Remembering Slavery At Whitney

We have old friends visiting this week from Europe. I encouraged them to go to Rosedown Plantation, in St. Francisville, which is one of the grandest and best preserved plantations in the South. It really is a wonder to behold. But Julie and I also suggested that they get the other side of the story by going to Whitney Plantation, down the river in St. John the Baptist Parish.

Whitney Plantation is America’s only museum of slavery. John Cummings, a (white) New Orleans lawyer, bought the antebellum home and property in 1998, and spent $8 million restoring it. It has been open for less than two years. From a newspaper story:

“Who in the hell built this house?” Cummings thundered… . “Who built this son of a bitch? We have to own our history.”

Slaves did. Cummings is passionate about telling the story of what slavery was. South Louisiana is full of plantations, some of which have started to be more honest and open about slavery. But none are dedicated only to telling the story of the enslaved Africans who worked those sugar cane and indigo fields.

My family has never been to Whitney. We joined our friends there this afternoon. It was unforgettable. I mean that. As I sit here after midnight on Wednesday, writing this, I can hear my son Lucas and his Franco-Dutch friend Léon lying on air mattresses in the darkened living room, talking about the lives of the slaves. It made a huge impression on them, this plantation.

The tour begins in the Antioch Baptist Church, a 19th-century African-American church building donated by the congregation, which was founded by freed slaves, and which gave their original church building to Whitney Plantation when they built a new chapel. Inside the restored church, sculptor Woodrow Nash created clay life-size images of actual Louisiana slave children whose stories about their childhoods in bondage were collected in 1940 by the Works Progress Administration. Here is a view:

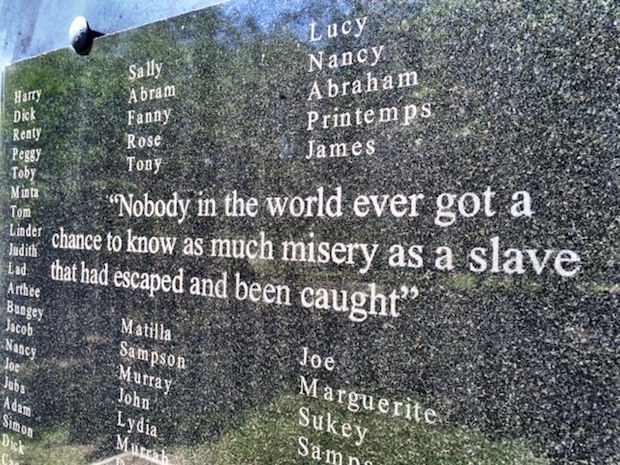

Behind the church there is the “Wall Of Honor,” which is actually several granite walls, upon which are inscribed the names of every slave who ever lived, labored, and suffered on Whitney Plantation, as far as historians are able to document from the records. They only have one name, because they were not accorded the dignity of surnames. Scattered throughout the list of names are quotes from actual slave testimonies:

The glare of the afternoon sun prevented me from photographing the most harrowing passages, including a couple from freed slaves recalling savage beatings they endured as children — one from a woman who was beaten bloody for stealing a biscuit, because she was hungry.

This clip from a Smithsonian magazine story gives you more details about the Wall, the nearby Garden of Angels, and other buildings:

But interspersed throughout is something more telling of the slave experience than a last name: testimonials to the brutality doled out by plantation overseers. “They took and gave him 100 lashes with the cat of ninety-nine tails,” wrote Dora Franks of her uncle Alf, whose crime was a romantic rendezvous off the property one night. “His back was somethin awful, but they put him in the field to work while the blood was still runnin’.” Another story ends with a single terrifying phrase: “Dey buried him alive!” As the tour passes massive bronze sugar kettles, the slave quarters and the kitchens, the narrative of persecution is a relentless wave of nauseating statistics. Some 2,200 children died enslaved in the home parish of the plantation between 1820 and 1860; infant mortality was grotesquely common. Some 100 slaves were forced to work around the clock during the short autumn harvest season to keep the massive sugar kettles going. Slaves laboring in the dark routinely sustained third-degree burns and lost limbs, although this rarely ended their servitude. Amputations were frequent; punishment by the whip common. A trip to the Big House — at one time called “one of the most interesting in the entire South” by the Department of the Interior — reveals incredible architecture and design, including rare murals by Italian artist Domenico Canova. But the elegant front portico looks out toward the river, turning its back on the daily parade of torture and terror just steps away from the backdoor.

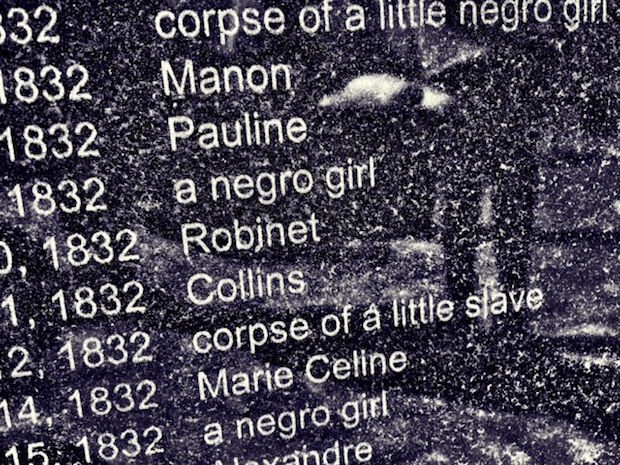

Here’s a photo I took in the Garden of Angels:

That’s how the deaths of these children were recorded, verbatim. “corpse of a little slave.” “a negro girl”. Human beings. Children, their names known only to their mothers.

