Social Security: Gut or Expand It?

Social Security has been running a deficit since 2010, and in 2034, its “trust fund”—more or less just a tally of previous surpluses—will run out. Left and right could not disagree more about how to handle the situation.

Democrats, up to and including Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, would like to expand the program, necessitating tax hikes above and beyond what would be needed merely to sustain it. And conservative intellectuals, whose thinking is captured in a new report from the American Enterprise Institute, would like to gut the program and replace it with a flat benefit that does nothing more than ensure seniors don’t live in poverty. That’s something the current program doesn’t achieve, so low-income seniors would see bigger checks—but on balance, this would slash benefits so dramatically that the program would eventually run a surplus, allowing tax cuts.

The left’s approach is grossly irresponsible. There is no compelling evidence that seniors, as a whole, need more benefits from the government—and in our current fiscal situation, they certainly shouldn’t be at the front of the line. But while the AEI plan has much to recommend it, it has zero chance of winning the support of the American people. The most likely and practical approach, alas, is the one Washington insiders have bandied about for years: A gentle mix of revenue and benefit tweaks to make the program sustainable.

The case for expanding Social Security rests on the notion that there is a “retirement crisis” plaguing seniors. The debate over this question can be mind-boggling in its scope: How much should seniors save for retirement? How much are they saving for retirement? Has the transition from “defined benefit” to “defined contribution” pensions undermined seniors’ financial security? On each of these questions, the relevant data are complicated and contradictory.

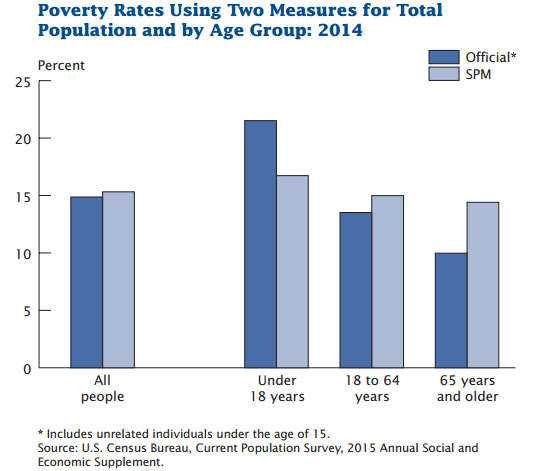

There are two simple ways, however, to illustrate the true plight of the American elderly. The first relies on basic poverty statistics. If we consider two different measures provided by the Census Bureau, those 65 and older are the age group least likely to live in poverty:

But maybe poverty rates don’t do a good job of capturing seniors’ financial situations. And maybe we’d like seniors to maintain their previous standard of living, not just stay out of poverty. After all, unlike a welfare program, Social Security pays benefits based on previous income, not need. Currently, it replaces 90 percent of a worker’s average monthly earnings up to $826, and progressively lower percentages above that.

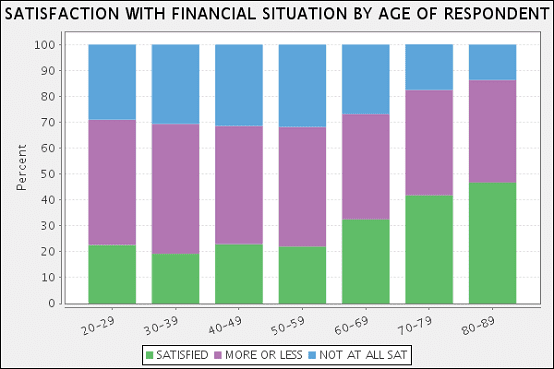

So instead, let’s just ask people if they’re financially secure. As Robert Samuelson of the Washington Post recently noted, the General Social Survey does this, and it reveals that seniors are the age group most satisfied with their current financial situation. The following chart combines data from the last three surveys (2010, 2012, and 2014), though the results are remarkably similar going all the way back to the 1970s.

