The Five Most Powerful Populist Uprisings in U.S. History

The 2016 election constituted one of the great populist uprisings of American history. A large segment of the electorate rose up against American elites and many of their underlying governing nostrums—globalism, lax border control, free trade, American military adventurism, a wariness toward nationalism, the cozy relationship between Big Government and Big Finance. It’s an open question whether President Trump, who ran against those nostrums, will govern as he campaigned. There are sound reasons to believe he will abandon many of his campaign pronouncements and meld his populist rhetoric with more establishmentarian actions. If so, his political story could become one of the great sleight-of-hand perpetrations of the American experience.

It may be instructive, in any event, to look at the other great populist uprisings of our history by way of a comparative analysis. Herewith then is a list of the country’s five most powerful waves of populism.

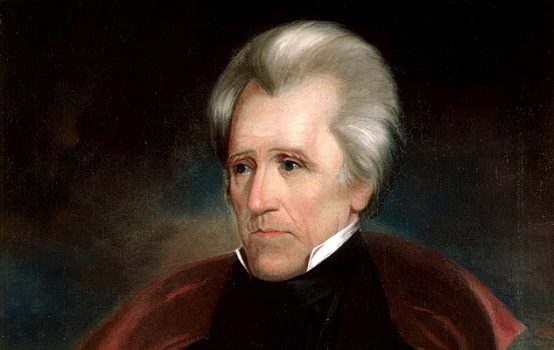

Andrew Jackson: We can’t understand Jackson’s populism without understanding how Thomas Jefferson set the stage for his emergence. The country’s first dominant party was the Federalists, unabashedly elitist in its advocacy of a strong federal government and a strong executive within that government. The greatest Federalist was Alexander Hamilton, who had argued during the Constitutional Convention that presidents should hold office until they died. Jefferson set himself foursquare against the Hamiltonian ethos. Following his 1800 presidential victory, he killed the Federalist Party and put to rest its brand of power consolidation.

But that irrepressible figure Henry Clay fashioned a successive political philosophy he called the American System—a governmental commitment to public works designed to pull the nation up from above. It included federal support for roads, bridges, canals, and even a national university. It also included high tariffs to plenish federal coffers (to pay for those public works) and to protect fledgling U.S. industries. It embraced the kind of national bank that Hamilton had fostered in his day. Finally, Clay wanted to sell public lands in the West at high prices to generate federal funds and bolster federal power.

Jackson opposed all this. He despised any concentrations of governmental power and didn’t feel the federal government needed to pull up the country from above. Let the yeoman thrive on his own, believed Jackson, and he would push the country up from below. Thus he favored selling land at low prices—or giving it away altogether—and he opposed the national bank, the national university, and federal support for projects he felt should be left to states and localities.

His big populist moment came when the 1824 presidential election was thrown into the House of Representatives (for lack of an Electoral College majority). There sat Clay, speaker of the House and the dominant figure in the chamber, who immediately maneuvered the members into giving the election to John Quincy Adams, a supporter of Clay’s American System. Jackson, who had garnered the largest plurality in both the popular and electoral balloting, was cast aside. But then Adams offered to Clay, and Clay accepted, the job of secretary of state, at that time the most unobstructed path to the White House.

Jackson went ballistic. For four years he railed against this “corrupt bargain,” as he called it. He employed rhetoric that included words such as “cheating,” “corruption,” and “bribery.” The elites had stolen the presidency, he thundered, and the people must seize it back.

Jackson’s thrust against Clay’s party unfolded amidst a subtle transformation in presidential politics. Until Jackson’s emergence, presidential elections had been largely in the hands of state legislators and other local men of prominence (elites), who selected the electors who in turn selected the presidents. Property restrictions also curtailed voter involvement. The idea was to keep the people at a distance from the process. But, responding to a wave of populism emerging in the west, more and more states were choosing electors by popular vote and eliminating property requirements. The result was the emergence of a mass electorate, a powerful new political force. Jackson brilliantly exploited this political force. Clay and Adams didn’t see it coming.

The result was that Jackson expelled Clay and Adams from the executive branch and installed in Washington his new populist thinking. As president, he reduced tariffs (but not as much as some of his followers wanted), terminated federal funding for a national road project, killed the Second Bank of the United States, sold Western lands at rock-bottom prices, and fashioned the yeoman class into a powerful political force. There was no more talk of a national university.

