of them? They did not die of it.” Baudelaire, whom T.S. Eliot called a great moralist, was busy two hours a day preparing his toilet, encouraging artists to embrace the fleeting triviality of la modernite, and relished the opprobrium of lesser men. Gustave Courbet, a proud realist painter who had entered the Paris scene a decade before Manet, vigorously courted rejection by the academy. Manet had adopted Courbet’s methods, even innovated beyond them, but he did not adopt Courbet’s iconoclastic spirit.

The two major early works that shocked Paris, Luncheon and Olympia, were both styled on classical models. The composition of the three sitters in the first are copied almost exactly from a drawing by Raphael, the Judgment of Paris, a figure of which was inspired by Michelangelo’s creation of Adam at the Sistine Chapel. Olympia has several precedents, most importantly Titian’s Venus of Urbino. His quotation of the classics argued for the equal seriousness of the art of ideal beauty and modern sexuality, rather as Courbet’s 233 square feet Funeral at Ornans had argued for an equivalence of art on historical themes, for which massive canvases were typically reserved, and depictions of dramatic scenes in simple modern life. If the establishment read rebellion into his paintings, it was a rebellion they themselves had incited. The overt eroticism of Titian’s Venus had by the 1860s been denuded of the redeeming features of Renaissance philosophical humanism. Parisian salonistas made do with the haute-couture vulgarity of Alexandre Cabanel’s The Birth of Venus, which, in contrast to the Luncheon, got the establishment stamp of approval in 1863.

Though Manet’s paintings continued to excite controversy, none excited as much as his early works, and they were not intended to. Even his more difficult work began to be featured at the Salon. Daring his most outrageous pieces in the beginning, he had a created a sort of rhetorical space within which, following those early exhibitions, he took pleasure making high art out of real life. The Royal Academy exhibition makes fine inroads into the range and simple dignity of the majority of his life’s work, which for the most part memorialized, with little comment or criticism, the pleasures of the bourgeois life around him. Most of the portraits are not raw portrayals, but formal portraits. The great Railway makes no sense as a picture of a woman and a girl standing next to a railway station. The little girl’s dress is too pretty for soot. The flattened space behind the two figures operates as a classical backdrop rather than an urban landscape.

There is an admirable humility in Manet’s corpus that separates him from his contemporaries. He turned down an invitation to join a dissident art exhibition held by Monet, Renoir, Cézanne, Degas, and other budding impressionists. He preserved that artistic integrity in which art must flow from the soul of the painter, and without which art is merely brittle canvas splashed with resin and oils, without succumbing to the self-satisfied pleasure at the contempt of the ignorant that characterizes the soldiers of the avant-garde.

This is not to say Manet was free from petty conceit, nor, though a Frenchman, from the tangled mess of French pronunciation. His first encounter with Claude Monet, with whom he became lasting friends, was in the third person. During the exhibition of 1865, many people were congratulating Manet on his wonderful seascapes. Confused, he found his way through the exhibition to two canvases, The Mouth of the Seine at Honfleur and The Pointe de la Héve at Low Tide, signed by one ‘Monet.’ Manet demanded to know “who is this Monet whose name sounds just like mine and who is taking advantage of my notoriety?”

Comments