“My God, what a contrast to what we saw this morning,” said one of our visitors, referring to Rosedown. Yes, it is. Julie and I were so grateful that we had the opportunity to visit Whitney Plantation. Living here in the Deep South, even though some plantation houses open to the public are trying to do better by historical honesty, none, to my knowledge, remotely approach the thoroughness of Whitney Plantation. It is very hard to think of the beauty and glory of the Old South when confronted by the names of human beings, and the stories of what they endured at the hands of white society.

Here’s the thing that is so hard to hold in your mind: there was beauty in the son of a bitch. Look at this fresco image left inside the Big House by an Italian artist:

How can people capable of appreciating the beauty of that image, and allowing it to grace their domestic life, have also enslaved and tortured human beings? It is a naive question, I guess, but it is also the question we have to ask. The men and women who enslaved the Africans were not monsters, though they did monstrous things. They were people like us. As a small boy, I heard some older white people claim that the slaves loved their masters, and that the horrors of slavery were exaggerated.

The lie has to be countered, again and again. I told my children that the Confederate battle flag flew over soldiers — including our own ancestors — who fought to preserve the social order that enslaved Africans. That’s not all that social order meant, but it did mean that, and the stain cannot be erased. Nor should it.

If you are coming down to South Louisiana, please consider making the Whitney Plantation part of your trip. It is a profound experience that left some of our group near tears. To you readers who are coming to the Walker Percy Weekend — some tickets are still available — I hope you’ll add an extra day to see Rosedown in the morning, and Whitney in the afternoon. It will add such dimension to your understanding of Southern history, and American history, and the history of the human race.

One last thing. As some of you know, I worked with the African-American actor Wendell Pierce in the writing of his memoir, The Wind In The Reeds. Wendell’s ancestors on his mother’s side come from this area (specifically, from a neighboring parish). His great-grandfather was a slave child named Aristile, whose early memories include watching Union soldiers marching along the levee during the Civil War. In the book, Wendell tells the story of his family’s history up from slavery.

On the Whitney tour, our guide, Adina, explained how freed slaves were still held in a kind of bondage on plantations through the sharecropping system. They were only allowed to buy goods through the plantation store, which, of course, jacked up prices and kept the sharecroppers in debt bondage. I told the story, from Wendell’s book, about Father Harry Maloney, a white Catholic priest of the Josephite order who came to serve the black Catholics of Ascension Parish, where Wendell’s grandparents lived. As the story, which came from Wendell’s Uncle Lloyd, goes, Father Maloney used the power of his white skin and Roman collar in the heavily Catholic area to defy the racist power structure on behalf of his flock. Father Maloney broke the power of the plantation stores by running food drives, then distributing the goods to sharecroppers, so they didn’t have to depend on the exploiters.

“I grew up here, and I’ve heard of him!” Adina said. Later, we told more Father Maloney stories, including one about how he started a bus service to the Avondale Shipyards in New Orleans, so black men who had no cars could get down there to take good jobs, and thereby escape the miserable sharecropping life. Adina told me that bus is still running today, over 60 years later.

I tell you about the selfless deeds of that righteous white Catholic priest in part because of this I saw on the wall as we left the Visitor’s Center:

History is impossibly complicated, morally and otherwise. A few weeks ago, I gave a talk at my local library about The Wind In The Reeds, and the things I learned about my own state and its racial history from working with Wendell. I said at the end that it made me think, and think hard, about how in our town every spring, we celebrate the 19th-century heritage of this historic and beautiful countryside, but we avert our collective gaze from the fact that in the period and the society we celebrate, the ancestors of about half the people in the parish today were held in bondage. It’s not right to tell only a partial truth, for it might as well not be the truth at all, I said.

Nowadays, the New Orleans city government is attempting to remove statues and memorials to Confederate figures, like Robert E. Lee atop Lee Circle. I think this is wrong, and in my library talk, I said that even though I think the Confederacy fought to preserve an evil institution, we should not pull down the statue of the Confederate soldier that stands on the courthouse lawn in our town. But we should add to the courthouse lawn a memorial to the slaves of our parish, or even better, a statue of the Rev. Joseph Carter, who stood down a foul-mouthed white mob on October 17, 1963, to become the first black man to register to vote here in 61 years.

It’s time we talked openly about this, and did right by history. Going to Whitney Plantation on Wednesday made me feel even more strongly that the way to confront history is not by tearing down statues or razing plantations that stand as monuments to those things, but rather to erect memorials and museums like Whitney Plantation, to broaden and deepen awareness of the moral and historical record, and the commemoration of the world the slaves made.

Every former slave state needs to have a Whitney Plantation. I guess they would first have to have a John Cummings, who has served the people of Louisiana, black and white alike, well with his labor and his ardor for justice. Here, finally, is a CBS report on Whitney Plantation. This will have to do until you can see it yourself. Bring your children.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.