Aunt Emily, the Southern Stoic

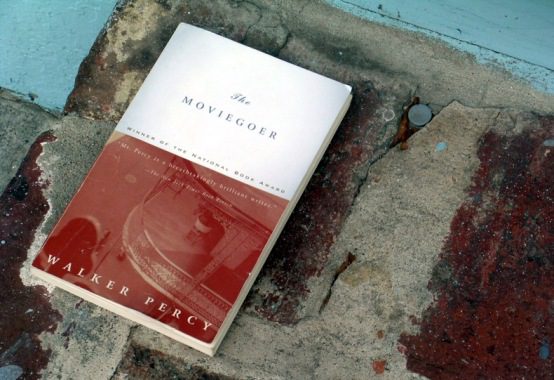

In Walker Percy’s novel The Moviegoer, the protagonist, Binx Bolling, is read the riot act by his old Aunt Emily, who is not a Christian but a sort of Stoic. Here’s her speech:

“Would you verify my hypothesis? Is not that your discovery? First, is it not true that in all of past history people who found themselves in difficult situations behaved in certain familiar ways, well or badly, courageously or cowardly, with distinction or mediocrity, with honor or dishonor. They are recognizable. They display courage, pity, fear, embarrassment, joy, sorrow, and so on. Such anyhow has been the funded experiences of the race for two or three thousand years, has it not? Your discovery, as best as I can determine, is that there is an alternative which no one has hit upon. It is that one finding oneself in one of life’s critical situations need not after all respond in one of the traditional ways. No. One may simply default. Pass. Do as one pleases, shrug, turn on one’s heel and leave. Exit. Why after all need one act humanly? Like all great discoveries, it is breathtakingly simple.”

Binx tells her he’s sorry he made her angry by his behavior.

“Anger? You are mistaken. It was not anger. It was discovery.”

“Discovery of what?”

“Discovery that someone in whom you had placed great hopes was suddenly not there. It is like leaning on what seems to be a good stalwart shoulder and feeling it go all mushy and queer.”

She tells Binx that it is a shock to discover, after all these years, that he is a “stranger” to her. And then, Aunt Emily lays it on him:

“All these years I have been assuming that between us words mean roughly the same thing, that among certain people, gentlefolk I don’t mind calling them, there exists a set of meanings held in common, that a certain manner and a certain grace come as naturally as breathing. At the great moments of life — success, failure, marriage, death — our kind of folks have always possessed a native instinct for behavior, a natural piety or grace, I don’t mind calling it. Whatever else we did or failed to do, we always had that. I’ll make you a little confession. I am not ashamed to use the word class. I will also plead guilty to another charge. The charge is that people belonging to my class think they’re better than other people. You’re damn right we’re better. We’re better because we do not shirk our obligations either to ourselves or to others. We do not whine. We do not organize a minority group and blackmail the government. We do not prize mediocrity for mediocrity’s sake. Oh I am aware that we hear a great many flattering things nowadays about your great common man — you know, it has always been revealing to me that he is perfectly content so to be called, because that is exactly what he is: the common man and when I say common I mean common as hell. Our civilization has achieved a distinction of sorts. It will be remembered not for its technology nor even it s wars but for its novel ethos. Ours is the only civilization in history which has enshrined mediocrity as its national ideal. Others have been corrupt, but leave it to us to invent the most undistinguished of corruptions. No orgies, no babies thrown off cliffs. No, we’re sentimental people and we horrify easily. True, our moral fiber is rotten. Our national character stinks to high heaven. But we are kinder than ever. No prostitute ever responded with a quicker spasm of sentiment when our hearts are touched. Nor is there anything new about thievery, lewdness, lying, adultery. What is new is that in our time liars and thieves and whores and adulterers wish also to be congratulated and are congratulated by the great public, if their confession is sufficiently psychological or strikes a sufficiently heartfelt and authentic note of sincerity. Oh, we are sincere. I do not deny it. I don’t know anybody nowadays who is not sincere. Didi Lovell is the most sincere person I know every time she crawls in bed with somebody else, she does so with the utmost insincerity. We are the most sincere Laodiceans who ever got flushed down the sinkhole of history. No, my young friend, I am not ashamed to use the word class. They say out there we think we’re better. You’re damn right we’re better. And don’t think they don’t know it–” She raises the sword to Prytania Street. “Let me tell you something. If he out yonder is your prize exhibit for the progress of the human race in the past three thousand years, then all I can say is that I am content to be fading out of the picture. Perhaps we are a biological sport. I am not sure. But one thing I am sure of: we live by our lights, we die by our lights, and whoever the high gods may be, we’ll look them in the eye without apology. Now my aunt swivels around to face me and not so bad-humoredly. “I did my best for you, son. I gave you all I had. More than anything I wanted to pass on to you the one heritage of the men of our family, a certain quality of spirit, a gaiety, a sense of duty, a nobility worn lightly, a sweetness, a gentleness with women — the only good things the South ever had and the only things that really matter in this life. Ah well. Still, can you tell me one thing. I know you’re not a bad boy — I wish you were. But how did it happen that none of this ever meant anything to you? Clearly is did not. Would you please tell me? I am genuinely curious.”

Binx can’t tell her, because he doesn’t really know. He is detached from the culture that gives Aunt Emily, thickly embedded in it, a sense of meaning. But then, he is detached from everything, a stranger to himself.

Aunt Emily’s soliloquy is bracing stuff. The mindset she talks about is the mindset in which I was raised, more or less. I mean, we didn’t have the aristocratic aspect (though ours definitely involved a moral aristocracy), and my father didn’t indulge in the philosophical aspects of his creed that interest Aunt Emily. But most of this is very familiar to me. It’s why I said in Little Way that my dad is more Stoic than Christian, motivated above all by a profound sense of Duty. My father never said these words to me, but I can hear his voice in Aunt Emily’s question: “But how did it happen that none of this ever meant anything to you?”

And I can hear myself in Binx’s half-answer: he says he didn’t reject it, really, that he listened and took it seriously, though he couldn’t accept it and live by it. There Binx has nothing else to say. In my case, I would have said that I recognized those values not as eternal verities, but as a matter of ethics, of custom, that came from a world in which I was not embedded. I thought they were a fine code, and mostly I live by that code. Better to live as Aunt Emily than to live as Binx, drifting through life aimlessly, avoiding commitments. But they are not enough. They are one-dimensional. For me, the Christian faith opened the door to life in its fullest dimension. It is only through passionate commitment to the Absolute that I can live by the Stoic code of my culture, which has only relative value.

Readers familiar with Kierkegaard — and Percy was deeply read in Kierkegaard — will understand what’s going on here. Encountering Kierkegaard in college gave me a framework to make sense of why I was in such despair over my Aesthetic mode of life, but could not accept the Ethical mode as the ultimate answer to my despair.

I bet some of you Southern-born readers of this blog recognize Aunt Emily…

And by the way, I recognize myself in Aunt Emily’s speech, at least a third of myself, anyway.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.