Shocking Numbers for Benedict Option

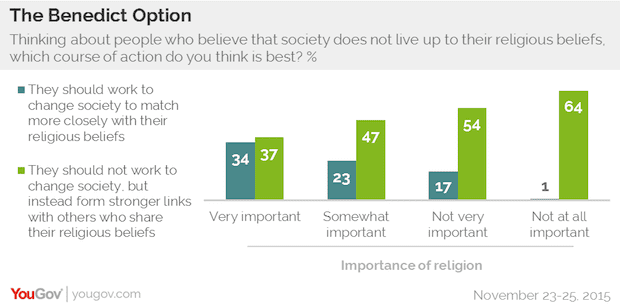

Here is some striking news, from YouGov.com:

Over recent decades, particularly the past ten years, the United States has undergone a wave of social change to become a more liberal and secular society. The vast majority of Americans (67%) say that the United States has become less religious over the past 25 years, and with recent victories on same-sex marriage and other issues social conservatives have faced a string of political defeats. These defeats and the apparent reality of an America where the ‘majority’ is no longer ‘moral’ are forcing social conservatives and religious leaders to reconsider their role in society. Conservative intellectual Rod Dreher has gained an increasingly large following in arguing for the ‘Benedict Option’, saying that in today’s world Christians should withdraw from public activism and seek to preserve their morality by strengthening their ties and forming a robust Christian sub-culture.

Here are the numbers:

Mind you, that’s something of a false choice. I don’t think it’s an either-or, but rather a matter of emphasis. I see nothing wrong with Christians working to change society, but I believe their (our) prime emphasis should be on forming stronger internal links. Here’s the Benedict Option FAQ if you’d like a clearer idea of what I’m talking about.

This result shocked me. I would have guessed the number of BenOp supporters among the most committed Christians to be 20%, tops. Not sure why that number, but that was what my gut told me. Turns out it’s nearly double — and slightly more than the Christians who favor doing what we’ve always done, but accepting that we’ve lost on SSM (that is, the Wilberforce Option). Twenty-nine percent are undecided, and therefore persuadable.

Bottom line: This poll is the first solid evidence I’ve seen from a non-partisan source documenting that the Benedict Option is something real, and important.

I also find it interesting that the term “Benedict Option” has now crossed over into the mainstream. When a secular polling firm starts using it, you know that it’s not just a concept from the margins.

I read a couple of pieces over the weekend that offered insight into the need for the Benedict Option, though neither piece uses the phrase. The first is a very strong blog post by Dustin Messer, a Reformed Christian who lays into the weakness of trendy, megachurch Christianity. It begins like this:

Several days ago, Kent Dobson, successor at Rob Bell’s famous Mars Hill Bible Church, stepped down as teaching pastor. He opened his announcement/sermon by reading the Scriptural story which gives name to the church, the account at Mars Hill. Dobson says when he first came to Mars Hill, he was animated by Paul’s example of cultural engagement. Paul quoted the poets of the people; he spoke their language. Dobson said he understood Paul to be preaching a traditional gospel message but using different, more relevant, packaging.

Likewise, he said the church was meant to have the same gospel but deliver the message in a more hip way. Specifically, he wanted a “cool church” with “cooler shoes” than the traditional church down the road. However, Dobson said he not only began to question the packaging of traditional “church,” but also the message – the gospel. To fully understand his evolution he says, “you’ll have to read my memoirs.” The CliffsNotes version, for those of us who can’t wait, goes thusly:

“I have always been and I’m still drawn to the very edges of religion and faith and God. I’ve said a few times that I don’t even know if we know what we mean by God anymore. That’s the edges of faith. That’s the thing that pulls me. I’m not really drawn to the center. I’m not drawn to the orthodox or the mainstream or the status quo… I’m always wandering out to the edge and beyond.”

Messer hits hard and true:

To his church, he paints himself like a modern-day Ferdinand Magellan, ready to explorer the great spiritual unknown. Motivated by nothing but curiosity and bravery, he’s boldly setting his sails toward the choppy waters which stand between what is and what could be. This is the point at which I take issue. When was the last time Pastor Dobson talked with someone on a college campus, in a gym, or in a coffee shop? Does he really think the “open” and “inclusive” vision he’s casting is novel? Is the “status quo” really Christian orthodoxy among Dobson’s peers? As a young, fit, white, upper-middle class male, Dobson’s sermon is not a rebellion to his culture. It’s a product of his culture. The mystery and romance he attempts to conjure around his spiritual evolution is laughable to anyone with a television. He’s not moving forward into the unknown; he’s sitting perfectly still in the safe, cozy space where Oprah is queen, tolerance is the law, and anyone with a firm opinion on just about anything is suspect.

