Social Gospel Über Alles

A reader who goes by the nom de blog “John Carter” comments on the “Are Christians to Blame For the EU Migrant Crisis?” thread:

So, I’ve moved to Germany in August and let me tell you that your commentator is both right, but also being read (i think) a bit wrong. Having attended a state run Lutheran Church since I’ve moved here, I’ve pretty much written off the state church. What we consider Christianity, and whatever is going on in the Church here are two completely opposite things.

I knew things weren’t going to be perfect (somewhere online, either on the dioceses website or the Evangelical conference everything lines up with what we’d consider orthodoxy except for ‘families’ which made the vague statement ‘We accept families of all stripes” while including a picture of a traditional family over a rainbow…), but I never expected the mind numbing weirdness I’ve witnessed. While the Church for the most part seems to be rather traditional from first glance it’s anything but. This goes beyond the butt-ugly mid-century modern altar piece in the medieval parish a few blocks away from mine, but to things like playing ‘Abbey Road’ and ‘Remember’ as Communion music. When it comes to refugees, it’s the Church’s obsession. Much of Germany is making a lot of noise about being helpful and welcoming (I think the cultural powers want to prove Germany’s more than the purse-string holding sourpuss they get the reputation for), but the Church makes the biggest din. Which would be fine, but the method they go about it chills me.

We had someone from higher up a few months ago (I’m assuming he was a Pastor at a higher level because he lead the benediction and gave the homely) come and as his homely, reminded us that Jesus wants us to love out enemies (good, I can get behind that), that even if there are black sheep we can’t judge all refugees by their actions (ok, I get that to a point), that we need to sit at a table with them and listen (ok, again, to a point). But then he gets to the point where he says we must do this, not because Christ mandates this, or to spread the gospel to those needing it most, but because we had blood on our hands. Apparently Germany is the biggest exporter of guns in the EU to this region, and me (a college student and dual citizen that hasn’t been in the country in years, nor done anything political here) and about 30 elderly people were responsible as well. I was sitting there boiling, “what the heck was THAT??” I fumed. Similarly, Christmas Mass’ homily was awkwardly shoe horned into the worst example of bad ideas. Recycling the really really bad example of the Christmas Story being a parallel for the refugees (Ummm, No. Why do Facebook feeds and everyone always choose this example? There’s a difference going to a strange culture to escape war, and doing a cross country trip and not being able to find a hotel room. If we are going to do a parallel fine, but why the heck not ‘The Flight to Egypt’? that would make much better sense…), a lot of the congregation looked around with annoyed faces but they continue.

Honestly, the real point I’m trying to make is that the Church here (I’m becoming more and more certain) doesn’t believe in it’s own message or it’s own story. They want to play interfaith niceness, and operate as a social services office with nice traditions. I’ve seen a lot of weird heretical things in my life, but the cake is taken by the ‘Evening of Reflection’ offered at the start of the church calendar earlier this month.What I took was going to be prayer and reflection about holy things and preparation for the up coming year, ended up being a new age workshop being run by one of the Diocese’s pastors(!). Making sure our circle of chairs stayed unbroken, telling us about the time he met the spirit of his childhood self in the woods in Canada. Having us meditate and “allow our spirits to float between heaven and earth’ (and yes there was a gong), listening to a Audiobook psychiatrist who explained childhood traumas and then asked us to meditate like we were a baby who had just been nursed and was being lovingly held. It was weird, and despite the repeating of ‘God called the little ones unto him’ there was really nothing remotely related to our supposed common faith. The straw that broke the camel’s back was him pulling out a deck of cards, reminding us that they were ‘powerful’ and that by choosing one we’d discover a true secret of our soul. I don’t think I’ve lied in church in ages, but I quickly excused myself for the bathroom and returned home.

That’s the kind of things you’d expect from your garden variety cult, or weird snake-handling fundies , but this is a STATE CHURCH in a majorly ‘Christian Nation’. What’s worse, is that despite the fact that the churches are usually filled with older people, there’s still a catechism class. Every once in a while, there’s about 12 or so teens or children, with their little attendance cards. Rarely did I see them outside of required visits, but I have to wonder. These kids’ only exposure to the Gospel (unless they’re lucky enough to have good parents who teach them at home) is going to be along the check-list for conformation, and the people doing it don’t behave if they even believe it. Whatever Christianity your original commentator is complaining about, I’ve pretty certain it’s this one. And while I can only speak from what’s I’ve seen the last few months in the Lutheran Church, I wouldn’t be surprised if a lot of Catholicism is in the same boat. This Christianity is Dead, and is a sick monster wearing the robes of its fore bearer, while everyone either doesn’t care or is too blind to see it.

