Politics & The Crisis Of Meaning

A reader writes, about a new Pew survey:

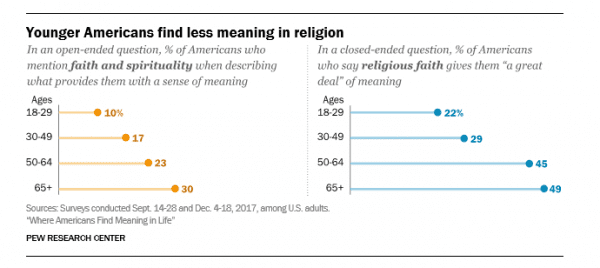

Take a look at the following survey data regarding where Americans find meaning, and the growing gap between the old and young, specifically when it comes to deriving meaning from religion. Now, granted the closed-ended question only captures those who said “a great deal of meaning” so those who find some sort of meaning in religion might be larger, but the open-ended question I think is more revealing.

Here are the data. The “open-ended” question asked survey participants “to describe in their own words what makes their lives feel meaningful, fulfilling or satisfying.” The “closed-ended” question gave them 15 possible choices, forcing them to select one or more:

That is deeply disconcerting for religious believers. Only one in 10 Millennials say faith and spirituality give them meaning. The numbers aren’t particularly high for any demographic group.

I suspect that the open-ended answers are more honest, because when religion is suggested to people, many feel obliged to choose it (e.g., “Well, I guess I really should say ‘religion,’ because I would like to be the sort of person who finds a great deal of meaning from religion”). Even so, look at the huge closed-ended gap on either side of the age 50 line. When forced to make a decision on whether or not religious faith gives them a “great deal” of meaning, the numbers are paltry.

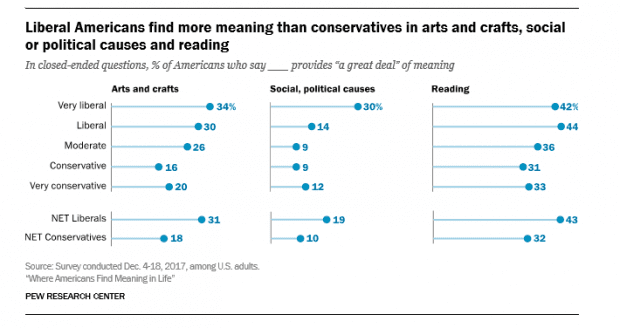

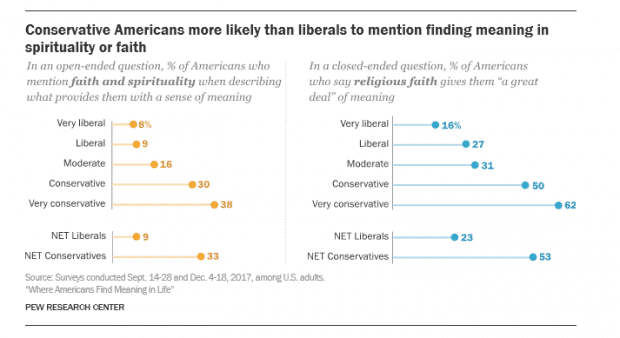

Here are some other interesting results:

Those results tell us clearly — and worryingly — that religion as a source of meaning has become politicized. Most liberals don’t have the deep relationship to religion (as a source of meaning) that most conservatives do. This suggests that liberals are indisposed to understanding why religion matters so much to conservatives, and are indeed likely to associate it with partisan politics. Over the past 20 years or so, we have gone from being a nation where religious liberty, which is one of the bedrocks of classical liberalism, has gone from being something widely supported to being taken by very many people as a code word for hating gays. A country in which taking religion seriously is seen by half the people as something conservatives do is not a country where religious liberty is secure.

