Reading Dante While Protestant

Karen Swallow Prior, whose glasses are cooler than mine, if you can believe it (see for yourself!), has a lovely reflection up today on The Gospel Coalition website, talking about what Protestants can learn from going on the journey with Dante through The Divine Comedy. Excerpts:

What might medieval Catholic poet Dante Alighieri teach Protestants today? A lot, actually.

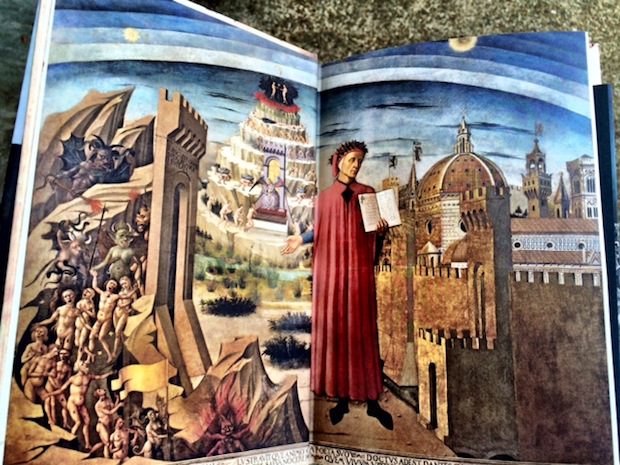

Dante’s masterpiece, The Divine Comedy, has been rightly called “one of the essential books of mankind.” Hundreds of extant early manuscripts and printed editions attest to the popularity of the work in its own age. Its treatment by the word’s great artists, musicians, and writers over the past 700 centuries proves its continued lure. It has been translated into English countless times and featured regularly on lists of the world’s best books and best poetry. Earlier this year—the 750th anniversary of Dante’s birth—Rod Dreher published a marvelous book How Dante Can Save Your Life [review], meditating on the power of the poem to change his life.

While The Divine Comedy most clearly reflects the Catholic faith of the poet and his medieval world, it hints at some principles the Reformation would bring to bear on the church two centuries later.

“A marvelous book!” — Karen Swallow Prior. Thanks, ma’am. More:

After descending all the way to the center of the earth where hell is housed, Dante proceeds out of it simply by stepping forward. He emerges on the island of Mount Purgatory and begins an ascent that will eventually take him to heaven. While purgatory is clearly rooted in Roman Catholic doctrine, Dante depicts it as the kind of purgation of sins that slightly resembles the Protestant understanding of sanctification. In Purgatorio, the pilgrim encounters repentant sinners in the process of shedding their defects of character and shortcomings so as to achieve a purified state befitting heaven. The circles of hell are paralleled by seven terraces leading upward. Sins are arranged in the reverse order of hell, with the graver sins of the will encountered first followed by those of the flesh: pride, envy, wrath, sloth, avarice, gluttony, lust.

Virgil, Dante’s guide, explains that all actions stem from either natural or spiritual love. Perversion of love leads to the sins from which one must be cleansed. Here, he echoes Augustine on sin as disordered love, a theme recently revived by Tim Keller. Upon reaching the last level of purgatory, Virgil declares: “Your will is free.” The greatest revelation of Dante’s journey comes when he realizes that all shortcomings are shortcomings of love.

Read the whole thing. You don’t have to be a Catholic to gain so much practical spiritual wisdom from reading Dante. I wrote my book for ordinary people, Catholic and non-Catholic, Christians but also those who don’t necessarily affirm the faith, to describe how the penitential journey into the Self, on the winding path to God, is a pilgrimage we all can and must take. That was the thing that really struck me about the Commedia: how acute was Dante’s spiritual and psychological insight, and how accessible and relevant it was (see here, for example). This Italian Catholic poet of the High Middle Ages just might know you and all the strategies you use to hide from God better than you know yourself and your own self-deceptive ways. That was true for me.

That is one of Karen Swallow Prior’s points in her essay: that by writing his poem in the vernacular language (versus Latin, the scholar’s language), Dante brought his divine message directly to the people, because he wanted to reach ordinary people.

If you are a Protestant who has read either the Commedia or How Dante Can Save Your Life, I would love to hear from you about what you learned.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.