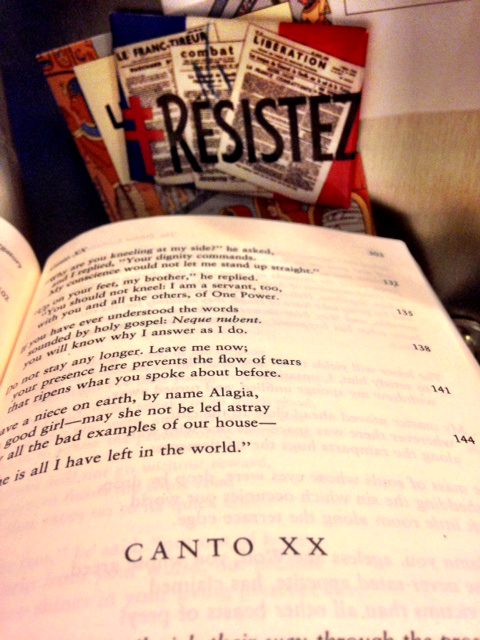

Purgatorio, Canto XX

Canto XX is a highly political canto. There’s barely room to move on the terrace of Greed, given the vast number of penitents working off the effects of this sin. The sight of all those greedy souls infuriates Dante:

Canto XX is a highly political canto. There’s barely room to move on the terrace of Greed, given the vast number of penitents working off the effects of this sin. The sight of all those greedy souls infuriates Dante:

God damn you, ageless She-Wolf, you whose greed,

whose never-sated appetite, has claimed

more victims than all other beasts of prey!

You heavens, whose revolutions, some men think,

determine human fate — when will he come,

he before whom that beast shall have to flee?

What Dante is up to here is blaming Greed — greed for power — for the political violence that has torn Italy apart in his lifetime. Remember, he fought in the wars between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines, and was later exiled when fighting broke out between two factions of Guelphs. The Guelph-Ghibelline wars were proxy battles between forces loyal to the Holy Roman Emperor, and forces loyal to the papacy. In this seemingly endless struggle, the papacy allied itself with French kings. In real life, Dante abhorred French meddling in Italian politics as much as he despised papal machinations in the affairs of state.

On this terrace, the pilgrim meets Hugh Capet, founder of the Capetian royal line in France, which produced 11 kings in unbroken succession. The Capetians made France a great power in Europe, but here on the terrace of Greed, Hugh stands shouting praise for the holy poverty of the Virgin Mary, of the noble asceticism of the incorruptible Roman statesman Fabricius, and of the generosity of St. Nicholas of Myra, who gave gold coins to prevent a poor man from selling his daughters into prostitution.

In Purgatory, Hugh sees life in the world very differently. He has no praise for his illustrious descendants, only condemnation. He calls his family line “that malignant tree which overshadows all of Christendom.” The former French monarch says that the greed of his descendants for wealth and power caused war to break out all over. They even ended by turning on their own family members, and, worst of all, made common cause with the Colonna family to invade Pope Boniface VIII’s villa, and abuse him.

This was a scandalous historical event. Boniface hated the Colonnas, his rivals in church politics, so much that he declared that fighting them was the equivalent of holy war. The Colonnas made a deal with a minister of Philip the Fair, the French king excommunicated by Boniface, to invade Boniface’s residence outside of Rome and rough him up. Shortly after this event, Boniface, who was elderly, died from the injuries (possibly simply psychological) suffered in it.

Now, Dante Alighieri despised Boniface, blaming him for corrupting the Church with his political scheming; he even prepared a place in Hell for Boniface in his poem. But Dante was, above all, a loyal man of the Church. In Purgatorio, Dante likens the abuse of the man he viewed as the Vicar of Christ to a re-enactment of the Crucifixion. Prue Shaw, in her recently published Reading Dante, observes:

The energy of the moral revulsion is Dante’s own, but here, unexpectedly, the eloquence is in defence of Boniface, the man he loathed. The distinction between office and incumbent is fundamental. Boniface is a despicable and evil man, but the office of pope commands respect. Once again Dante has structured the narrative in dramatic terms; once again, we are witnessing self-recrimination. Just as it is a pope who condemns other popes in Inferno XIX, so here is it their own ancestor who condemns the degenerate descendants of the Capetian dynasty for their shameful crimes, crimes that have had such catastrophic consequences for Italy and Florence.

In these postimperial times, it’s hard for us to feel the force of Dante’s use of French expansionism as an illustration of Greed. It is an example, though, of the enormous public consequences of a private vice. In Dante’s view, the greed of the French monarchy helped destroy the peace of Italy, and even led to an unspeakable sacrilege. Dante’s longing for a figure who will make the She-Wolf of greed flee is his aspiration for a political savior to bring peace, order, and good government to chaos-stricken Italy.

Reading this canto, though, I was reminded of this story from yesterday’s New York Post, about what the suicide of the jet-setter L’Wren Scott says about wealth and fame. Excerpt:

To look at her carefully curated Instagram feed, designer L’Wren Scott was a 1-percenter, a gold-plated member of the international elite: There she was on vacation in India with boyfriend Mick Jagger; at his retreat on the island of Mustique; about to board a chartered helicopter; lounging poolside in gold jewelry and designer sunglasses; stretched out on a private plane, using her $5,000 Louis Vuitton handbag as a footrest.

“I always say luxury is a state of mind,” Scott told The Sunday Times of London last November. “Because for me, it really is. It’s legroom, it’s a beautiful view, it’s great food at a great restaurant you’ve discovered because you obsessively read Zagat, as I do.”

And then, last Monday, she committed suicide, hanging herself in a $5.6 million Chelsea apartment that likely did not belong to her. Within hours, Scott’s life was revealed to have become an elaborate facade — her business at least $6 million in debt, her fashion-world friends and celebrity clientele unaware of her despair.

“Ironically, last week I said to three different people, ‘I wish I had her life, look at her life — she’s always somewhere fabulous and fancy,’ ” stylist Philip Bloch told WWD. “You think, here’s someone who has it all. You just never know.”

The story goes on to say that a number of New York A-listers fake their lives, living far above their means to stay on top of the world. But it all means nothing in the light of eternity, except as a bringer of death. Remember the Siren from Canto XIX, who hid her foulness and stinking belly beneath a veil of sensual allure. Think of all the wealthy families who have had no end of sorrow because their great riches corrupted their souls.

At the end of Canto XX, the mountain shakes violently and a cry goes up: Gloria in excelsis Deo! Glory to God in the highest?

What just happened? We’ll find out tomorrow.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.