It’s comforting to see that only a minority of both liberals and conservatives find a “great deal” of meaning in political and social causes, but notice how strong the numbers are for people who identify as “very liberal.” Politics and social activism serve as a kind of religion for these people. Remember this post from a short time ago on political tribes, and how the “Progressive Activists” are only a small minority, but they wield disproportionate power because they are strongly represented among the elites:

Compared with the rest of the (nationally representative) polling sample, progressive activists are much more likely to be rich, highly educated—and white. They are nearly twice as likely as the average to make more than $100,000 a year. They are nearly three times as likely to have a postgraduate degree. And while 12 percent of the overall sample in the study is African American, only 3 percent of progressive activists are. With the exception of the small tribe of devoted conservatives, progressive activists are the most racially homogeneous group in the country.

If you look at the Pew results, you’ll see that African-Americans are significantly more likely than other Americans to say that religion gives their lives meaning.

Here’s what concerns me: that the “very liberal” who find a “great deal” of meaning in politics and social activism — which by definition are not private matters — will treat politics and social activism as a substitute religion. And, given their disproportionate representation among the elites, that this will cause a world of trouble for us religious people, who will be seen by those liberal activists as nothing other than their political enemies at prayer.

Many progressive elites — which, according to the Hidden Tribes study, include not only elite, highly educated, well-paid professionals, but also young urban whites — are using politics and social activism to fill the hunger for meaning left by their abandonment of religion. The 20th century saw the rise and fall of ersatz political religions in Europe — fascism and communism — to replace the gap left by the death of Christianity. When people living in the West today who endured communism tell us that this current moment in militant, institutionalized wokeness Western culture reminds them of communism’s advent in their native lands, we had better pay attention.

The reader who sent me the Pew findings writes:

I was recently reminded by a colleague of the centrality of meaning to work and life and how, in turn, individuals approach work, life, relationships, etc. based off their perceived, conceived, lived interaction with the meaningfulness of an endeavor. The encounter brought to mind a question, how much of our lives are lived in meaning vacuums? That is, does anyone even ponder the meaning or teleology of an event, relationship, action? Or, do we move along with the implicit understanding that objective meaning is non-existent, and what is is merely the subjective move to react and squeeze as much pleasure out of the moment, person, action as possible? If materialistic-naturalism is to be believed, then, yes, that is all there is, mere momentary pleasure of the senses. I wonder if this is simply borne out further by the rest of the Pew Survey, and would be driven home by a deeper analysis of the elements of meaning captured in the survey.

I bet if the question of how one can/should construct meaning, rather than merely where do they find meaning, was asked of the survey participants an overwhelming amount of Americans would say through the senses/emotions, even the religious. This bastardization of meaning to merely sensual is evidence of our devolution from Man to Beast. Lewis’s Abolition of Man is well under way. I find hope though in the fact that Man is objectively a certain type of being, designed for a certain end, and these ends cannot be erased. We will burn ourselves out with the pleasures of liquid modernity, but in the end I do believe, given this God created teleology, a return to true meaning will begin.

That’s a smart observation. Along those lines, I’d like to point you all to this excellent Commonweal essay by Carlo Lancellotti, a regular commenter on this blog and the translator of the work of Italian political philosopher Augusto Del Noce (1910-1989). Excerpt:

Nonetheless, after World War II Marxism experienced a resurgence in Western Europe, not only among intellectuals and politicians but also in mainstream culture. But Del Noce noticed that at the same time society was moving in a very different direction from what Marx had predicted: capitalism kept expanding, people were eagerly embracing consumerism, and the prospect of a Communist revolution seemed more and more remote. To Del Noce, this simultaneous success and defeat of Marxism pointed to a deep contradiction. On the one hand, Marx had taught historical materialism, the doctrine that metaphysical and ethical ideas are just ideological covers for economic and political interests. On the other hand, he had prophesied that the expansion of capitalism would inevitably lead to revolution, followed by the “new man,” the “classless society,” the “reign of freedom.” But what if the revolution did not arrive, if the “new man” never materialized?

