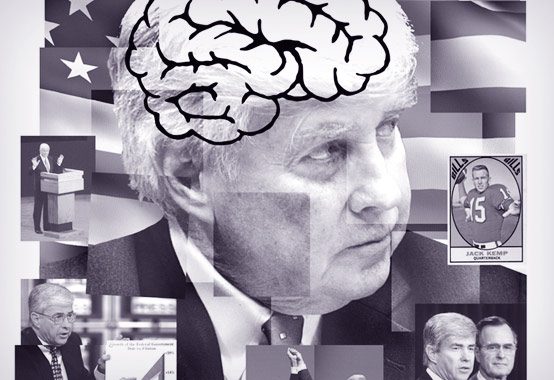

The Case for Kemp

Conservatives have long been looking for the next Ronald Reagan, when they ought to be looking for the next Jack Kemp, Reagan’s role model. Amid the malaise of the ’70s, Kemp devised a supply-side economic strategy that inspired a president and a generation.

He was arguably the greatest 20th-century Republican president America never had. Kemp, who died in 2009, first came to public attention as a quarterback for the San Diego Chargers and Buffalo Bills. In 1971, he entered elected office as a Republican congressman from the Buffalo area, and after a failed presidential bid in 1988 he served as secretary of Housing and Urban Development under George H.W. Bush. In 1996, he was Bob Dole’s vice presidential running mate.

But the résumé tells less than half the story—the greater part is told by the ideas, and the attitude, Kemp championed. He offered an optimistic vision tempered with realism at a time when America suffered from a stumbling economy, a weakening dollar, and dwindling confidence in government. Sound familiar?

His signature legislative achievement was the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981, the Kemp-Roth tax bill that kicked off Reagan’s supply-side revolution. But there was always more to Kemp’s vision than tax cuts, and what conservatives should take most to heart today are three of his overlooked lessons.

One is that the struggle between economic freedom and state capitalism is a worldwide conflict just as real as the clash between communism and the West once was. There is a home front in this struggle, but it also bears directly on America’s global power—and the second lesson is that economic strength is the key to long-term security. Kemp warned that war in Iraq would be wasteful and weakening. Leading the world by economic example was the way to preserve American prestige.

Finally, and poignantly, Kemp reminded Republicans that they must be free to criticize their party and accept the blame for their own mistakes. The partisan rancor of today’s discourse may be nothing new in American history, but it is distinctly at odds with the cheerfulness and charity Kemp cultivated throughout his career, and in which Reagan found such kinship.

In An American Renaissance: A Strategy for the 1980s, Kemp crystallized the challenge facing the GOP, then and now: “I happen to believe that our American renaissance requires … that we Republicans face up to the truth of our part in shaping the current national predicament. The hardest, most important step for Republicans to take is to recognize that we can’t go on blaming the Democratic Party.”

Can Republicans now admit that growth in government under George W. Bush contributed mightily to “the current national predicament”? Back in 2008, when certain banks should have been left to die in the ditches where they fell, the Bush response was bailouts. At the moment of testing, Bush gave up on the dynamo of the American economy: competition.

We still hear Kemp’s core ideas in the Republican Party’s rhetoric: a growth-oriented tax strategy, rewarding entrepreneurial effort, an emphasis on individual responsibility, energy independence, and reduced government spending. But the GOP’s incantation of this free-market mantra sounds hollow to recession-weary voters.

Recall how radical these ideas were when Kemp first articulated them. He warned an audience at Georgetown University in 1979 that ecological panic, government growth, and seemingly intractable foreign threats are all the products of a stagnant economy. Malthusian, redistributionist government thrives amid high unemployment and declining opportunity. And as the economy weakens, so does the country’s strength in the face of external challenges.

Kemp, who liked to call himself a “bleeding-heart conservative,” believed that America is not divided immutably into two static classes, but it is separated into two economies. One he called the mainstream democratic and capitalist economy, market-oriented and entrepreneurial. This mainstream economy rewards work, investment, and saving, and it provides incentives for productive behavior.

This was the economy of Reagan’s supply-side agenda, generating jobs, new businesses, lower inflation, and higher standards of living for most Americans. Rates were cut, but under the Kemp-Roth law federal income taxes paid by the top 1 percent of earners surged by more than 80 percent—to $92 billion in 1987 from $51 billion in 1981.

The other economy, Kemp explained, was similar in some respects to Eastern European or Third World socialism. It predominates in pockets of poverty throughout urban and rural America, with regulatory and cultural barriers to productive activity and a virtual absence of economic incentives and rewards.

