How Not to Read the Declaration

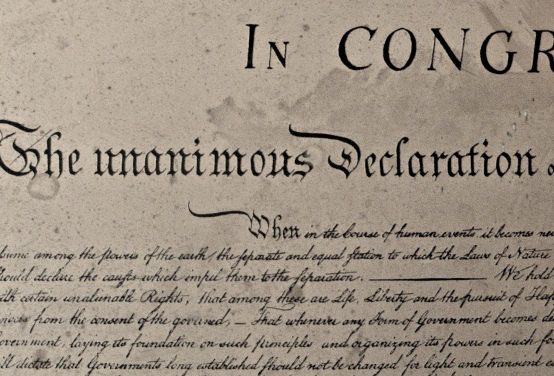

A new book — For Liberty and Equality by John Tsesis — explores the influence of the Declaration of Independence on U.S. history, from the document’s drafting to the present. But from the sound of Jack Rakove’s review, the book get the relationship between the Declaration and the Constitution very wrong:

Tsesis gives Jefferson’s concise statements an extraordinarily authoritative sweep. The Declaration’s “message of universal freedoms,” he asserts early on, remains “the national manifesto of representative democracy and fundamental rights.” Or again, “The Declaration created a unified national government”; it “established a national polity composed of states, while the original Constitution granted states the authority to run their own day-to-day operations.” The Constitution, in this view, remains a partial and less-than-perfect instrument for achieving the ends of the Declaration. …

These are powerful moral claims, but as statements of history they are highly problematic. The Declaration was the act of a national government that already existed, in the form of the Continental Congress, but the question of how unified its authority would be was left open, to be settled first by the Articles of Confederation and then significantly amplified and restructured by the Constitution. Nor did the Constitution “grant” the states any authority. That authority already existed. The Constitution only modified it by giving the national government independent legal powers of its own while imposing some restrictions on the legislative power of the states. The Continental Congress did decide that the independent states should be governed as republics—whatever choice was there?—but it did this not through the Declaration of July 4, but in another resolution approved seven weeks earlier.

Rakove himself is torn: the Declaration does not establish the ends of the Constitution, as the likes of “Harry Jaffa, high priest emeritus of the Claremont Straussians” would have it. But Lincoln did expand the Declaration’s rhetoric into a national mission of sorts during the Civil War. Historical honesty requires one narrative, while understanding Lincoln’s mythopoesis, which planted equality at the center of the American tradition, may require another. “Lincoln’s vision of the Declaration … engages us far more deeply than the more prosaic interpretations that historians are duty-bound to produce.”

That’s the problem. Lincoln’s “vision of the Declaration” is so engaging for many Americans — particularly for dreamers and con men in the press, academy, and politics — that it threatens to blot out the Constitution. To say this is not to deny the place that high ideals may have in American politics, including the ideal of equality in one form or another. But those ideals do not have to be rooted in the Declaration, and equality is but one among several that Americans must deliberate over. The Constitution is meant to make that deliberation possible, both through the structure it creates and by the modest ends — “domestic tranquility” and the like — it attempts to secure. Replacing the carefully considered and debated Constitution, in all its modesty, with the passionate idealism of wartime rhetoric is a prescription for crusading in place of governing.

Comments