And:

These days, the real adventurers are those who set sail for the risky land of Christian orthodoxy. The real brave men and women are those who consistently go to church, observe the sacraments, hear the word, and submit themselves to the discipline of the church. In an age of autonomy, it’s those who subject their thoughts, behaviors, and passions to an exclusive Sovereign that are the brave few. Those may not be the memoirs we’re interested in today, but they’ll be the ones that last tomorrow.

Preach it, brother. Read the whole thing. This is a time of testing, of winnowing. The churches of the future in America and Europe will be smaller, but they will be stronger, because being a Christian is going to cost something. Russell Moore, as you probably know, is optimistic about the future of the faith, because these post-Christian times are finally freeing the churches of the illusions of civic Christianity. More and more these days I’m hearing from friends and readers — conservative Christians — who tell me how frustrated and concerned they are with the lack of substance in their churches. Not long ago, I was talking about this stuff with a couple of folks who are part of a conservative denomination, and told them they’re lucky to be where they are.

Au contraire, they said, explaining that however conservative their denomination may be theologically, where they live, the church itself is all about emotional uplift. They are especially worried that their kids are being acculturated into a form of Christianity that may be conservative in principle, but is in practice, at the local level, is nothing more than Moralistic Therapeutic Deism.

They are right to be concerned.

In October, I wrote a piece framing the Benedict Option as key in the struggle of Christian memory against forgetting. In it, I talked about a book called How Societies Remember, by a social anthropologist called Paul Connerton. Excerpt from my blog post:

Connerton says that modernity is a condition of deliberate forgetting, of choosing to deny the power of the past to affect our actions in the present, so as to create a new condition of existence marked by the individual’s freedom of choice. Capitalism requires this deliberate forgetting, and facilitates it, and rites we invent in modern times “are palliative measures, façades erected to screen off the full implications of this vast worldwide clearing operation.” Here is the core [of Connerton’s theory]:

“Under the conditions of modernity the celebration of recurrence can never be anything more than a compensatory strategy, because the principle of modernity itself denies the idea of life as a structure of celebrated recurrence. It denies credence to the thought that the life of the individual or a community either can or should derive its value from the acts of consciously performed recall, from the reliving of the prototypical. Although the process of modernisation does indeed generate invented rituals as compensatory devices, the logic of modernisation erodes those conditions which make acts of ritual re-enactment, of recapitulative imitation, imaginatively possible and persuasive. For the essence of modernity is economic development, the vast transformation of society precipitated by the emergence of the capitalist world market. And capital accumulation, the ceaseless expansion of the commodity form through the market, requires the constant revolutionising of production, the ceaseless transformation of the innovative into the obsolescent. The clothes people wear, the machines they operate, the workers who service the machines, the neighborhoods they live in — all are constructed today to be dismantled tomorrow, so that they can be replaced or recycled. Integral to the accumulation of capital is the repeated intentional destruction of the built environment. Integral too is the transformation of all signs of cohesion into rapidly changing fashions of costume, language and practice. This temporality of the market and of the commodities that circulate through it generates an experience of time as quantitative and as flowing in a single direction, an experience in which each moment is different from the other by virtue of coming next, situated in a chronological succession of old and new, earlier and later. The temporality of the market thus denies the possibility that there might co-exist qualitatively distinguishable times, a profane time and a sacred time, neither of which is reducible to the other. The operation of this system brings about a massive withdrawal of credence in the possibility that there might exist forms of life that are exemplary because prototypical. The logic of capital tends to deny the capacity any longer to imagine life as a structure of exemplary recurrence.”

What does this mean? He’s telling us that in modernity, the market is our god. It conditions what we imagine to be possible. We can’t dream that life should be ordered by rituals that bound and define our experience, and link it to the past, to a sacred order. There is no sacred order; there is only the here and now, the tangible. The world exists to be remade to fit our desires. There are no ways of living that we should conform our lives to, no stories that tell us how we should live. When Connerton says that in modernity, and under capitalism, we can hardly “imagine life as a structure of exemplary recurrence,” he’s saying that we can no longer easily believe that we should live according to set patterns of thought and action because they conform to eternal truths.

In my post, I said that you have right-wing versions of this, and left-wing versions of this, but they both function to sever us from historical iterations of the Christian faith. Ultimately, Christianity cannot help but dissolve in the Zeitgeist. Rootless, we will be swept away by the overwhelming currents of modernity. More:

It occurred to me while reading this that the most dangerous enemy we face is not the State, and what it might yet do to individual Christians and their institutions and businesses. The most lethal foe is the Empire of Amnesia, which induces us at every turn to forget who we are, to forget who God is, and to forget what He wants from us. The Empire of Amnesia does not force us to forget our sacred Story as the Soviet empire did to believers; rather, it entices us to forget so we can set free our passions. So we can have our best life now. So we can be as gods. And as Ross Douthat once wrote, “no conservative dream, in the 400 years from Francis Bacon until now, has proven strong enough to stand in its way.”

