Chait, Meet Law of Merited Impossibility

J. Bryan Lowder, an LGBT beat writer for Slate, thinks Jon Chait has a point about ideological policing on the Left, but that he also had it coming. Or something. Excerpts:

[Chait’s] conclusion: “Politics in a democracy is still based on getting people to agree with you, not making them afraid to disagree.”

Eminently reasonable statement, right? But when you start picking apart the writing that comes before it—writing that’s dense with rhetorical choreography, questionable conflations, and tenuous juxtapositions—Chait’s measured facade starts to crack, and what’s behind it is actually kind of fascinating. Many progressive critics have written off the piece as the whining of an out-of-touch white guy, and that’s certainly a fair response. But it’s also undeniable that Chait has described a real thing in our cultural moment (the more honest responders have admitted that much) and, at least to my mind, some of what he observes about it is correct. Rather than snarking or condemning Chait out-of-hand, I think we ought to take a closer look at the underlying logic of his complaint—the good and the bad—to see what we can learn, not only about the purported dangers of P.C. culture, but also about the perhaps equally troubling assumptions of those who fear it.

OK, imagine how it would sound if someone dismissed an opinion of someone else as the rantings of “an out-of-touch black woman” as “certainly a fair response.” Lowder shows how much he’s bought into the identity politics of the cultural left. He continues:

Chait may be somewhat melodramatic, but he is not totally off the mark. There are definitely some troubling aspects to the leftist mode of identity-based critique [like the flippant one you just made! — RD] of which we should be wary. But his refusal in this essay either to grapple with deeply ingrained power differentials between social groups (hardly a radical proposition at this point) or to question the assumed virtue of his own rather jejune, “Let Us Gather at the Table of Reason” vision of liberal social discourse is in many ways more worrisome.

So Chait, in calling for a return to liberal standards, is the real enemy here. You see where this is going.

More:

Here, Chait (and Sulllivan and Dan Savage, who all echoed him on this point) picks up on what is truly the most self-defeating part of contemporary PC culture—the refusal to distinguish between ignorance and genuine disagreement. We are not talking, to be clear, about disagreeing over, say, the value of trans lives or the fairness of gay marriage; those are no longer things seriously up for debate. [Emphasis mine — RD] But plenty of legitimate contentions remain.

Lowder has just written off nearly half the country as having opinions on a subject as fundamental as marriage and family as not worth taking seriously. Again, he’s an example of what he supposedly decries. It turns out that J. Bryan himself was once set upon by the leftie mob for a column he wrote questioning the demand that publications should start using made-up replacements for “him” and “her.” He responds:

Here’s the problem with all this: I am actually not ignorant or unenlightened as to why a genderqueer person might think a special pronoun is desirable. (And indeed, I support that person’s right to ask their family and friends to use their preferred pronoun.) I have read and listened to explanations for this small point of social justice etiquette many times, considered it at length—and still I maintain that it is not an appropriate thing to demand of strangers and publications. On this point, I and those critics will have to disagree, and considered disagreement delivered in good faith does not make me a conservative bigot, nor does it necessitate an apology or “further reading” or silence on my part.”

Ah, I get it. J. Bryan says he’s not a bigot, and ought to be free to disagree in good faith. Hello! What do you think so many of us to the right of you have been saying, J. Bryan! You appear to have decided that people who are more conservative (or libertarian) than you on questions related to homosexuality can be at times fairly criticized on the basis of their race or other form of identity, and that people who fundamentally disagree with you on the matter should be effectively silenced — but you want to carve out a special niche for yourself? As the reader who sent me this item comments, “Oh boy, J. Bryan. Look out, fella. This ain’t going to be pretty for you unless you fall in line.”

Here’s J. Bryan’s kicker:

I can assure Chait that occasionally hearing the complaints and critiques of the oppressed people we earn a living writing about is far less exhausting than actually having to live under that oppression—a negative tweet here and there is hardly unreasonable.

“A negative tweet here and there”? J. Bryan is deluded. In his piece, Chait quotes liberal people in academia who tell him that people are afraid to say what they think for fear of offending one of these militant snowflakes, and bringing a ton of bricks down on their heads. This is a real thing. I work in media and publishing, and I’m telling you, the left-wing groupthink within the industry is massive — and significant. Which is what brings me to the most infuriating aspect of this Slate piece:

First, we need to restore a sense of scale to this discussion. Chait’s complaint—like other, similar ones—often asks us to imagine that millions of well-meaning American citizens are daily receiving cease-and-desist orders from so-called “Social Justice Warriors.” This is not true. Most Americans do not live and work and express their trenchant takes on the social issues of the day on Twitter or in the other areas of the Internet where these kinds of skirmishes occur. Most Americans have never heard of SJWs or microaggressions. Most Americans do not live with the anxiety, as we progressive opinion writers sometimes do, that we will be denounced as somehow retrograde or phobic or bigoted for accidentally offending a handful of vocal digital activists. Most Americans would probably find such anxieties quite ridiculous, the state of the world considered.

