Imagination and the Artistic Value of Calvin & Hobbes

Bill Watterson’s comic series Calvin and Hobbes has inspired a religious following since its publication. Even after its retirement in 1995, millions of readers remained devoted to the series. Now a new film documentary called “Dear Mr. Watterson,” opening in theaters November 15, explores how comic book characters could inspire such devotion.

“Little can compare to the nostalgic value of that particular comic strip,” says TIME in a story on the documentary. “And it’s not just nostalgia: the artistic value and the message of Calvin has endured, as is discussed by the fans who make appearances in the film.”

But can a comic strip really have “artistic value?” It’s a concept Watterson personally promoted throughout his career. He was a political science major from Ohio’s Kenyon College, and painted Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam on his dorm room ceiling sophomore year. He named six-year-old Calvin after John Calvin, the 16th-century Christian theologian, and Hobbes after 17th-century political philosopher Thomas Hobbes.

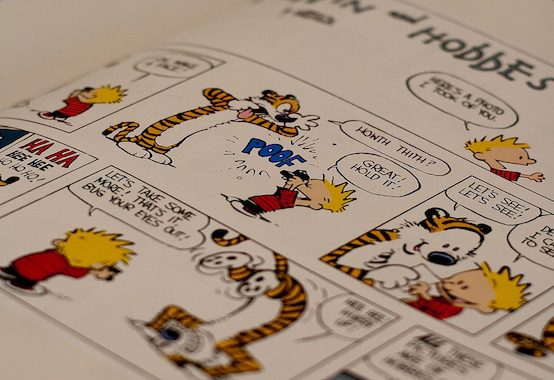

The comic focused on tomfoolery between Calvin and his stuffed tiger. Often, Calvin and Hobbes’ witty banter ventured into the philosophic, theological, and political. Calvin discussed “haranguing the multitudes,” “literalism”, and “self-actualizing anima.” Even with its intellectualism, the comic was a fantastic hit: in a 1987 article, The Plain Dealer reported it was No. 1 in reader support in several papers, and had already reached 500,000 book sales. Watterson was “shell-shocked” by his sudden celebrity status.

When Watterson retired Calvin and Hobbes, readers were devastated. But Watterson said, “If I had rolled along with the strip’s popularity and repeated myself for another five, 10 or 20 years, the people now ‘grieving’ for Calvin and Hobbes would be wishing me dead and cursing newspapers for running tedious, ancient strips like mine…” Watterson was also weary of pressure to merchandise Calvin and Hobbes. For him, Calvin and Hobbes were more than lucrative pop art to plaster on t-shirts. He had an artist’s stubborn loyalty to the integrity of his craft: “The so-called ‘opportunity’ I faced would have meant giving up my individual voice for that of a money-grubbing corporation,” he said in a 1990 Kenyon College Commencement Speech. “It would have meant my purpose in writing was to sell things, not say things. My pride in craft would be sacrificed to the efficiency of mass production and the work of assistants. Authorship would become committee decision. Creativity would become work for pay. Art would turn into commerce.”

Watterson was passionate about the potential of comics, and upset when newspapers tried to limit their artists. “I think that papers are killing the art form,” he told the Plain Dealer. Publishers had reduced cartoon space, thus forcing cartoonists to simplify their work. “Adventure strips have gone right down the tubes. Strips are just getting stupider because they have to be so simple. There’s no drawing, no movement, no expression.”

The term “artistic value” usually references elegant museum works. But Watterson’s daily comic appeared in inky newsprint pages, and was probably used to wrap fish in the market or bundle antiques in attic boxes. Webster’s 1913 dictionary says high art “deals with lofty and dignified subjects and is characterized by an elevated style avoiding all meretricious display.” Watterson avoided “meretricious display” – but could one call facetious, belching Calvin a “lofty and dignified subject?” Probably not. However, Stuart Platter’s definition of “high art” in High Art Down Home is worth considering:

“For the connoisseur, high art can stimulate intense emotional and intellectual responses. This book will show that people often love the art that they buy, in the serious meaning of the term. Something that is merely decorative cannot help one to see the world differently and cannot change the appreciation of reality, as high art can for those few with the educated capacity to appreciate it.”

Calvin and Hobbes has inspired “emotional and intellectual responses,” and even “love.” It has the ability to “change the appreciation of reality.” Yet it is not limited to elite connoisseurs: if Facebook’s Daily Calvin and Hobbes page is any indication, the comic is appreciated by thousands.

While Calvin and Hobbes may or may not inspire “transcendent” philosophizing, it need not be confined to the realm of low art. Watterson demonstrated the ability of his medium to be artistically meaningful. Calvin, with all his mud and antics, may be more transcendent than we think.

Comments