Kemp argued that this economy particularly denies black, Hispanic, and other minority men and women entry into the mainstream. The irony is that this second economy—that of the welfare state—was born of a desire to help the poor, alleviate suffering, and provide a social safety net.

This economic division also applies globally. Kemp argued for a strategy of national defense built on economic strength—an approach to global affairs that does not reward corrupt leaders in other nations but instead maintains security by virtue of economic example. Kemp pointed out that in devising foreign policy Republicans had consistently ignored the plight of developing countries, leaving liberals to hijack the aid and development business, funding corruption and enemies. (Since Kemp wrote his plan, even some liberals have realized that the outcome of their efforts has been billions of aid dollars over several decades being wasted and fuelling endemic corruption in the recipients of American largesse.)

The military strategist Carl von Clausewitz wrote, “War is the continuation of politik by other means.” In today’s world, this means economic warfare: America can demonstrate leadership through economic success far better than by military intervention. The American Dream looks much more attractive when trading business contracts than it does facing down the barrel of a gun. In Kemp’s view, Bush got it wrong on Iraq, and he was reluctant to see the United States use military force there, writing in early 2003, “it would be a tragedy if a few War Hawks pushed us into an unnecessary invasion and occupation of an Arab country.” He worried that America would be viewed as the aggressor.

But what disturbed him most, he said on “Meet the Press” in 2006, was that there was no economic component to the War on Terror, no 21st-century Marshall Plan. “We’re not going to win this war with bullets and bombs alone,” he argued. “The ultimate challenge of the 21st century is to also use soft diplomacy and economic empowerment strategies in winning friends and allies in the Muslim world to the cause of freedom and democratic development.” Good economics creates free nations and more hopeful peoples. Bad economics, including the economics of military intervention, has the opposite effect—with serious repercussions for American security.

Today we are on the threshold of a struggle similar that of the Reagan years. This time the global enemy is not communism but state capitalism. With economic threats from India, China, and elsewhere, America must contend with new permutations of state capitalism rising out of the ruins of socialism and communism. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development estimates that state-owned enterprises worldwide have a combined value of almost $2 trillion and employ 6 million people.

In state capitalism, private enterprises find it enticing to partner with government, which boosts the power of the politicians and makes business an organ of the state—a new and virulent form of the socialist idea. It is becoming a formidable challenge to free enterprise. This is the real challenge to the nation, and the Obama administration has forsaken to meet it. Indeed, Obama promotes policies to advance state capitalism.

Kemp once asked, “Who is left to prevent the American Dream becoming a distant memory in an increasingly segmented, selfish, Europeanized politics—the kind of which Jefferson was so fearful?” Who indeed—is Mitt Romney the man to prevent this selfish and helpless Europeanization of American capitalism? Will the epoch of American capitalism give way to state capitalism, socialism by the back door?

Wisconsin Rep. Paul Ryan is frequently touted as a new Kemp, but his vision must be broader if he is to step into Kemp’s role. The New York congressman didn’t just stick to economic ideas; he painted on a broader strategic and historical canvas. A new Kemp will also need to master the diplomacy of reaching across the aisle without abandoning conservative principles. Kemp was a big believer in civility in politics, seeing the public arena as a contest of ideas. He was a vehement opponent of the politics of personal destruction—a stranger to the shoutfests that pass for political debate today. America will not be restored to health by such hardened hearts.

Wisconsin Rep. Paul Ryan is frequently touted as a new Kemp, but his vision must be broader if he is to step into Kemp’s role. The New York congressman didn’t just stick to economic ideas; he painted on a broader strategic and historical canvas. A new Kemp will also need to master the diplomacy of reaching across the aisle without abandoning conservative principles. Kemp was a big believer in civility in politics, seeing the public arena as a contest of ideas. He was a vehement opponent of the politics of personal destruction—a stranger to the shoutfests that pass for political debate today. America will not be restored to health by such hardened hearts.

Kemp desired “that history not say that in the American epoch the world was a seething despairing place. We have an idea that fathers prosperity and hope. It is time to offer it, not selectively, not grudgingly, but with confidence to a world that needs the human dream that grew up in America.” Aspiring Republican leaders must face up to the challenge of inspiring jaded voters with a similar message, if they hope to be more than parodies of Reagan.

David Cowan is completing a Ph.D. on the religious right and American foreign policy at the University of St. Andrews.

Comments