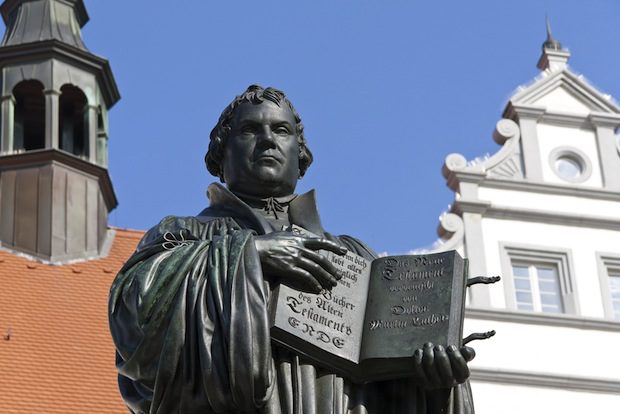

In a few years we’ll be celebrating the anniversary of the Reformation, ironically we’ll be needing another one if things don’t shape up.And it’s kind of sad really, I’ve really not met anyone my age or even anyone my parents age that seem to take faith really seriously. Ironically, the most understanding people have been the muslims my age. Though it still makes me slightly uncomfortable that as seriously that they take their faith, They may be the sign that my own is going to disappear…

But that’s just from your over-opinionated college boy, whatever my two cents are worth.

Question to European readers: is this what things look like in established churches where you live? If yes, please give details — and if not, what is making the difference?

This anecdote reminds me of church historian Robert Louis Wilken’s 2004 reflection, “The Church As Culture,” after spending some time in Germany. Forgive me for quoting this essay often, but it’s so, so important. Excerpt:

Talking to the young woman in Erfurt and listening in on the debate about the EU constitution I found myself musing on the future of Christian culture. In my lifetime we have witnessed the collapse of Christian civilization. At first the process of disintegration was slow, a gradual and persistent attrition, but today it has moved into overdrive, and what is more troubling, it has become deliberate and intentional, not only promoted by the cultured despisers of Christianity but often aided and abetted by Christians themselves. [Emphasis mine — RD]

It’s not just in Europe, Wilken says, but in the US as well. More:

Nothing is more needful today than the survival of Christian culture, because in recent generations this culture has become dangerously thin. At this moment in the Church’s history in this country (and in the West more generally) it is less urgent to convince the alternative culture in which we live of the truth of Christ than it is for the Church to tell itself its own story and to nurture its own life [Emphasis mine — RD], the culture of the city of God, the Christian republic. This is not going to happen without a rebirth of moral and spiritual discipline and a resolute effort on the part of Christians to comprehend and to defend the remnants of Christian culture. The unhappy fact is that the society in which we live is no longer neutral about Christianity. The United States would be a much less hospitable environment for the practice of the faith if all the marks of Christian culture were stripped from our public life and Christian behavior were tolerated only in restricted situations.

If Christian culture is to be renewed, habits are more vital than revivals, rituals more edifying than spiritual highs, the creed more penetrating than theological insight, and the celebration of saints’ days more uplifting than the observance of Mother’s Day. There is great wisdom in the maligned phrase ex opere operato, the effect is in the doing. Intention is like a reed blowing in the wind. It is the doing that counts, and if we do something for God, in the doing God does something for us.

I know that some Evangelicals and Catholics instinctively recoil from talk of the Benedict Option, the point of which is primarily “for the Church to tell itself its own story and to nurture its own life,” because we Christians cannot be what we are supposed to be for the world if we lose touch with our own story and our own life. They are under the impression that the Benedict Option is a turning-inward for its own sake, a refusal to evangelize, to tell the Church’s story to the unconverted in the world.

They are wrong, and their error has consequences. First, no church can be authentically Christian without evangelizing. That is perfectly clear from Scripture and Tradition. So let’s get out of the way the idea that the Ben Op is against evangelization.

The situation becomes more complicated when we ask: “What is the goal of evangelism?”

An Evangelical would say, “To lead unbelievers into a saving relationship with Jesus Christ,” by which she would mean leading them to confessing their sinfulness and need for a Savior, and accepting Christ into their hearts as Lord.

