The Universality of Bigotry

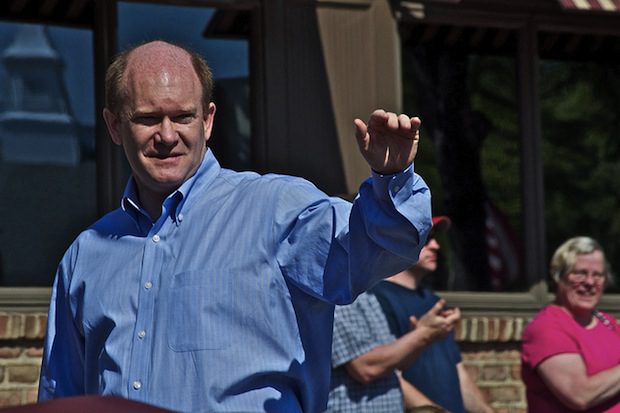

E.J. Dionne tells a great story about a talk Sen. Chris Coons, the Delaware Democrat, gave to an atheist group recently. In his presentation, Coons agreed with them that nonbelievers have often gotten a raw deal from the religious. Dionne:

If Coons had left it at that, this would have been another in a long series of Washington speeches in which a politician tells his allies how much he agrees with them. But as “a practicing Christian and a devout Presbyterian,” Coons had a second message.

Early on, he quoted the very Bible others find offensive, noting that Jesus’s command in Matthew: 25 to feed the hungry, clothe the naked and visit the imprisoned had “driven” him throughout his life. As a young man, he spent time in Kenya and South Africa working with the poor and with leaders of the South African Council of Churches, including Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

And then he told a story. As a Yale Law School student, he decided to pursue a separate degree from the university’s divinity school, and what he encountered was a long way from tolerance and open-mindedness.

“I was very active in the progressive community in my law school, and most of my friends were politically active progressives,” he said. “But I was unprepared for their response when word started filtering out that I had enrolled in divinity school. Some of them literally disowned me; my own roommates moved out. Several folks literally stopped speaking to me and acted as if I had lost my mind.”

His own background was thrown in his face, with friends saying: “Chris, you’re a scientist, you’re a chemist, you trained as a chemist as an undergraduate, how could you possibly believe this insane stuff?”

What he experienced, Coons said, was “real bigotry.”

“Frankly, we were a group of progressives who were really proud of how welcoming and open we were and how virtually any possible lifestyle or worldview or attitude was something we would embrace — right up until the moment when I said I believed in God.” For many progressives, “accepting someone of expressed faith was one of the hardest moments of tolerance and inclusion for them.”

One of my friends experienced something similar in a progressive seminary. My friend found that the seminarians were all middle-class white liberals who nearly broke their arms patting themselves on the back for their progressivism, but who had no idea how close-minded and judgmental they were toward people who didn’t share their politics or worldview.

I think it’s hard for people in general to grasp that you can like and respect other people very different from yourself without agreeing with them. It’s possible. And it’s not only possible, it’s often necessary. A conservative friend said to me the other day that he didn’t understand how I could be friends with Andrew Sullivan (I’m sure Sullivan gets that about me a hundred times more often than I get it about him). I told him that Andrew and I don’t agree on some important things, but he is a kind and thoughtful man, and in any case is made in the image of God, like all of us.

Look, Franklin Evans, a longtime reader of this blog, is the kind of person that I, a conservative Christian, am supposed to find weird and alien and a threat. He’s a liberal, and a practicing pagan. I love the guy. He’s got a big heart, and a heart for justice. I learn from him. Some of my closest friends are liberals, even atheists. Has it always been the case in this country that disagreement should make us enemies?

I have a friend who wrote me today about the blowback he’s receiving for a public talk he recently gave. I’m not going to be specific, because I want to protect his privacy. I found a recording of the talk, and listened to it. It was basically a call to love and respect others, and to fight hatred and strife by attending to the sources of it within our own hearts. I could not imagine what problem people would have with it. Yet someone in the audience — an activist type — was horribly offended because of what he didn’t say that the activist believed he ought to have said, and read him the riot act. Now, he says, the activist is going around his community telling folks that he’s a bigot.

It’s discouraging how people are so eager to see the worst in others. I find that I am often challenged, in a good way, by the very different people I meet in the course of my work. From How Dante Can Save Your Life:

And he [Mike Holmes, my therapist] made fruitful connections that I could not. One week I briefed him on a trip I had made to Wisconsin a few days earlier, to lecture at a small Lutheran college about Little Way. After my talk, I met a transgendered man and his wife in the audience. They had read my book, loved it, and wanted to hear me speak. But they had been afraid to come because they knew I was a Christian, and a conservative one. The couple feared judgment and rejection, but they had come anyway, on the advice of a friend.

