Inferno, Cantos 5-7

One imagines that Dante leaves Limbo feeling pretty good about things. He has spent time with some of the greatest poets and philosophers who ever lived, and done so in a resort setting. But he is about to receive a harsh awakening.

In Canto 5, the pilgrim and Virgil descend to the eighth circle of Hell, where the Lustful dwell. Here is one of the most terrifying and memorable images of the entire poem:

There stands Minos, snarling, terrible.

He examines each offender at the entrance,

judges and dispatches as he encoils himself.

I mean that when the ill-begotten soul

stands there before him it confesses all,

and that accomplished judge of sins

decides what place in Hell is fit for it,

then coils his tail around himself to count

how many circles down the soul must go.

Virgil instructs Minos to leave Dante alone, because he is protected by God (though no one in Hell mentions the name of God directly). The demon warns the pilgrim, “beware how you come in and whom you trust” — signaling that not everyone with whom he speaks in Hell is a reliable narrator of their own history. And so the two pass into the eighth circle, which is a dark place in which the souls of the damned are blown about eternally in a “hellish squall, which never rests.” As Ron Herzman says, in Dante’s Inferno, the damned get what they wanted in life; the Lustful wanted to give themselves over to turbulent, uncontrollable passion — and that’s what they get.

I understood that to such torment

the carnal sinners are condemned,

they who make reason subject to desire.

See how the poet works here? The punishment for the Lustful mimics the way Lust works on the soul, tossing and turning it and confusing the reason. Virgil shows Dante in the passing tempest the souls of Semiramis, of Helen of Troy, Achilles, Paris, and Tristan — great lovers all, who had been overcome by lust. Dante asks Virgil for permission to speak to someone. Virgil says, “If you entreat them by the love that leads them, they will come.”

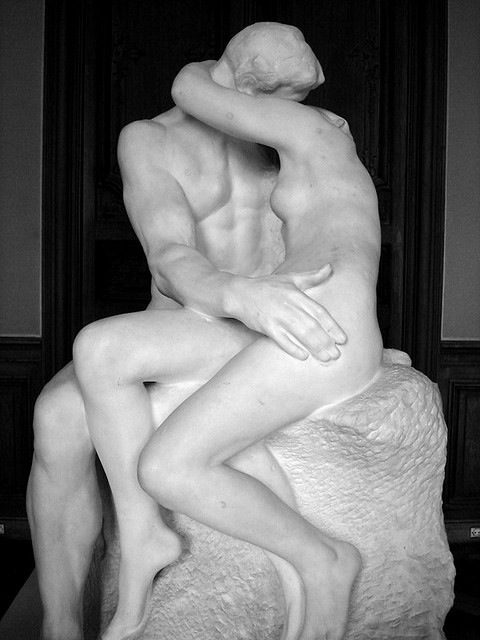

And so he does. A pair of lovers who are bound to each other forever stop to visit with the pilgrim and his master. This is Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta, real-life lovers of Dante’s day. They had been caught in an adulterous clutch by Francesca’s husband Giovanni, who happened to be Paolo’s brother, who was also married. He murdered them both. They lived for lust, and now they live an eternal death, inseparable. Rodin’s famous sculpture The Kiss depicts Francesca and Paolo:

I had always thought of that image as one of all-consuming passion, and, of course, it is. But it was a romantic image, a positive one. When I learned that it actually depicted these two damned lovers, it changed the way I saw it — but did so in a morally instructive way. In our time, we can’t help seeing these lovers as nothing but objects of beauty. That is how Francesca and Paolo saw themselves. They were so focused on each other, and satisfying their desire for each other, that they saw nothing else.

The Francesca episode is perhaps the most famous in the entire Commedia, and a terrific one for coming to understand how Dante thinks. It is helpful to consider this passage from Matthew 22, in which Jesus is questioned:

“Master, which is the greatest commandment of the Law?”

Jesus said to him, “You must love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your mind. This is the greatest and first commandment. The second resembles it: You must love your neighbor as yourself. On these commandments hang the whole law, and the prophets too.”