A Catholic would say, though perhaps not exactly in these words, “To lead unbelievers into a saving relationship with Jesus Christ, both in and through his Church, which is the ordinary means of salvation He established.” The Catholic would consider her evangelism successful if an unbeliever professed Christ as Lord, and was baptized or confirmed in the Roman Catholic Church, and took up its sacramental life.

An Orthodox evangelist would, in general, treat the goal of evangelism as a Catholic would, only accepting Orthodoxy, not Catholicism, as the historical and theological norm.

Here’s the problem with all of these cases: after the decision has been made for Christ (and, if baptism and/or confirmation [in Orthodoxy, called chrismation] has been performed) … what next?

The Christian life, properly understood, cannot be merely a set of propositions agreed to, but must also be a way of life. And that requires a culture, which is to say, the realization in a material way — in deeds, in language, in song, in drama, in practices, etc. — of the propositions taught by Christianity. To be perfectly clear, at the core of all this is a living spiritual relationship with God, one that cannot be reduced to words, deeds, or beliefs.

In 2009, the Evangelical market researcher and pollster George Barna, talking about the deficits among American Christians in understanding basic Christian orthodoxy, said:

There are a several troubling patterns to take notice. First, although most Americans consider themselves to be Christian and say they know the content of the Bible, less than one out of ten Americans demonstrate such knowledge through their actions. Second, the generational pattern suggests that parents are not focused on guiding their children to have a biblical worldview. One of the challenges for parents, though, is that you cannot give what you do not have, and most parents do not possess such a perspective on life. That raises a third challenge, which relates to the job that Christian churches, schools and parachurch ministries are doing in Christian education. Finally, even though a central element of being a Christian is to embrace basic biblical principles and incorporate them into one’s worldview, there has been no change in the percentage of adults or even born again adults in the past 13 years regarding the possession of a biblical worldview.

If you follow that link (to a Christianity Today account of Barna’s findings), you’ll see that if you are a small-o orthodox Christian, the term “Biblical worldview” is not as contentious as you might suspect, given its use by an Evangelical pollster. I bring it up here because Barna’s research findings mirror exactly the anecdotal accounts I have received over the past three years from a number of Christian educators, both Evangelical and Catholic, in both high school and college. No matter how fervent their faith appears on the surface, there is not much content to it, they say.

Of course from the perspective of people who take Christianity seriously, this is never good. But when the broader culture itself operated from generally Christian principles, it gave a certain margin for laxity. Growing up in the 1970s, in my home, we lived pretty much as nominal Christians, as lots of people we knew did. Yet my sister and I, though only intermittent attenders at Sunday school, learned a lot of the Biblical story from the ambient culture. My parents were by no means unusual in the local popular culture of the time.

It is hard to express to younger people who only know American life in the age of cable television and then the Internet how powerful local culture was at setting the frames through which you saw the world. This could be very bad — for example, it was hard for a white kid growing up in that world to grasp how pervasive racism was, or what it meant — but it could also be very good.

There was very little in the way my generation was raised as Christians to prepare us for the world that was about to be upon us. This is understandable, given how radical those technological changes were. Yesterday I spent 20 minutes FaceTiming my Dutch friend Marnix. When we first became friends, back in 1981, we could only communicate through letters, and the occasional (expensive) phone call. Now, we’re middle-aged husbands and fathers who can communicate through live video links from the comfort of our own couches — and our children can scarcely imagine anything else.

When I was a kid in the 1970s, airlines were regulated, and the cost of flying was astronomical (don’t believe me? Look here). The idea of air travel at all was unusual to middle and working-class people like us, and the thought of traveling to Europe was impossibly exotic. It was not remotely affordable. By contrast, my children have flown a fair amount, and have even been to Europe (my oldest has been four times). The real and (more importantly) imaginary boundaries of their world are far, far beyond what my own were as a child.

It’s like this: when we were kids, the word “atheist” was associated with an aggressively unpleasant woman named Madalyn Murray O’Hair. In my town, many, and probably most, people did not go to church every Sunday, but the idea that there would people who did not believe in God was scarcely thinkable. We would hear about this Madalyn Murray O’Hair woman in the media from time to time, and she was thought of as a bizarre troll.