Jackson was the country’s greatest populist politician. He crafted a governing philosophy and a governing coalition that dominated American politics for a generation until slavery upended the old political fault lines and the Industrial Revolution brought forth the Republican successors to Clay’s American System. And note that Jackson’s populist emergence coincided with a significant shift in relative political power—the emergence of the yeoman class as a political force. Similar shifts in voting patterns also attended other major populist waves in America.

William Jennings Bryan: The 1890s were a bad time for America—and for Democratic President Grover Cleveland, who presided over one of the worst recessions in American history. A bubble in Western land prices had burst while surging grain production devastated farm prices. Farmers needed money to get through hard times, but there was no money. A deflationary spiral had ravaged the money supply. In the farm sector, the answer was simple: expand silver coinage to augment the money that traditionally had been backed by gold. The cry went up for the free coinage of silver at a particular ratio to gold, usually fixed at 16 to 1.

The establishment, consisting of some traditional Democrats and most Republicans, fought back, noting that the nation’s money supply had increased by 240 percent since 1860 and 104 percent since 1872—much faster than the rise in population. Also, they pointed out, global gold production had increased substantially in recent years, bolstering the money supply throughout the world. But the silver men wouldn’t hear of it. They were dying financially, and they demanded action.

This established the framework for one of the most intense populist waves ever seen in American history. It emerged in the 1896 presidential campaign under the banner of Nebraska’s Bryan, just 36 at the time, a lawyer and former two-term congressman but now a $30-a-week political commentator for the Omaha World Herald. Bryan calculated that if he could get to the rostrum of the Democratic National Convention he could sweep the delegates and take the nomination, notwithstanding that nothing of the sort had ever happened in American politics. He did get to that rostrum, where he delivered a breathtaking speech filled with political hellfire. He swept the convention and captured his party’s nomination.

It seemed for a time that he would sweep the nation, but it wasn’t to be. The Republican nominee, William McKinley, far more wily and calculating than most people at the time realized, deftly outmaneuvered the fiery Nebraska populist. He embraced the gold standard as a financial necessity but accepted the idea of greater silver coinage if other major nations would join in an international gold-and-silver agreement designed to prevent destabilizing currency speculations.

With this compromise concept McKinley managed to hold on to the Midwest and Northeast, traditional GOP strongholds, while Bryan swept the West and South. McKinley won with 271 electoral votes to Bryan’s 176. Then the new president further deflected Bryan’s populist wave, and bought valuable time, by sending a negotiating team overseas to explore an international currency agreement that would include expanded silver coinage. It didn’t succeed, but in the meantime McKinley managed to get the economy moving again. Prices rose, economic activity resumed, and the farm sector went back to planting and harvesting. When McKinley ran for reelection, he recaptured much of the West along with the traditional GOP strongholds of the Midwest and Northeast—and increased his electoral vote total to 292.

The Bryan populist movement turned out to be a flash in the pan—a powerful wave of sentiment unleashed by economic hard times but without the underlying force to sustain itself once the hard times were over. As president, McKinley placed the country on a strict gold standard while fostering strong and consistent economic growth. The populist silver surge was over.

1968: This was a year of convergence when numerous unsettling developments came together to rile large segments of the electorate—increasingly violent campus protests; bloody racial demonstrations in Northeastern and Midwestern cities with hundreds of deaths; a lingering war in Vietnam that the government couldn’t win and couldn’t end; landmark civil-rights legislation that upended old political alignments; and a quantum increase in federal power and governmental intrusiveness. The country hadn’t been so unsettled since at least the early Great Depression, perhaps not since the slavery debates of the 1850s. The violence outside the Democrats’ Chicago convention betokened the state of political affairs in a country filled with anxiety.

Into this mix strode former Alabama Gov. George Wallace, a kind of political bantam rooster who combined feisty rhetoric with a rustic humor. Although he made his name as a racial segregationist and that stamp never would wash away, he now was pushing much broader issues aimed at working-class Americans everywhere—an out-of-control federal bureaucracy, social experimentation such as school busing for racial balance, the lack of social cohesion, a breakdown in civic order. Wallace railed against “pointy-headed bureaucrats” who couldn’t park their bicycles straight. He said they proudly toted fancy briefcases to work, but when they were opened up it turned out there was nothing in them except tuna-fish sandwiches for lunch.

