We, the Essential Freaks

Daniel McInerny has a fine short essay in praise of Flannery O’Connor’s advice to writers, via her collected letters, which is one of the most treasured books on my shelf. McInerny writes:

A character’s response to that offering is O’Connor’s overriding concern as an author. “I don’t think you should write something as long as a novel around anything that is not of the gravest concern to you and everybody else and for me this is always the conflict between an attraction for the Holy and the disbelief in it that we breathe in with the air of the times” (Letter to John Hawkes, 13 September, 1959).

In order to make that “attraction for the Holy” plausible in our increasingly nihilistic age, O’Connor uses elements of the grotesque and of violence to help us see the strangeness and awesome power of the Incarnation. “Charity is hard and endures,” she writes in a letter to Cecil Dawkins (9 December, 1958). Sentimentalism is the bane of her imagination: “I believe that there are many rough beasts now slouching toward Bethlehem to be born and that I have reported the progress of a few of them, and when I see [my] stories described as horror stories I am always amused because the reviewer has hold of the wrong horror” (Letter to A., 20 July, 1955).

The wrong horror. I smiled when I read that, not only because I am an ardent fan of O’Connor’s short stories, but because I realized that this emphasis on the grotesque as a way to reawaken a benumbed reader to moral and spiritual reality is exactly the strategy that Dante uses in his Inferno.

In the poem, the pilgrim Dante (that is, the poem’s protagonist) finds himself lost in a dark wood — a symbol of his spiritual condition. He has become insensitive to the reality of sin and what it has done to both his own life and to the life of his community in Italy, lost to chaos, corruption, strife, and war. To restore him, Virgil first must lead Dante through Hell, and show him many grotesque things to shock his sensibilities, and to scare him straight.

Whenever I hear people complain that the Inferno is nothing but sadism and ghoulishness, I know that they have hold of the wrong kind of horror. The vivid grotesqueries of the Inferno exist to shock the reader into considering what sin does to a soul. The Slanderers, for example, spend eternity living in a cesspit, their mouths full of excrement. In this unforgettable image, the poet shows us what it means to slander people. Over and over the poet does this, as a way to slap your moral imagination hard across the cheek.

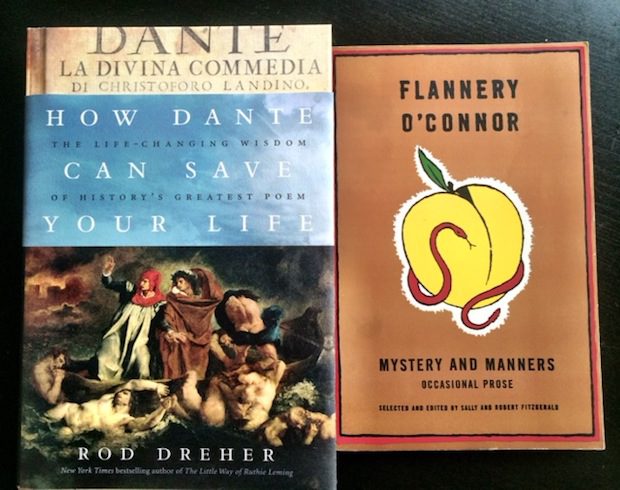

Sometimes, it works. In my book How Dante Can Change Your Life — in bookstores today! — I write about how the first breakthrough in my own spiritual and physical healing came in a particular circle of Hell, when I saw what the sinners there were enduring, and was struck by the recognition of myself in that scene. Yes, I thought, this is exactly how it is with me. You will find yourself on a different level, perhaps, but you will find yourself. Dante does not want to sugarcoat the underlying reality of what we do to ourselves when we put our own egos and passions above the Good.

Flannery O’Connor is a world away from Dante, but in this famous passage from her book of essays Mystery and Manners, the Southern novelist puts her finger on what Dante is up to:

I think it is safe to say that while the South is hardly Christ-centered, it is most certainly Christ-haunted. The Southerner, who isn’t convinced of it, is very much afraid that he may have been formed in the image and likeness of God. Ghosts can be very fierce and instructive. They cast strange shadows, particularly in our literature. In any case, it is when the freak can be sensed as a figure for our essential displacement that he attains some depth in literature.

The damned in Dante’s Inferno are all freaks of the most vivid, visceral sort. But they are also recognizably human. The poet is using their freakishness as a mirror. This, he says, is who we all are deep down, if we remain bound to our egos, and follow the logic of our own egotism out to its logical end in eternity. He frames it in Catholic imagery because that’s what he had to work with. But as O’Connor wisely points out:

There is no reason why fixed dogma should fix anything that the writer sees in the world. On the contrary, dogma is an instrument for penetrating reality. Christian dogma is about the only thing left in the world that surely guards and respects mystery.

She wasn’t writing about Dante there, but he certainly uses Catholic dogma to penetrate the deep mysteries of the human heart. I tell people that you don’t have to believe in a literal Purgatory to profit from reading Purgatorio, because it is a symbol of the arduous struggle every person who chooses not to be a slave to his passions undertakes to master them. A Christian will read Purgatorio (and the other two books) with a deeper sense of appreciation for Dante’s message, but an unbeliever will see the people he knows, and the person he is, in the souls of the Inferno‘s damned and the penitents of Purgatorio. Dante made his characters and their settings exaggerated and grotesque because the people of his world — wealthy, chaotic, fractured, vice-ridden, sensual, passionate Tuscany of the High Middle Ages — needed to be shocked back into reality. This is what the pilgrim Dante’s journey through the Inferno is: Virgil’s strong medicine to sober up a man who has become insensate to the true state of his soul.

It worked on me too, and I did not see it coming.

In a 1989 essay on O’Connor, Bruce Bawer wrote:

As for the supposed grotesqueness of her vision, she argues that “writers who see by the light of their Christian faith will have, in these times, the sharpest eyes for the grotesque, for the perverse, and for the unacceptable.” For “[t]he novelist with Christian concerns will find in modern life distortions which are repugnant to him, and his problem will be to make these appear as distortions to an audience which is used to seeing them as natural; and he may well be forced to take ever more violent means to get his vision across to this hostile audience.” Her fiction is violent, in other words, because when your audience does not hold the same beliefs that you do, “then you have to make your vision apparent by shock—to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost blind you draw large and startling figures.”

This, too, is what Dante is about. He shouts, he frightens, he prophesies, he dazzles. If you are the kind of reader who thinks that Dante’s Inferno is surely a horror story, you should consider that maybe you have hold of the wrong kind of horror. A California reader wrote to O’Connor to tell her that at the end of a long day, she wants to read something uplifting, not depressing like she thought O’Connor’s stories were. Flannery said in response to that that if this California reader’s heart was in the right place, it would have been lifted up.

So too with Dante’s work. The ghosts of Francesca, Farinata, Pier della Vigne, and the other unforgettable character in Dante’s Inferno are figures of our essential displacement. If you do not see something of yourself in them, my fellow freak, you are not looking hard enough.

Say, I see that the Amazon page for How Dante Can Save Your Life has its first review, from the Englewood Review of Books. Five stars! Look:

How Dante Can Save Your Life is a book about finding ourselves, and understanding the world we live in, which actually hasn’t changed all that much since Dante wrote his epic in the fourteenth century. The bulk of the book is spent on Dante’s Inferno, which offers an explanation of “Why you are broken,” an insightful look at the fallen world in which we must navigate our lives. A rich mix of memoir and social commentary, Dreher’s book is a wonderful illustration of how people of faith can have their imaginations transformed by the practice of slow and careful reading of good, well-crafted books.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.