This is the mission of the Benedict Option: to turn away from the Empire of Amnesia, to build “new forms of community” that can offer sustained resistance to it, and to give ourselves, our children, and our communities resilience in the face of its power, and ultimately to create, over time, the conditions for the resurrection of Christian civilization.

Now, Kevin Flatt, an Evangelical and academic historian, writes powerfully about “lessons for an amnesiac society.” From his essay:

Civilizational amnesia is not only a condition of professional historians or intellectual life, however. It also forms and deforms our patterns of institutional life together— our social architecture. This is perhaps obvious in the realm of democratic politics, where few people apart from political scientists look much further back than a few election cycles, and in the business world, where the passwords of the hour are entrepreneurship, rebranding, and disruptive innovation. Amnesia’s influence, however, is also felt in more subtle ways right across the variegated institutions of civil society.

Take, for example, our churches. (I draw examples from North American evangelicalism both because that is what I know best and because, notwithstanding its considerable virtues, it may be the form of Christianity most susceptible to institutional amnesia.) Over the past thirty years an emphasis on novelty has come to dominate our worship services, with the longevity of the latest worship song continually dwindling toward the brief shelf life of a hit on the Top-40 charts. Every decade or so a revolutionary new “model” of church growth and vitality—the Willow Creek model, the Purpose-Driven Church, the Simple Church— sweeps away existing patterns of congregational life. Indeed, in recent years hosts of evangelicals have been led away by supposedly cutting-edge “emerging” or “postevangelical” movements that would immediately have been recognized by their grandparents as barely warmed over Protestant liberalism. Even churches with a relatively robust inherited sense of historical continuity have been drawn into the current of relentless change, novelty, and reinvention.

He faults North American Evangelicalism, but I tell you from experience, the richness of liturgy, teaching, and tradition present in Catholicism and Orthodoxy are no vaccine against this rootlessness. The form of worship may be stable, but if church leaders and congregations don’t fill those forms with knowledge, spiritual substance, and engagement, the forms will be useless. For example, I’ve had Catholic university professors tell me that their classes are full of graduates of Catholic high schools who arrive knowing little or nothing about their faith. This is not an Evangelical problem, a Catholic problem, an Orthodox problem: it is an American Christian problem.

A bit more from Flatt:

The restless tide of late modern amnesia thus continually washes against our institutions and, unless they possess a certain solidity, erodes their foundations. For those of us who care about the health of our social architecture, how do we resist this erosion? And, just as importantly, how do we go beyond mere erosion resistance—which can too easily degenerate into curmudgeonly stubbornness— to the constructive task of building resilient institutions that remember forward, harnessing the memory of the past for the visions of the future?

That is a central question for the Benedict Option. Read the whole Flatt essay.

Do I think 37 percent of the most committed Christians in the country think about cultural theory, religious history, and the deep crisis of modernity? No, I do not. I don’t think any but a fraction of those people have ever heard the term “Benedict Option.” But they will. And they know the most important thing right now, in their hearts: that we can’t keep living this way. That these are not normal times. That the center is not holding. That status quo Christianity is doomed. In the first chapter of my upcoming book on the Benedict Option, I write:

Being faithful in a post-Christian world is going to cost us something. Cultural Christianity is dying, and nearly dead. There is no conservative arcadia in which to make our retreat. The day is coming, and coming fast, when there are no more effective arguments to be made in the public square. The only arguments remaining to us will be the witness of our lives. We are going to have to become a church that knows how to suffer – and how to suffer, as the early church did, with a mysterious kind of joy. We are going to have to hear Jesus’s words in the Beatitudes – “blessed are you when they persecute you” – and believe them, and live them.

One Christian professor, deeply closeted as a believer at an elite American law school, told me that “Alasdair MacIntyre is right.” Christians should “surrender political hope” – that is, the expectation that politics can save us, or even protect us – recognize that culture is far more important than politics, and get busy pioneering the Benedict Option. There is no time to waste. There will be no “taking back our country”; the country is lost to Christianity for the foreseeable future. Voting Republican is at best a stalling tactic to enable Christians to establish institutions and build networks for the long resistance ahead.

I am very encouraged by the evidence of this YouGov poll that there are so many committed Christians in this country who are open to the Benedict Option. This is not going to be easy, laying the groundwork for this project, but the time is right, and people are far more ready than even I had thought.

Below is an image I shot in the piazza of Norcia, the Umbrian hometown of St. Benedict. That is a statue depicting him, and behind him is the basilica and the monastery. Be of good cheer! It is a place of light in this present darkness.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.