Human Fallibility a Historical Constant

Run, don’t walk, to read Tish Harrison Warren’s great essay on “Our Beautiful, Broken Christian Ancestors.” Here’s how it begins:

I am a seventh-generation Texan who has ancestors from all over the South. When I think of the South, I see my grandmother’s hands, gnarled with arthritis—hands that picked and shelled native pecans and mastered a rolling pin. I imagine my great-grandfather’s dusty feet as he walked from Arkansas to the Gulf Coast looking for cheap land, a kid leading a milk cow. I think of live oaks and tall pines, Jekyll Island and the Blue Ridge Mountains, Walker Percy and Flannery O’Connor, bourbon and fried okra.

I also think of my ancestors from Mississippi—small-scale cotton farmers who owned slaves. I think of the graveyard where my parents will be buried, where, according to local lore, slaveholders and slaves are buried side by side. I think of Jesse Washington, a teenager who in 1916 was lynched an hour from where I live. I think of segregation, Jim Crow, and redlining. This, also, is part of my culture and story, even part of me, my blood, and my kin.

Both the North and the South practiced racial injustice, but in the South the legacy is unavoidable. Nearly as soon as they are old enough for moral reasoning, white Southern kids face this complexity: those before us who have committed atrocities also gave us life. Their legacies of goodness and evil are entwined.

At the heart of the broad, longstanding debate about the Confederate Flag on US public grounds lies a deeper question: How do we respond to evil in our history?

In the face of centuries of systemic racism, some Southerners have responded with a sort of ancestor worship, an idolatry of the past that makes us apathetic and defensive. Loyalty to those before us is exalted over love for those around us.

Clarence Jordan, a scholar and co-founder of the Koinonia Farm intentional community in Americus, Georgia, denounced this false worship. Once, after Jordan preached on the ministry of racial reconciliation, an elderly woman rebuffed him: “I want you to know that my grandfather fought in the Civil War, and I’ll never believe a word you say.” Jordan, a Southerner himself, replied, “Well, ma’am, I guess you’ve got to decide whether to follow your granddaddy or Jesus.”

It is a choice that we all face, wherever we are from, since we all inherit cultural and familial legacies marred by sin. But if the false gospel of some is ancestor worship, the false gospel of others is “progress.” We mobile urbanites can deride our heritage altogether. Confident in our own broad-minded superiority, we adopt a historical determinism that smugly labels everyone on the “right” or “wrong” side of history.

We might hope to avoid the complications of a shameful history by looking to the church as our true family. After all, Jesus scandalized the Israelites by elevating loyalty to the family of God above loyalty to biological families. He proclaimed that our true family is composed of those who obey God—the community of believers, the church.

But embracing the church does not rescue us from a painfully mixed legacy. It puts us right in the center of one.

Read the whole thing. Best thing you’ll read all day, I bet.

Where to begin with this? Let’s start with that last paragraph. Tish (who’s a friend) goes from there to talk about how every age of the Church has brought us saints and sinners alike. Reading her piece, I thought about how the same age that produced Dante and the Chartres cathedral also produced immense injustice (in fact, the Divine Comedy exists in large part as a rebuke to the corruption within the Church). The sins of another time and place are not necessarily the sins of our own, but we make a grave mistake to imagine that this means we do not sin. Our descendants will look back on things that we believe and do without thinking twice about it and marvel that we could have been so blind and wicked. And they, in turn, will suffer the same fate. To study the past with an open mind and an open heart is to be chastened about one’s own fallibility.

It’s the same all over, don’t you think? It is perhaps clearer for Southerners, because the evil of slavery and all that followed it was so stark, and still exists within living memory. I tell my children how things were here in our own town not that long ago, and they find it hard to believe. How could white people have believed those things? How could they have done those things? Well, I say, they did. And I try to convey to them in a way that they understand that they too might have believed and done those things had they grown up back then. This is the lesson of the Gospel account of Christ’s passion: every single one of us would probably have stood in that crowd yelling, “Crucify him!”

Every single one.

Yet it would be so easy if we could write off all our ancestors as simply evil. It saves us from having to do hard thinking about moral complexity, and about how goodness and evil can exist within the same person. The white Southerner who looks back at antebellum times and sees only white columns of the big house glowing in the moonlight, swathed in the scent of magnolias, is the flip side of the white Northerner who sees nothing but slavery and sin. Both are true.

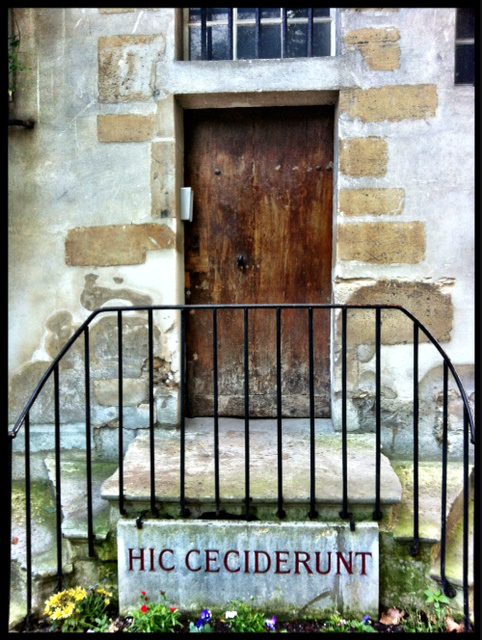

Three years ago, I was in Paris for the month of October. While there, I studied the French Revolution. I was staggered by the mindless savagery of the thing. You think you know about an event, and then you end up standing in the back garden of a Carmelite chapel in Paris, staring at a porch on which 150 priests were murdered, one by one, by revolutionaries, when they refused to renounce their beliefs. Here is that place; the plaque reads, in Latin, “Here they fell”:

These atrocities happened over and over again. And yet, when I read about the crimes of the ancien régime, with which the Church was complicit, it is not hard to see why the Church was so hated. In no way does this justify the atrocities, but you can grasp where they came from, in part.

I went to Versailles, which was extraordinarily beautiful … but also obscene, in its way. If you seek a monument to moral purity, you will find it nowhere. Everyone’s hands are historically stained. And so are our own.

I’m not arguing for moral relativism, not strictly. I think we can objectively say that Hitler’s Germany was more wicked than the France of Louis XIV. But we cannot say that the evil of Hitler’s Germany makes the France of Louis XIV a moral Eden. Nor can we say that the wickedness of the Jim Crow South absolves the contemporary South — or the North — of its sins.

It’s a simple, even simplistic, point, but it’s an astonishingly difficult one for many moderns to grasp. Tish talks about a time when her husband taught a class on the Church Fathers, and his students tuned him out because they regarded Augustine as a misogynist, the heretic Arius as a marginalized person, and so on. This is crackpot stuff. Think, by contrast, of the wisdom of Dante, a man who revered the Crusaders, but who put Saladin, the 12th century Muslim sultan who drove the Crusaders out of Palestine, in Limbo (the pleasant abode of righteous unbelievers), out of respect for his nobility of character. The great medieval Muslim philosophers Avicenna and Averroës are also there.

To be truly human requires a degree of cultural sophistication. We have to learn to judge rightly without ceasing to love what is lovable. Anyone who doesn’t live in some kind of tension with their people’s historical past is not being honest. I see a connection between the puritanical fanatics of ISIS, who are blowing up pagan ruins from antiquity in Syria, and those among us who wish to deny the complexity of the past by symbolically reducing it to rubble in our memories. The savage barbarian who dynamites the Temple of Bel and the civilized barbarian who dismisses Augustine because he had unenlightened attitudes towards women, differ only in degree.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.