Why We Like Ike

Two years ago the Washingtonian magazine ran a lengthy investigation into the mismanagement of the proposed memorial in the nation’s capital to Dwight Eisenhower. Eisenhower was Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces during World II and the 34th president of the United States. He orchestrated D-Day, devoted more energy than any other Cold War president to trimming the obese defense budget, and tempered red-baiting hysteria. Yet as the Washingtonian detailed, the group devoted to establishing Ike’s memorial was mired in internal squabbles.

There is something darkly comic about the inability of the members of the Eisenhower Memorial Commission to manage their differences. Because, if nothing else, Eisenhower the man had a keen understanding of people and an agreeable nature. He was not a great battlefield general, nor was he a brilliant legislative strategist. But, as Liking Ike and Ike’s Gamble reveal in different ways, Eisenhower was remarkably shrewd in assessing human beings—both as individuals and as masses—and using them for his purposes. More often than not, those purposes were to America’s benefit.

Yet it is undeniable that Ike introduced some regrettable practices into American politics. Though John F. Kennedy is often remembered as the man who first exploited the power of television, College of New Jersey professor David Haven Blake establishes that it was his presidential predecessor who was the real trailblazer. “Guided by television pioneers and Madison Avenue advertising executives whom insiders dubbed ‘Mad Men,’ he cultivated scores of famous supporters as a way of building the kind of broad-based support that had eluded Republicans for twenty years,” he writes. Liking Ike is the most comprehensive treatment yet of the ways in which the two Eisenhower presidential campaigns launched the commodification of American politicians.

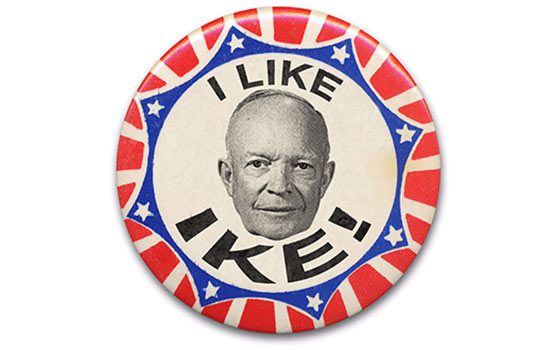

Jingles, commercials, televised endorsements, biographical videos—all were initially the products of the minds of New York ad agencies. Broadway performers took the stage at Madison Square Garden to gin up support for him, animators created television commercials, and Irving Berlin composed the song, “I Like Ike.” This large-scale manufactured enthusiasm all seems commonplace now, but employing the power of celebrity had never been done on this scale before Eisenhower. Warren Harding and Franklin Roosevelt had benefited from campaign appearances by entertainers, but television’s national reach made 1952 a watershed year for celebrity politics.

Eisenhower was the overseer of the merger of entertainment, advertisement, and politics. Perhaps it was inevitable that campaigns would realize the potential of television and treat candidates like any other product, to be packaged and sold and bought in large quantities. Blake repeats comically naïve statements from Eisenhower’s Democratic Party rival, Adlai Stevenson, and Stevenson’s campaign staffer George Ball. “They have conceived not an election campaign in the usual sense but a super colossal, multi-million dollar production designed to sell an inadequate ticket to the American people in precisely the way they sell soap, ammoniated toothpaste, hair tonic or bubble gum,” Ball complained in a speech called “The Corn Flakes Campaign.” But Eisenhower knew the influence that celebrities and novel products had on Americans.

♦♦♦

Eisenhower might have given us the notion of the televised candidate, but he couldn’t be accused of being without substance. More than just skilled at public relations, he was usually as clear-sighted abroad as he was at home. That is not the argument of Ike’s Gamble, however. Michael Doran’s book outlines an argument that has become increasingly commonplace in the press, if not in academia: that Ike took the wrong side during the Suez Crisis. He should have sided with America’s traditional allies Britain and France and future ally Israel in seeking to overthrow the Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1956. By failing to do so, Eisenhower “helped transform the Egyptian leader into a pan-Arab hero of epic proportions,” writes Doran.