Now, atheism is thoroughly mainstream. That’s not to say most people are atheists, of course, or that atheism is no big deal in our culture. But it is to say that children born to Christian families nowadays have to confront atheism in ways that my generation did not. Are we preparing our kids for this world?

And not just atheism, of course. As you know, nearly half of all Americans who belong to a church or profess a religion are in another church or religion than the one in which they were raised (I am among their number). I’ve written before about how my father could not understand how I could convert to Catholicism when “the Drehers have always been Methodist.” In truth, any Catholic parent around here of my dad and mom’s generation would have had the same reaction had their child told them that he was becoming an Evangelical. It just wasn’t done.

But now it’s done. It’s done a lot. Again, are we preparing our kids for this world?

The evidence indicates that we are not (::cough, cough:::MTD:::cough, cough:::). Why? That’s complicated, and going into it would make this already too-long post much longer, but both Christian institutions and individuals are implicated. True story: a guy I know’s mother complains all the time about the failures of the churches (not that she attends one faithfully), and especially loves to rail about how “they don’t teach the Ten Commandments in our churches anymore.” He said to her one day, “Mom, what are the Ten Commandments anyway?” She managed to come up with three, maybe four.

And from a certain way of looking at it, the fact that cultural Christianity of the sort in which many of us were raised is dying is not a bad thing. Russell Moore says:

Bible Belt near-Christianity is teetering. I say let it fall. For much of the twentieth century, especially in the South and parts of the Midwest, one had to at least claim to be a Christian to be “normal.” During the Cold War, that meant distinguishing oneself from atheistic Communism. At other times, it has meant seeing churchgoing as a way to be seen as a good parent, a good neighbor, and a regular person. It took courage to be an atheist, because explicit unbelief meant social marginalization. Rising rates of secularization, along with individualism, means that those days are over—and good riddance to them.

Again, this means some bad things for the American social compact. In the Bible Belt of, say, the 1940s, there were people who didn’t, for example, divorce, even though they wanted out of their marriages. In many of these cases, the motive wasn’t obedience to Jesus’ command on marriage but instead because they knew that a divorce would marginalize them from their communities. In that sense, their “traditional family values” were motivated by the same thing that motivated the religious leaders who rejected Jesus—fear of being “put out of the synagogue.” Now, to be sure, that kept some children in intact families. But that’s hardly revival.

Secularization in America means that we have fewer incognito atheists. Those who don’t believe can say so—and still find spouses, get jobs, volunteer with the PTA, and even run for office. This is good news because the kind of “Christianity” that is a means to an end—even if that end is “traditional family values”—is what J. Gresham Machen rightly called “liberalism,” and it is an entirely different religion from the apostolic faith handed down by Jesus Christ.

I agree with this, mostly, but I can’t help worrying about the kind of world that we will inhabit when the absence of general, nominal Christianity makes people feel unrestrained in the face of evil passions, or uninspired to act on good ones. Like it or not, that’s the world we are in now, and rapidly heading toward.

So, to return to the beginning of this post: the churches that substitute the Social Gospel for any kind of real Christianity are plainly dying, because they offer nothing but sentimental humanitarianism. The death of Christianity in the West will be ruled a suicide, for sure.

What about those Christians who do not want to follow their leaders into senescence and dissipation? It’s these Christians I want to speak for, and speak to, with the Benedict Option. The first and most important thing we have to do, per Prof. Wilken, is to start telling ourselves our own story again, and believing it, and living that story out in tangible ways.

What does this mean? I am going to spend the first half of 2017 exploring that in-depth. Your input is requested. Specifically, what would you say to those troubled German Lutherans who, upon hearing the crap sermon, “looked around with annoyed faces but continue”? According to what the German-American correspondent says, they are all elderly. Their children and grandchildren aren’t even there to look annoyed, much less continue. What should they do? And what should much younger Christians who don’t want to be in their place one day, or to see their children in such a place, now do?

Keep in mind that we didn’t get here overnight, but it’s also true that the world we are in today in the West is very different in terms of what you might call the “imagination horizon” than it was well within living memory.

