Modern ‘Love’ in the Age of Tinder

Listen to that interview from public radio’s “The Takeaway.” It’s with a Columbia University sophomore named Jordana Narin, who is the winner of this year’s New York Times Modern Love College Essay Contest. Her winning entry is about the challenges of finding real love in a world in which the nature of relationships is determined by technology — which leaves them crushingly indeterminate. From the essay, in which she talks about losing her virginity to a guy she only really knew from their online relationship, and who refused to commit in any way to her. In the way of their generation, he kept things open:

On the Saturday-night train back to Manhattan, I cried. Back in my dorm room, buried under the covers so my roommates wouldn’t hear, I fell asleep with a wet pillow and puffy eyes.

The next morning I awoke to a string of texts from him: “You get back OK?” “Let’s do it again soon :)”

And we did, meeting up for drinks in the city, spending the night at my place, neither of us daring to raise the subject of what we were doing or what we meant to each other. I kept telling myself I’d be fine.

And I was. I am.

But now, more than three years after our first kiss and more than a year after our first time, I’m still not over the possibility of him, the possibility of us. And he has no idea.

I’m told my generation will be remembered for our callous commitments and rudimentary romances. We hook up. We sext. We swipe right.

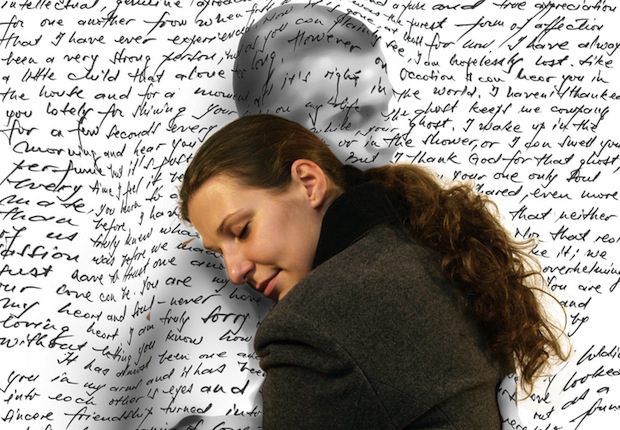

All the while, we avoid labels and try to bury our emotions. We aren’t supposed to want anything serious; not now, anyway. But a void is created when we refrain from telling it like it is, from allowing ourselves to feel how we feel. And in that unoccupied space, we’re dangerously free to create our own realities.

I wouldn’t have understood the full scope of what this young woman is saying in her essay without the interview, which is short. In the segment, Narin says that men and women in her generation don’t have actual romantic relationships anymore. It’s all casual, non-committal sex. “Nobody knows whether their own feelings are real,” she says.

Our generation doesn’t have relationships anymore. Nobody to call their own. Just casual. Nobody knows whether their own feelings are real.

She tells the interviewer that there’s lots of making out and sex, but nobody wants to be emotionally vulnerable to anybody else. The interviewer says that none of this is new, that men and women forever have had a hard time being emotionally confident as they’re trying to work their way through romance. Now, however, it’s possible to “live in your fear,” he says. What has changed?

“Technology,” she said. She explained that you can avoid direct, sustained talking to real people by using technology.

“Everyone in college uses Tinder,” she said, referring to the wildly popular dating and hook-up app. “You can literally swipe right and find someone just to hang out for the night. There’s no commitments required, and I think that makes committing to someone even harder, because it’s so normal, and so expected even, to not want to commit.”

“In a different time, my grandparents, my great grandparents, they might have thought they were missing out on casual sex,” she says. “But since my generation has been saddled down with that, we kind of look to the past and say well, wasn’t that nice. I think both are optimal. I’m a huge feminist, and I think women should be able to do whatever they want to do. If a woman wants to have tons of casual sex, she totally should. But I think that there should be the option. And they shouldn’t be gendered, women and men. But there should be the option of being in a relationship.”

If you listen to the interview, her vocal intonations give the impression that after she thought nice things about old-fashioned romance, she had to catch herself and assert that she believes casual sex and lots of it is fantastic, and nobody should say it’s wrong. But it would be nice if young people could have the option of old-fashioned romance.

It’s so sweet and naive, but ultimately telling, and tragic, that Jordana Narin doesn’t understand that you cannot have complete sexual freedom as she envisions it, but also have a culture conducive to meaningful courtship. She wants the freedom that Tinder and the culture it creates gives her, but it also leaves her cold and lonely for something real.

The interviewer senses her unhappiness, and tells her it sounds like she wants something more, but doesn’t know how to ask for it.

“That’s a spot on analysis. My friends and I, we want something more. We don’t know how to ask for it. But I think it’s a learning process,” she responds.

“It’s just hard, I think, because my generation, we know what to do with our brains. We live in a super-connected world. … We can do all that, but it’s the very basics that we’ve forgotten.”

I suppose it’s because I’m so elderly and out of it that I had no idea things had gotten to this point. This “freedom” is slavery to the passions and to complete social atomization. This “modern love” makes real love next to impossible. Who could possibly be happy with this? And yet, to listen to this student, it seems impossible for them to imagine another way of living.

This is what I mean when I talk about anarchy. It’s easy for educated middle-class people to see the cultural anarchy on the streets of West Baltimore and grasp the destructive consequences of extreme disorder in the hearts of those impoverished people. But what is at the core of the Tinder generation’s malaise other than anarchy? They order their intimate lives according to their individual desires, which requires them to keep commitment at bay, because to submit to something — or rather, someone — other than the desiring Self would require limiting individual desire, and choice. It’s pathetic, actually, that Jordana Narin celebrates having a wide range of choice in sexual behavior, but laments that the Greek diner menu of sexual possibility excludes the realistic possibility of true love. Is there no one to say, “Friend, this is not an aberration, but is rather in the nature of the thing you’ve accepted.”

As long as you participate wholly in Tinder World, you will be as trapped in your own kind of inhuman self-destruction as the people in the inner city are trapped in their own cultural dysfunction. The idea that there is no other way to live is why any destructive set of ideas and practices has such power over the people caught up in it.

When I get started on this Benedict Option book, a significant part of it will have to be a consideration of how the technological order (in terms of social media and communications technology) orders our emotional lives and social connections, and distorts them. I suspect a strategic retreat from social media and a world in which most human connections are virtual is going to be a key part of the Benedict Option, which seeks to restore the human, to rescue the really real.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.