Politically correct zealotry may be a threat to certain individuals’ continuing stream of social media goodwill, but it is not a threat to Our Democracy. Not really.

Here’s why that’s a dodge. At the media blog GetReligion the other day, Bobby Ross highlighted a Washington Post story about two Oklahoma lesbians who want to get married in a state that forbids it, and within a conservative culture that broadly disagrees with same-sex marriage. Ross writes:

On the one hand, the Post does a pretty nice job of highlighting the emotional experience of the couple featured. On the other hand, the newspaper avoids any meaningful exploration of religion, an obviously key factor at play in this state — and in this story — but one that the Post relegates to a cameo role.

As Ross points out, there is nothing remotely like a well-considered discussion of religion and the role it plays in shaping the culture of Oklahoma. It’s just a prop within the story the reporter wants to tell. There have been thousands and thousands of stories like this over the past decade or so, in which broadcast and print journalists have either ignored or glossed over the deeper objections religious people have to same-sex marriage. I have seen this myself: the deep and sincere conviction among people in media and publishing that there simply is not other side in the gay marriage issue, and that feeling an obligation to explain why someone would oppose gay marriage would be on part with feeling an obligation to explain why a Klansman hates black people. You think I’m exaggerating? I have heard exactly this comparison, and more than once.

Believe it or not, I think it is a good thing that the media have paid more attention to the lives of actual gay people, and have told their stories. This has had a lot to do with why gay rights has gone so far, so fast. But the media have had not remotely the same sense of responsibility in telling the stories of traditionally religious people on this issue, to show that, in J. Bryan Lowder’s words, “considered disagreement delivered in good faith does not make me a conservative bigot, nor does it necessitate an apology or ‘further reading’ or silence on my part.”

I had the head of a major media company tell me in conversation once that there is no other side to the gay rights story, and anybody who thinks there is one is a bigot. This is a man whose opinions decide what counts as news, and what counts as acceptable opinion. This kind of thing happens all over on this issue. And it moves a culture. When J. Bryan Lowder thinks the problem is just SJW nuts sending out the occasional nasty tweet, he is either being exceptionally foolish or is so deep inside the bubble that he has no idea how ignorant he is of how things actually work in the world.

I know people personally — people who are political and/or religious conservatives — who work in corporate America who are terrified of losing their jobs because of this stuff. They all go to mandatory diversity training programs, and they keep their mouths shut, and never utter a peep that deviates from the party line, because they know it can and will be used against them. A friend of mine who works for a major financial institution, in an office with several gay colleagues (whom he likes and respects very much) wonders how long it will be before his refusal to identify himself as an LGBT “ally” costs him his job. Understand, he’s not even taking a stand against LGBTs in the workplace; he’s simply refusing, as a religious conservative, not to sign up as an ally. He said they’re putting the screws to people in his company. This is a guy who is a mid-level executive who minds his own business, who gets along with everybody, who is scrupulously fair, but whose religious convictions won’t allow him to sign up as an “ally.” And he’s worried that this is at best going to cost him a promotion, and at worst cost him his job one day.

I was watching that great German film, “The Lives of Others” the other night, about the last decade of life in East Germany, and noticed how, in the opening scene, one of the students studying how to be a Stasi interrogator raised an objection to something he was being taught in class. The instructor, a Stasi interrogator, made a little note next to his name. Unreliable, that guy. A friend of mine, an immigrant from the Soviet Union, once told me that living there required you to develop a kind of schizophrenia. You had to always been on guard against giving anyone outside of your family and close, trusted friends the slightest indication that you deviated from the party line. The consequences for your career, and even your liberty, would be real and devastating. He told me that if you haven’t lived through it, you don’t know how badly it messes with your head.

Gay people lived through it in this country. So did black people. I’m glad those days are over, and may they never return. But justice does not require political and religious conservatives to have to live like that. That’s what it’s coming to, though, with this left-wing ideological policing, but explicit and implicit. “Cultural Marxism” is not just a right-wing buzz word.

So, I don’t feel a bit sorry for J. Bryan Lowder. All his protestations that he’s not like those awful conservatives (read: everyone the least bit to the right of J. Bryan Lowder, even liberals like Jon Chait), so the mob should leave him alone, won’t do him any good. Nor should it.

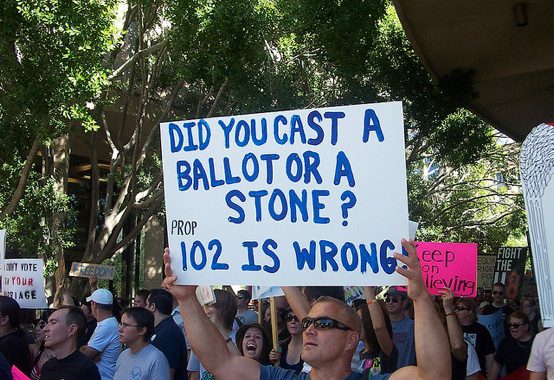

The Law of Merited Impossibility: It will never happen, and when it does, you people will deserve it. As a reader pointed out here the other day, that principle is becoming outdated. We’re getting past the “it will never happen” part.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.