Purgatorio, Canto XII

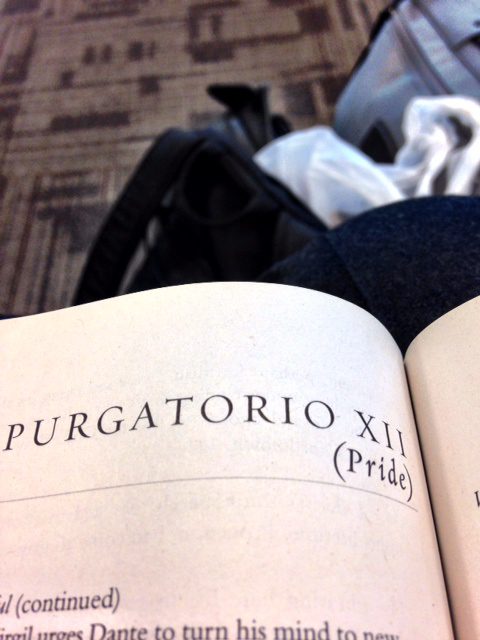

Beyond the pages of the Purgatorio (Hollander version; who took my Musa?) are my bags. I’m sitting in the Baton Rouge airport; my flight to Dallas is delayed. I’m already too late to make my connection to Grand Rapids. I hope I can get rescheduled before the frozen boudin links in that white plastic bag you see there melt.

Beyond the pages of the Purgatorio (Hollander version; who took my Musa?) are my bags. I’m sitting in the Baton Rouge airport; my flight to Dallas is delayed. I’m already too late to make my connection to Grand Rapids. I hope I can get rescheduled before the frozen boudin links in that white plastic bag you see there melt.

So, let’s talk about Canto XII until the flight leaves, shall we? The canto begins with Dante still deeply in conversation with Oderisi. Virgil urges Dante to move on — remember, Dante has places to go. He mustn’t linger.

I set out, following gladly

in my master’s steps, and our easy stride

made clear how light we felt.

Yes, exactly — Dante has made tremendous spiritual progress after repenting of his Pride in the last canto. Robert Hollander says this is the greatest leap of spiritual progress the pilgrim makes in the entire Purgatorio, which indicates that Dante the poet considered Pride his besetting sin (and he had much to be proud about).

Now Virgil instructs Dante to look down and see the carved images of renown figures from classical and Biblical history, personages destroyed by their own pride. There’s a remarkable point that begins in line 36 where the voice of the poet goes from describing what he sees on the carvings (“My eyes beheld Thymbraeus, Pallas, and Mars…”) to addressing them directly (“Ah, Saul, you too appeared there, dead…”), as if the uncanny realism of God’s carvings, which he’d remarked on before, seized his imagination so fiercely that he started talking back to the movie screen, as it were.

Dead seemed the dead, living seemed the living.

He who beheld the real events on which I walked,

head bent, saw them no better than did I.

Here, again, is the power of great art to create emotional verisimilitude, overcoming our senses, and provoking metanoia — that is, a sudden realization of the moral and spiritual reality of one’s condition, leading to a change of heart. Of course, art that brings to life lies can mislead one just as profoundly, as we will discuss later.

Then Dante addresses us readers sarcastically:

Wax proud then, go your way with head held high,

you sons of Eve, and no, do not bend down your face

and so reflect upon your evil path!

These are the words of a man whose heart has been seized and is on fire with repentance brought about by humility. After this episode, Virgil tells him to snap out of it: “Raise your head!” he orders. “This is not the time for walking so absorbed.”

Why not? Because an Angel of the Lord approaches to absolve Dante of the sin of Pride, and to remove a P from his forehead. “Show reverence in your face and bearing,” says Virgil, “so that he may be pleased to send us upward. Consider that this day will never dawn again.”

What a powerful statement. Virgil is teaching Dante how repentance, confession, and absolution work. The time for mourning one’s sins is limited. When sacramental absolution comes, one should raise one’s head to receive that mercy with reverence — and not look back on the sins that have been forgiven.

Confession was a tremendous blessing to me when I became a Catholic back in 1993. Most people coming into the Church (same with the Orthodox Church, which has confession and takes it very seriously) dread it, but for me, it was one of the best things about becoming Catholic. Why? Because it gave me the assurance that I had been forgiven. In my early teenage years, when I was still a Protestant, and went through a couple of years of intense religiosity, I was deeply conscious of my sins. Though I believed that God forgave me when I asked Him for forgiveness, I could never really be sure that I had asked in the right way. I kept mulling over my sins, wondering if I had truly been forgiven, because I could not let go of them. This was a problem with me, not with God, understand. But it was a problem.

The amazing thing I discovered as a new Catholic was that when the priest pronounced the words of absolution in persona Christi, I was free. I knew I was sorry when I confessed, but there was something about the ritual that severed my psychological bonds to sins that had been forgiven. Of course I might end up in the confessional a week later, confessing the same sins, but that’s okay. That’s what it means to climb the long, hard mountain to sanctity. The point was, when I walked out of that confessional, I was free. What’s past is past. Consider that this day will never dawn again.

I have always cherished confession, and always will. It is one of the greatest mercies of life in Orthodoxy and Catholicism.

The Angel who acts in persona Christi in this canto is described thus:

The fair creature, garbed in white,

came toward us. In his face there was what seemed

the shimmering of the morning star.

The morning star, of course, is a term used to describe Lucifer before he fell from heaven out of Pride. The very first carving that Dante walks on depicts Lucifer’s fall. Dante glimpses in the Angel’s face a spark of what Lucifer was, before his Pride destroyed him. The Angel welcomes Dante, promises him that the climb from this point on will be easy, and taps him on the forehead with his wings. This removes one of the Ps on Dante’s forehead, and makes the others lighter — a sign that Pride is the base on which all the other sins are built.

Off Dante and Virgil go, climbing to the next terrace, listening to a faraway choir singing one of the Beatitudes, Blessed are the poor in spirit. Master, asks Dante, what’s happening? Virgil tells him that when all the Ps are erased,

“your legs shall be so mastered by good will,

not only will they feel no effort going up,

but they will take delight in being urged to.”

The more one practices virtue, the easier it becomes to do. This is the lesson.

I’m finishing this in Dallas. My flight for Grand Rapids is boarding. Boudin is still intact. Later, folks.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.