Wallace turned out to be largely a Southern candidate propelled by a distressed white power structure in that region, agitated by the looming rise of African-Americans through the 1965 Voting Rights Act. He carried five Southern states—Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia. But in collecting 13.4 percent of the popular vote overall he also helped demonstrate just how unsettled the electorate was. The unsettled voters gave the presidency to Richard M. Nixon by a paper-thin margin of just 510,314 popular votes.

The politically brilliant Nixon promptly set about to absorb this Wallace electorate into the Republican base. He did this through his much-maligned “Southern strategy,” decried by many as evidence that the GOP was employing an underlying racism to extend itself into Southern politics. But in the end the “solid South” gave way to a more normal brand of politics that accommodated the rise of serious black politicians, including governors and U.S senators, as well as solidly conservative sentiments similar to what was seen elsewhere in the nation. In the meantime, Nixon also galvanized large numbers of Northern working class voters—his so-called Silent Majority, upset by social chaos in the country—to score in 1972 one of the most lopsided presidential victories in American history. He lost a single state, Massachusetts, and the District of Columbia.

1992: In retrospect, it’s difficult to grasp just why the electorate was so unsettled in this year as to devastate a sitting president in the primaries and foster a third-party candidate who pulled nearly 19 percent of the popular vote (though he carried no states). Incumbent George H.W. Bush, successor to the highly successful Ronald Reagan, presided over an economy that, while in a mild recession, hardly left devastation in its wake. He had scored a major military success in forcing Saddam Hussein’s Iraq out of Kuwait.

But Bush had abandoned much of the Reagan formula, to the great consternation of many Republicans. He appeared a bit hapless on the economy, particularly in violating his own campaign pledge that he wouldn’t raise taxes. The Rodney King riots in Los Angeles, in which 55 people died, agitated much of the nation. And there was a growing feeling that the status quo in Washington was operating in its own interests far more than in the national interest and that rampant fiscal irresponsibility was threatening the nation’s future.

The first sign that this was going to be a populist year came with the New Hampshire primary, when commentator Patrick Buchanan (not even a real politician) scored 38 percent of the vote. He went on to collect 30 percent in Colorado, 36 percent in Georgia, 32 percent in Florida, and 27 percent in Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Massachusetts. Overall, Buchanan collected 23 percent of the primary vote.

That’s a devastating result for any sitting president and heralded the arrival of industrialist Ross Perot as an independent candidate. Perot entered the race with great fanfare, then exited the race in a huff, saying Bush had taken steps to sabotage his daughter’s wedding. He then re-entered the race and named as his vice-presidential candidate the retired Admiral James Stockdale, a former Vietnam prisoner of war and true military hero of rare dimension, who was, however, past his prime at this point and sadly out of place in the hurly-burly of American politics. Nevertheless, with all of that Perot still collected nearly a fifth of all popular votes cast.

Populist elections nearly always favor the challenger over the incumbent, and 1992 was no exception. Bush couldn’t withstand the anti-establishment sentiment of that year, and he fell to challenger Bill Clinton of Arkansas, who captured the far West and most of the Midwest and Northeast, as well as a smattering of Southern states. But it was the populists Buchanan and Perot who set the direction of American politics that year and destroyed the Bush presidency.

Trump: What we see in surveying the country’s five most powerful episodes of populism is that this sentiment stretches through the American experience, sometimes lying latent in the body politic, sometimes rising to the surface to redirect the course of politics when civic anger approaches or reaches a boiling point. But it is always there. It is worth noting, however, that seldom has the populist impulse actually captured a national majority or the presidency. It happened in 1828 with Jackson. And it happened only one other time, with Trump.

What this says about our own time is that we are in a period of superheated civic agitation, which isn’t going to go away in the same way that McKinley parried Bryan’s call for free silver coinage or Nixon co-opted the Wallace constituency. Trump may falter as president, may fail, but if he does, the American populism of our time won’t falter or fail with him. It will linger in American politics until the American system finds a way either to address the political agitations of our time or to somehow move beyond them. Either way, the unpredictability of politics will continue until the country manages to fashion a new consensus on who we are and where we’re going.

Robert W. Merry, longtime Washington, DC, journalist and publishing executive, is editor of The American Conservative. His next book, President McKinley: Architect of the American Century, is due out from Simon & Schuster in September.

Comments