UPDATE: On the previous thread, the (native-born) “German Reader” (his nom de blog) responded to John Carter’s comment by saying that he was baptized in the state Lutheran church, but has stopped going and is going to officially renounce it next year. German Reader writes:

I don’t think the Lutheran church has much of a future in Germany, it’s moribund, and the church leadership is in denial about this. Its membership numbers may still look impressive but that’s just a left-over from a time when almost everyone belonged to a church…my generation will be the last one in which that was the case (and I know people my age who were never baptized and had even less exposure to Christianity that myself as children). In 20-30 years time when its older members have died off there won’t be much left of the Lutheran Church. And considering how that church has become little more than the (somewhat) spiritual arm of the Greens and Social Democrats, I can’t say I feel really sorry about this.

Interesting. You have some vocal Americans saying that the church here is the Republican Party at prayer, which is why they have no interest in it.

UPDATE.2: Erin Manning gets it. Her comment:

Having read all the comments, I think that most are still misreading Rod when he says, “I agree with this, mostly, but I can’t help worrying about the kind of world that we will inhabit when the absence of general, nominal Christianity makes people feel unrestrained in the face of evil passions, or uninspired to act on good ones. Like it or not, that’s the world we are in now, and rapidly heading toward.”

Of course atheists and Buddhists and Confucians and pagans and agnostics (etc.) can be good, decent people. The question is not, “Can any faith tradition or belief system other than Christianity foster solid virtues and ethical behaviors?” Rather, the question is, “What happens when the predominant faith tradition or belief system of a culture collapses and is not replaced by any new, coherent system?”

History is full of examples of that sort of thing: the collapse of a culture or civilization’s religious/philosophical/moral worldview, followed (often) by the collapse of that culture or civilization altogether, and the rush by some new culture to fill the vacuum the dying culture is leaving behind. I sometimes think that people today think of a sort of nihilistic material secularism as the “normal default” state of a culture and they presume that America, after a couple centuries of rather artificial, weak, lip-service Christianity, is returning to that natural state. However, most cultures don’t survive for long without a “cultus,” a set of unifying beliefs that not only govern life but are even worth dying for–and few people are willing either to order their lives around, or to die to preserve, a nihilistic material secularism.

So what happens when the last vestiges of a cultural Christianity die out in a country that has taken that Christianity (whether it is a good kind or not) pretty much for granted?

Well, as a concrete example, I know someone who works in a doctor’s office in the South, and her co-workers are (many of them) the kind of Southern women who a generation ago would have been very connected to their church communities and very well versed in the ideals of Christian morality and ethics (though, of course, knowing the good and choosing to do it have always been two different things). My friend relayed a conversation once that had to do with dating and relationships. Her coworker said, in effect, “Dating is hard for me because I’m a good girl. I don’t believe in sleeping with anybody I’m not presently dating. I don’t judge my friends who don’t always keep that rule, but for me personally it just doesn’t feel right to sleep with somebody when I’m dating somebody else. If I want to sleep with the other guy, I always break up with my boyfriend first. My friends may make fun of me for being so virtuous, but I have to keep the rules that are good for me.”

Now, from a Christian missionary perspective one could say that at least this young lady has *some* idea, however erroneously formed, of right and wrong and of sexual morality. But, honestly: being a virtuous woman means you break up with your current boyfriend when you meet somebody hotter whose bed you want to share? It’s not a form of sexual ethics any major belief system throughout human history would recognize, and it’s also not, as our ancestors would have known how to explain, the sort of thing that leads to human flourishing, unless your idea of human flourishing is a whole lot of lower middle class women someday in their forties and fifties who have a kid or two in or out of temporary wedlock with long-gone fathers, a hand-to-mouth financial existence, and not much hope for a happy old age–to say nothing of the likely futures of their children. When a handful of women in a community choose to live this way, the community can absorb their dysfunction. But what happens when the whole community is founded around the idea that this isn’t dysfunction, that it is a normal and healthy and empowering way for women to arrange their lives?

Sure, the modern age didn’t invent stupid women or promiscuity. The modern age also didn’t invent cheating college students (and professors who help them cheat), lying on one’s taxes, employers cheating employees, employees lying to get extra time off or helping themselves to company goods or materials, a justice system that punishes the poor disproportionately as compared to the rich, and so on. What has changed is the notion that most of these things aren’t really wrong, that it’s all a matter of perspective, and that the only real moral law is doing whatever feels is right or whatever will advance one’s own interests (even if other people get hurt in the process). And even that has changed primarily as a matter of degree–because there have always been people who have thought this way in America, but before now they had to pretend they didn’t think so precisely because that weak cultural Christianity, as embodied by their friends and neighbors, was watching.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.