Doran is a Hudson Institute fellow who served in George W. Bush’s Defense Department. His early 2002 Foreign Affairs essay “Somebody Else’s Civil War” is still among the best analyses of the 9/11 attacks. But Ike’s Gamble is remarkable for its poor research. Forget the kind of deep, multilingual scholarship conducted for a book like, say, Guy Laron’s Origins of the Suez Crisis; Doran does not even quote any of the English-language translations of Nasser’s works—or indeed biographies of Nasser—in making his assessments of the Egyptian leader’s thinking. “Nasser used the American fixation on peacemaking as a means of deflecting the attention of Washington from his revolutionary pan-Arab program, which screamed about Zionism and imperialism, but which also sought to eliminate Arab rivals to regional leadership,” he writes confidently, citing nobody.

Had Doran consulted the top works by or about Nasser, he would have been forced to reckon with the conclusions of scholars like Saïd Aburish, who believed that the Egyptian leader was actually “pro-American” but “wish[ed] to remain independent of all alliances.”

Ike’s Gamble suggests that Nasser was a uniquely brilliant and Machiavellian leader playing with well-intentioned but naïve Americans. Doran’s Nasser always knows the right thing to say to trick Americans—he always knows the right thing to do to manipulate foreigners in general. The consequences for the West were dire. “When Eisenhower took office in 1953, the Arab world was still tied to the West, thanks in no small part to the continued influence of British and French imperialism,” writes Doran. Ike’s weakness invited the Soviets into the Middle East, precisely the opposite of Eisenhower’s intentions. America’s foes were emboldened, and its allies weakened permanently in the Middle East.

If Ike’s Gamble were the only thing one had to go by, one would imagine that today the Soviets and Nasser’s Pan-Arab heirs are jointly enjoying the fruits of the Middle East while the West has accepted a subordinate place in world affairs.

Of course, that is the opposite of what has happened. “After the Six Day War, Arab nationalism’s slide toward political marginality became irreversible,” writes Adeed Dawisha in Arab Nationalism in the Twentieth Century. “And what stamped on it this sense of fatality was the fact that it was Egypt under [Nasser] that lost.” Little more than a decade after the Suez Crisis that Doran portrays as earth-shattering in its impact on Arabs and Westerners alike, pan-Arabism was a spent force. A few decades after that, the Soviet menace was nonexistent. Suez was but a temporary setback in the Cold War from which America and its allies emerged triumphant.

Ike’s Gamble is notably silent on the ideology that has rivaled Nasser’s pan-Arabism in the Middle East in the past 60 years: political Islam. Had Israel, France, and Britain defeated Nasser, the result would not have been a peaceful acceptance of Western dominance in the region. In thinking that Arabs would continue to accept foreign subjugation, Doran—in this book and in his other writings—drastically underestimates the power of anti-colonialism. Instead, Arabs would have opted for a different philosophy that offered them independence. Today political Islam has in fact replaced pan-Arabism and is far more threatening to U.S. security than Nasser had ever been.

As it happens, Eisenhower courted Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, finding them sufficiently anti-communist and a viable alternative to Nasser, who eventually outlawed the group after it tried to assassinate him. As detailed in Ian Johnson’s A Mosque in Munich, the U.S. actually funded the Brotherhood as it penetrated Europe, establishing mosques of the kind that would eventually breed anti-American jihadism.

As it happens, Eisenhower courted Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, finding them sufficiently anti-communist and a viable alternative to Nasser, who eventually outlawed the group after it tried to assassinate him. As detailed in Ian Johnson’s A Mosque in Munich, the U.S. actually funded the Brotherhood as it penetrated Europe, establishing mosques of the kind that would eventually breed anti-American jihadism.

All of this is absent from Ike’s Gamble, which treats world affairs like something that happens only among great-power diplomats and government officials. There is a nostalgia permeating Doran’s book for a time when leaders in Western capitals could decide the fate of tens of millions of foreigners. But that era is gone, and the United States still pays dearly for those instances when Eisenhower tried to counter nationalism in the Third World. The most fateful intervention was in Iran, where Ike approved a CIA-assisted coup against a democratically elected man who was far from a Soviet client. More than 60 years later, America is facing an Iranian regime more hostile than Mohammad Mosaddegh’s ever was.

At a recent panel in New York on terrorism, Doran suggested that Iran is America’s nemesis, spreading havoc across the Middle East and funding anti-Americanism worldwide. He failed to see the irony that our Persian problems are a direct result of the type of actions he prescribes in Ike’s Gamble. The days of Western imperialist dominance are dead, and the wisest strategy is not to try and revive them. Eisenhower knew this—because he knew people.

Jordan Michael Smith is the author of the Kindle Single Humanity: How Jimmy Carter Lost an Election and Transformed the Post-Presidency.

Comments