In that case, Del Noce realized, Marxist historical materialism would degenerate into a form of radical relativism—into the idea that philosophical and moral concepts are just reflections of historical and economic circumstances and have no permanent validity. This would have to include the concept of injustice, without which a critique of capitalism would be hard, if not impossible, to uphold. A post-Marxist culture—one that kept Marx’s radical materialism and denial of religious transcendence, while dispensing with his confident predictions about the self-destruction of capitalism—would naturally tend to be radically bourgeois. By that, Del Noce meant a society that views “everything as an object of trade” and “as an instrument” to be used in the pursuit of individualized “well-being.” Such bourgeois society would be highly individualistic, because it could not recognize any cultural or religious “common good.” In the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels described the power of the bourgeois worldview to dissolve all cultural and religious allegiances into a universal market. Now, ironically, Marxist ideas (which Del Noce viewed as a much larger and more influential phenomenon than political Marxism in a strict sense) had helped bring that process to completion. At a conference in Rome in 1968, Del Noce looked back at recent history and concluded that the post-Marxist culture would be “a society that accepts all of Marxism’s negations against contemplative thought, religion, and metaphysics; that accepts, therefore, the Marxist reduction of ideas to instruments of production. But which, on the other hand, rejects the revolutionary-messianic aspects of Marxism, and thus all the religious elements that remain within the revolutionary idea. In this regard, it truly represents the bourgeois spirit in its pure state, the bourgeois spirit triumphant over its two traditional adversaries, transcendent religion and revolutionary thought.”

And there’s this, from a Michael Hanby review of a Del Noce book (translated by Lancellotti):

Marxism was a much less viable political force in America than it was in Europe, but that did not make America immune to technocratic absolutism. Del Noce understands that the essential metaphysical presuppositions of technocracy—the reduction of form to force, being to history, substance to operation, truth to function, knowledge to engineering, and authority to power—were present in America long before the arrival of the Frankfurt School. He concurs with Reich that America is the most fertile soil for sexual revolution and quotes approvingly the words penned by Sciacca in 1954, when American anti-communism was strong.

Even if society in the United States calls itself Christian, American philosophy is essentially all atheistic. Not only that: it is marked by the idolatry of science, the tool that will radically change humanity by producing technical development, and will bring to mankind all the happiness that man by his ‘nature’ can desire.

What does this Del Noce material have to do with the Pew “meaning” survey data? Among other things, Del Noce believed that a recovery of Being (which entails a recovery of a richly metaphysical Christianity, not the moralistic attenuated version popular today) is the only thing that could save the West from the materialist ideologies that have become deeply embedded in its post-Christian life. Del Noce has written:

The immediate prospect, if progressivism succeeds, is the most despotic conservatism that ever appeared in history, because its premise is the absolute obliteration of the idea of another reality, either earthly or heavenly. There would be no lack of agreement with … the new theologians of the post-Christian age, who proclaim the end of all myths and all transcendent illusions. But a regime that puts an end to hope is the very definition of the greatest degree that an oppressive system can reach.

Lancellotti, in his Commonweal essay, makes the point clearer:

In particular, according to Del Noce, there is an implicit philosophical question that dominates contemporary politics. It is the struggle between two “philosophical anthropologies”:

The true clash is between two conceptions of life. One could be described in terms of the religious dimension or of the presence of the divine in us; it certainly achieves its fullness in Christian thought, or in fact in Catholic thought, but it is not per se specifically Christian in the proper sense…. According to the second conception—the instrumentalist one, found in positivism, pragmatism, Marxism, and evolutionism in general, in its philosophic extension—there is nothing in spirit and in reason that possesses an independent metaphysical origin.

To Del Noce, the religious dimension meant that human beings are not reducible to sociological, economic, and biological factors. As Domenach had put it, “in man there is always something more.” To be human means to be able to raise questions of meaning that transcend our historical-material context—including religious questions.

To sum up: the West’s crisis of meaning may well end up with ideological tyranny, and the only thing that can save us from it is a rediscovery of true religion. The loss of the religious sense among Western peoples, which is acutely present among the younger generations, means we are entering a difficult time, especially for religious believers, who, because they are so heavily concentrated on the political right, may be subject to political suppression, even persecution.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.