“It’s funny, Mike,” I told him. “These are not the kind of people I hang out with, but they really impressed me. They were kind and spiritually serious. I enjoyed talking with them. Even though we are so different, we made a connection. I’ve been thinking about that all week. There was something really human that passed between us, and it kind of knocked me back.”

“Now that’s interesting,” Mike said. “You saw that couple as different, maybe even strange by your standards, but you saw them as real people. Let’s take that thought and apply it to your family. Can you see them as different, and extend to them the same grace?”

This is hard work. It’s hard work for me, and it’s hard work for anybody. I collaborated closely with an African-American man on a project that I’ll be able to tell you about later, and this collaboration changed my way of seeing the world. I should say, is changing the way I see the world. I’m not saying that everything can be kum-ba-yah all the time, and that the differences between people are only superficial. Sometimes there really are irreconcilable differences in worldviews, and it’s important to recognize that. Disagreement, even strong disagreement, is not necessarily personal. What I’m saying is that these differences are often easier to ameliorate, if not overcome, than we think — if we want to do so. The truth is that many of us would rather rest in our hatreds, especially if hating the Other gives us the liberty to ignore our own faults and contributions to the problem.

One of the most difficult things for me to keep front to mind is that just because somebody hates me, and hates people like me, that does not give me license to hate them back. I told my friend today — the one who gave the speech that has him in trouble with activists — that the activist sounds like an extremely angry person, and that anger, as Dante shows us, makes us blind. We flail in the dark, not caring who we destroy. This is one of my great temptations.

UPDATE: I really like this comment from reader Liam:

This is something I experienced in high school on suburban Long Island in the late 1970s. Teachers who were very secularized (Jewish, Catholic, Protestant): the better ones were on to their own cognitive/spiritual blindspots, while others were not, and I had a field day over 3 years puncturing epistemic bubbles with some frequency (I was a loner, and had little to risk at that point), especially on their self-conceit as broad-minded. I did it with humor, likely sprinkled with sarcasm (but not cynicism or a sense of aggrievement). It generally had positive effects, I think, though I certainly misfired on occasion, too. Teachers could slide into viewing belief the way viewers at museums view works of sacred art – reified and out of context. But I didn’t go into this with a sense of warfare or resentment, but more a sense of adventure. One’s attitude bears a lot on whether one can build relationships.

Interestingly, I found Harvard Law School, in the depth of its Beirut-on-The-Charles years, to be more genuinely respectful of sincere religious belief. (Oh, to be sure, there were genuinely mockable instances of self-conceit, like the chalkboard notices I encountered in my first week of classes inviting “Progressive Persons and Their Friends”…). I just got to see what happened to many (NOT all) of the properly networked conservatives when Reagan was reelected in a landslide – 1985 was something like 1965 was for liberals – a peak moment when power started to matter more than principle. It was then I began to see how much movement progressives and movement conservatives had in common. Then again, I’ve always found continuities more interesting than discontinuities, partly because the novelty of the latter gives them undue cognitive emphasis.

As an actively practing believer most of whose close friends have left active practice, it’s something that I deal with on a personal rather than abstract basis. Each relationship is different – so I rather strongly resist universalizing too much from them altogether. There are the friends who confronted and judged me – and to whom I basically said, “You get a vote in my spiritual life when you take responsibility for it.” There were some friends who mocked me on occasion, and I engaged in some mirroring that was designed to shed more light than heat (a very important difference to keep in mind). Then there were friends who had a don’t-ask-don’t-tell approach. And then others who always maintained genuine respect. And some friends who faded away. It’s a mix of stuff that I’ve navigated over many years.

So I am very much sympathetic to issues of this sort. My experience and, to be truthful, my Christian call requires me to give much more priority to the concrete particulars of each relationships than to make them fit a grander theory. Grandiosity is invariably not coming from a Spirit-filled place: too much ego resisting theosis.

Perhaps people in more conservative areas have been more sheltered from this (for different reasons in different areas – in the upper Midwest, for example, the cultural imperative to Be Nice can have quite a chilling effect on engaging these issues, for ill and for good). But for others of us, it’s been going on for decades.

Interestingly, our family dentist (and his wife) when I was growing up was active in the Ethical Culture movement (it was a significant if not big deal in the mid-20th century New York area). I got to witness my parents have very deep and engaging sharings with my dentist and his wife. There was significant disagreement, and friendship and mutual respect. I guess I took that as a model for what could be possible.

When ego dominates, much less is possible. When malice erupts, even less. And I think cynicism is probably worse, as it’s frozen (at least malice has some heat).

F*ck ego, f*ck malice, and f*ck cynicism. You can quote me on that.

I know there are some things we don’t agree on, but I bet we could be good neighbors, and eat well together.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.