The bottom line is that broadly expanding Social Security, while doubtlessly effective as a vote-buying strategy, would give more government money to the people who report they need it least. And as AEI’s Andrew Biggs—the think tank’s Social Security expert and the lead author of the new report—has pointed out, one curious element of most expansion plans is that they wouldn’t even eliminate senior poverty. Those who retire poor often haven’t spent much time in the workforce, and those who fail to work at least ten years currently don’t get any Social Security at all. If a private plan did this, it would be an illegally lengthy vesting period.

The AEI plan seeks to address this problem while bringing the program into fiscal balance. It would instate a minimum benefit at the poverty line, bringing the senior poverty rate essentially to zero. But it would also gradually reduce the program’s other payments, bringing those, too, all the way to zero eventually (2075). People wouldn’t lose benefits they’ve already worked for, but going forward, their payroll taxes would fund only a small, flat benefit. There would be a handful of more technical tweaks as well, including an increase in the early (but not full) retirement age and the elimination of the payroll tax at age 62.

Workers who wanted to maintain the current system’s benefits could do this by dedicating an additional 3 percent of their pay to a 401(k) plan, even if that plan earned very modest interest. To facilitate this, the AEI plan would make it easier for employers to set up 401(k)s, make enrollment automatic (a “nudge” that employees would have to intentionally opt out of), and also make the plans automatically adjust as employees age.

The plan should put a big smile on conservatives’ faces. It would scale back government’s intrusion into Americans’ retirement planning while actually doing a better job of alleviating senior poverty. The additional reliance on 401(k)s is somewhat frustrating—they’re a way of disguising government spending as a tax cut, they disproportionately benefit the wealthy, and the nudging has a distinct whiff of paternalism—but the changes to Social Security itself, which are highly progressive and cut spending, help to assuage those concerns.

And while it’s a debatable empirical question whether Americans would save enough to offset the cuts, well, that’s their problem: A nation as rich as ours should ensure seniors don’t live in poverty, but there’s no reason for taxpayers to guarantee a higher standard of living to people too irresponsible to put away their own money. Social Security’s assumption to the contrary has been wrong from the start, replacing personal responsibility and individual judgment with government confiscation of income for “safekeeping.”

The problem is that Americans won’t stand for the AEI plan. The authors themselves admit they took a “blank slate” approach, asking not how to save Social Security but how they would design it from scratch. Critics will say the plan “ends” the popular program, and they’ll be pretty much right.

More specifically, the plan is the opposite of the approach Americans say they want. A 2015 Gallup survey, for example, asked respondents to choose between tax hikes and benefit cuts for Social Security. Tax hikes won, 51-37.

In fact, the effort to expand Social Security probably stands a better chance. Entitlement programs tend to balloon with time—that’s one reason why America’s debt is set to grow to 100 percent of GDP by 2039—and seniors in particular turn out to vote when their benefits are on the line.

One survey asked whether we should “increas[e] Social Security benefits and pay[] for that increase by having wealthy Americans pay the same rate into Social Security as everyone else.” This is a misleading question—in fact, Social Security is progressive. (The rich do pay lower rates, but not low enough to offset the fact that the program replaces less of their income.) But the question showed the kind of rhetoric that advocates will use to promote expansion, and it resonated: 79 percent of likely voters, including 73 percent of Republicans, said they supported the idea.

The best conservatives can probably hope for is a modest shoring-up of the program. In an extensively poll-tested policy book a couple months back, for example, the centrist group No Labels suggested applying the payroll tax to income up to $240,000 (the current limit being $118,500), hiking payroll taxes by one percentage point for both employers and employees, slowing the growth of benefits for the top quintile of beneficiaries, and tightening up the requirements for disability. This would make the program solvent for 75 years, and it garnered 63 percent public support.

Maybe that isn’t precisely the right mix. But it’s probably a more sensible starting point than expanding or eviscerating the program.

Robert VerBruggen is managing editor of The American Conservative. Twitter: @RAVerBruggen

Comments