All of us must put God first in all things. That is the prime directive. Once we have done that, we must love our neighbor as we love ourself — and that means seeking the good of our neighbor. What is the good of our neighbor? We can know this only by knowing what God expects of us, and wants of us. If our neighbor confesses to us that she is in love with another woman’s husband, we may be certain that that violates God’s law. If we ourselves would want to obey God because it is the right thing to do, then if we love our neighbor as ourself, we must want her to do the right thing also. It is not loving to encourage her in her adultery. That does not mean we have to cut her off, necessarily, but Jesus here does instruct us on what we should desire, both for ourselves and our neighbor.

The first two books of the Commedia are about the purification of desire. If sin comes from disordered desire — that is, loving the wrong things, or loving the right things in the wrong way — then to be delivered from the power of sin requires re-ordering our desire. That means renouncing the control our desires have over us. When Virgil tells Dante at the outset that the souls of the damned have lost the good of intellect, he means that they have no control over their passions; because they gave themselves over to their passions in life, they have become their passions for eternity in death. Intellection is what separates us from the animals. The damned are no better than animals.

What we love is what we will seek to achieve or to gain. It has never been easy for any man to resist the passions — that is, disordered desires — but it is especially difficult today, in a sensual, consumer society that teaches us that fulfilling our desires is how we come to know and to live out our deepest selves. This is a lie, but it’s a lie that Dante must have accepted in his time, because he himself was on the road to Hell. He had to go down into Hell before he could be restored because he had to be reawakened to what sin means, and to what allowing ourselves to be possessed by the passions will do to us.

It’s important to understand that desire itself is not evil. As Virgil explains much later to the pilgrim, in Purgatory:

So, you can understand how love must be

the seed of every virtue growing in you,

and every deed that merits punishment.

To love God above all things, and to love your neighbor as yourself, is to desire. But those desires are purified, because they are in harmony with the Creator’s will. In this life, we are not to seek the extermination of the passions; remember that Hell’s vestibule is populated with the passionless. Rather, we are to seek to transform our passions, redirecting them away from serving the ego, and toward serving God and other people. We are to make our passions subject to our reason. God gave us free will, and He expects us to use it.

To be mired in sin is like being physically ill. Few people become deathly ill instantly, and fewer are healed instantly. To be delivered from control of the passions requires penitence. This is what Purgatorio is about: correcting what is broken within us. Paradiso symbolizes life full of grace, when all of our disordered passions are replaced by passionately desiring the Good.

Before we can begin the healing process, we have to understand the nature of the illness. This is why the Francesca episode is so instructive. As Dante begins to question her about how she and her lover ended up in Hell, she answers with highblown flattery:

“O living creature, gracious and kind,

that come through somber air to visit us

who stained the world with blood,

“if the King of the universe were our friend

we would pray that He might give you peace,

since you show pity for our grievous plight.”

She’s playing him. Francesca tells him that he is more compassionate than God, who has turned His back on him. That should have been a signal to Dante right then that she is unreliable. Francesca goes on:

“Love, quick to kindle in the gentle heart,

seized this man with the fair form taken from me.

The way of it afflicts me still.

“Love, which absolves no one beloved from loving,

seized me so strongly with his charm that,

as you see, it has not left me yet.

“Love brought us to one death. …”

What she is doing here is proclaiming the worldview of the medieval cult of courtly love, which made an idol, a kind of religion, of erotic passion. The first line — “Love, quick to kindle in a gentle heart” — is a direct quote from a sonnet in Dante’s first great work, Vita nuova. The second quote is from a contemporary manual, The Art of Courtly Love (though Esolen points out that the manual also says that sexual passion must be kept within marriage) Francesca presents erotic desire as an irresistible passion. How can you blame us? she says. We couldn’t resist.

And then she tells the pilgrim about the deed that led to their affair. They were reading about Lancelot’s adulterous affair with Queen Guinevere, and “how love enthralled him.” Francesca describes how she and Paolo became enflamed by desire for each other as they read together. Then:

“When we read how the longed-for smile

was kissed by so renowned a lover, this man,

who never shall be parted from me,

“all trembling, kissed me on my mouth.

A Galeotto was the book and he that wrote it.

That day we read in it no further.”

Meaning that they put the book down and went to bed together. “Galeotto” is the Italian form of Galehaut, a figure from the Arthurian legends, and was a go-between linking Lancelot to Guinevere. Francesca blames the book and its author for her and Paolo’s damnation. You will notice that Francesca blames everybody for her state except herself.

When Dante hears all this, he faints. It could be that he swoons out of pity for these two. After all, Dante as a younger poet had been part of the courtly love movement, and wrote verse extolling its principles. To see the tragic of the doomed lovers may have overcome him for the same reason romantic-minded people today would pity them. The pilgrim will learn, though, that pity for the damned is wrong, for reasons we will get into when Virgil rebukes him for it later on the journey.

Cook & Herzman, however, suggest another reason for Dante’s pity on Francesca and Paolo, or at least an additional reason, one that I find persuasive. Francesca has spoken of how reading the literature of romantic love had formed her mind and her heart, and taught her that to follow her romantic passion was not only right, but impossible to deny. Young Dante wrote some of the poetry that misled her. Recall that in Limbo, he had been feeling pretty good about himself as a poet, treated as a peer by Homer, Virgil, and the others. And now, one canto later, he sees the damage a poet can do if his words are not informed by truth. The Commedia is a poem about connections. It may be the case that Dante grasps the connection he has to the damnation of these two lovers, and he can’t bear the thought. In Canto 11 of Purgatorio, the penitent pilgrim will learn of the necessity for art to be grounded in moral truth. However unfair and self-serving it is for Francesca to blame the books for her fate, it’s important to keep in mind that art really does instruct us in how to think, to feel, and to behave. To be an artist is to have great power.

One more word about Francesca before we leave her and Paolo to the wind. I have at times quoted on this blog from J.R.R. Tolkien’s letter to his son Michael, in which he advised the young man to be wary of the lie of courtly love, which exalts women as love objects, as goddesses:

It is not wholly true, and it is not perfectly ‘theocentric’. It takes, or at any rate has in the past taken, the young man’s eye off women as they are, as companions in shipwreck not guiding stars. (One result is for observation of the actual to make the young man turn cynical.) To forget their desires, needs and temptations. It inculcates exaggerated notions of ‘true love’, as a fire from without, a permanent exaltation, unrelated to age, childbearing, and plain life, and unrelated to will and purpose. (One result of that is to make young folk look for a ‘love’ that will keep them always nice and warm in a cold world, without any effort of theirs; and the incurably romantic go on looking even in the squalor of the divorce courts).

I was so startled to read this for the first time that I can recall exactly where I was (on the left side of the couch, facing the fireplace, in my Capitol Hill apartment, midmorning on a cold mid-February day). This was exactly my own condition: seeing “true love” as a permanent exaltation, and losing my way badly because of it, mostly because I had a habit of falling madly in love with women I couldn’t have. We do not suffer from the medieval cult of courtly love, but we do have our own version of romantic love as the absolute telos of life, and of erotic desire as self-justifying. And like Francesca, we are very good at concealing our own motivations from ourselves, and in teaching ourselves how to be helpless. As Prue Shaw says of Francesca’s speech:

For all its charm and eloquence, it is a self-serving exercise. It is an exercise in justifying our actions and exonerating herself, in denying her personal responsibility. Love is to blame. The book is to blame. Anything is to blame except Francesca herself. And her self-justification echoes literary texts of Dante’s own fashioning.

It’s society’s fault. It’s my parents’ fault. It’s the church’s fault. It’s the fault of racists, of sexists, of homophobes, of anti-Christian bigots, of anti-Semites. It’s the fault of the rich, the fault of the poor. And so forth. Anybody’s fault except my own. One of the key lessons I learned from Dante, one that saved my life, was the realization that no matter what fault others may have in bringing me to grief, I retain control over my own reaction to their actions. I did not cause the judgment that kept me from coming home as I had hoped to, and I could not control what others believed. But I could control my own reaction to it.

This was liberating. To accept that freedom, though, I had to move past blame, even if that blame was in some real sense merited. If I remained in that place of internal misery, I would have no one to blame but myself.

A final word: Herzman and Cook point out that Francesca’s relationship to Lust is a template explaining how all those to come who are guilty of sins of incontinence (Gluttony, Greed, Wastefulness, Anger) relate to their sin. They are overcome by desire of the flesh.

Moving on to Canto 6, Dante finds himself in the third circle, a place of “hateful rain, cold and leaden, changeless in its monotony.” God rained down manna on the hungry Israelites in the desert, but those who dwell in this barren wasteland get nothing but cold rain. The ground is mucky and foul-smelling. Lying in the sludge are the Gluttons, watched over by the demon dog Cerberus, who tortures them with his claws. Virgil distracts him by throwing mud in his mouth. The dog is himself such a glutton that he busies himself digesting the earth, giving Dante and Virgil the liberty to pass through. Esolen points out that in the Aeneid, Cerberus is quieted by a honey cake tossed into his mouth. In Dante’s Hell, though, even something as sweet-tasting as a honey cake is turned into stinking mud. This is what the the disordered delights of the gourmand turn to in Hell: spending eternity face down in horrible-smelling mud. From a spiritual perspective, to gorge on food and drink is the same thing as gorging on mud, on foulness, on filth.

From the muck emerges a man, Ciacco (Italian for “pig”). In this canto, Dante doesn’t dwell on the sin of Gluttony, but rather makes Ciacco a voice commenting on the politics of Florence. The general point to take here is that private sin has public consequences. Ciacco prophesies that civil war will come to Florence because of the envy inflaming the passions of the city’s great men. In fact, this happened in 1302, resulting in Dante’s exile. (Remember that Dante sets the poem in 1300, but began writing it in 1307.)

Canto 7 takes the two men into the circle of the Hoarders and Wasters — that is, those whose controlling sin was a disordered relationship to money and material objects. They were either greedy, or profligate. The Hoarders and Wasters both “shove burdens forward with their chests” from opposite sides, crashing into each other interminably, shouting at each other as they do. The Hoarders do not understand the Wasters, and curse them; the Wasters do likewise to the Hoarders. They despise each other over things. Among their number are a number of priests, monks, cardinals, and popes. Says Virgil:

“Now you see, my son, what brief mockery

Fortune makes of goods we trust her with,

for which the race of men embroil themselves.

“All the gold that lies beneath the moon,

or ever did, could never give a moment’s rest

to any of these wearied souls.”

Virgil delivers a short oration on Fortune, saying that it waxes and wanes, and that people have no business blaming bad luck for their situations. Things happen. The world passes away. We lose ourselves by caring too much for the transient things, ignoring the permanent things, the things of heaven. This is how the Hoarders and the Wasters have come to eternal grief. Esolen reads this as saying what to unbelievers is blind luck is read by the virtuous as the outworking of divine providence. That is to say, all things, even terrible misfortune (such as Dante experienced in his exile) can work to our salvation, if we let it.

On they walk, downward toward the pit, approaching the banks of the River Styx. They first slog through a swamp:

And I, my gaze transfixed, could see

people with angry faces in that bog,

naked, their bodies smeared with mud.

They struck each other with their hands,

their heads, their chests and feet

and tore each other with their teeth.

There lie the souls of the Wrathful, who were incontinent in their anger. They make communion between themselves and others impossible. Their anger provokes nothing but division and fighting. Beneath the surface, beyond Dante’s vision, lie the Sullen — those who marinated themselves in anger. They make communion between themselves and others impossible for another reason: their form of anger drives others away by its bitterness. You can tell they are there, says Virgil, because you can see their bubbles make the water seethe. Virgil:

“Fixed in the slime they say: ‘We were sullen

in the sweet air that in the sun rejoices,

filled as we were with slothful fumes.

“‘Now we are sullen in black mire.'”

What a powerful image. These bitter souls wasted the joy of life in resentment. Their anger did not express itself in rage at others, but imprisoned themselves. If the Wrathful are too free-spending of their anger, the Sullen are hoarders of anger. And now, as ever, they get what they wanted.

Haven’t you known people like that? I have several people like this in mind from my past. One of them in particular comes to mind; I will call him Arthur. I assure you that my made-up figure is composed of real people I have known. Poor Arthur had a number of misfortunes earlier in his life. He filled himself with self-pity, and demanded that everyone around him share his pity. You learned not to ask Arthur, “How are you?”, because he took that as an invitation to talk about all the crappy things that had happened to him since last you saw him. The man was incapable of experiencing joy, or gratitude, or any good thing. If you gave him a piece of chocolate cake, he would complain that he preferred pound cake. Or if you gave him pound cake, he would complain that you really shouldn’t be doing that, because he ought to be losing weight. Arthur was a black hole of suck, in love with his bitterness. Last I heard, Arthur had moved from job to job, and was blaming employers for not appreciating his gifts. The man had absolutely no idea how off-putting his sullenness was, and ultimately, how egocentric.

Virgil and Dante make their way across the marshy Styx, and come to the foot of a tower. We will pick up their journey tomorrow.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.