Portrait of the Artist as a Kidnapee

For most of us, the events of January 7th, 2015, are all too familiar. That morning, two gunmen stormed the offices of the satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo in central Paris. Wielding Kalashnikov rifles and invoking the Prophet, the men murdered twelve before fleeing in a black Citroën.

The subsequent fates of those gunmen are hardly important next to the shockwave that rippled through French society—where Charlie Hebdo was for many years something of a pariah—and which even lapped up, briefly, on the shores of America’s insular public discussions. (Though by now, the self-congratulatory Je Suis Charlie tweets and Facebook posts have faded away, only to be replaced by self-congratulatory boycotts.) Among the dead were some of France’s leading agents provocateur, including editor-in-chief Stéphane ‘Charb’ Charbonnier, who had spent decades needling diverse manifestations of piety, authority, and humorlessness—left or right, atheist or orthodox.

Indeed, as it turns out, overzealous imams had been a relatively minor target for the magazine. Better represented among the Hebdo regulars were reactionaries of the cast of novelist Michel Houellebecq, whose delightfully misanthropic depictions of modern society are soaked in disdain for the insipidness of life post-religion and post-sexual revolution. Fittingly, then, the issue of Hebdo in production on the day of the attacks featured a cutting caricature of Houellebecq. The writer is pictured as a shriveled husk of a man, donning a magician’s cap: In 2015, I lose my teeth…In 2022 I’ll celebrate Ramadan! The reference is to his latest novel, Soumission (“Submission”) a sort of near-futurist political allegory that envisages the peaceful takeover of French society by an ascendant Islamic movement.

Despite the predictable, almost rote recitations of outrage, the target of Soumission is not Islam at all, as Mark Lilla has eloquently explained. Rather, Houellebecq seems much more concerned with the moral and theological vacuum at the heart of postmodern Europe. Such emptiness leads to what Lilla calls a “sigh of collective relief” at the reemergence of an ideology capable of restoring transcendent order to a drifting civilization. Houellebecq agrees. “My book describes the destruction of the philosophy handed down by the Enlightenment,” he said in a recent interview, “which no longer makes sense to anyone.”

More than a slight exaggeration, perhaps. But Europe’s discomfort—and fascination—with Houellebecq can likely be traced to the fact that this diagnosis cuts much closer than we’d like to admit to the heart of our shapeless dissatisfaction in the midst of so much material plenty. It is not so simple to dismiss as mere religious prejudice—which is why it is so tempting to label it exactly that and move on. The fact that Houellebecq, if anything, would seem to be praising the lure of muscular Islam, at least in contrast with the West’s flaccid Christianity—”the Koran turns out to be much better than I thought,” he admits—speaks to the incoherence of these discussions.

In the meantime, Houellebecq’s dark prognoses for Western culture have won him plenty of readers (all the way up to President Hollande) but also a multitude of threats. His position is such that when, in 2011, he briefly disappeared from public view, there was speculation across French media that he had been kidnapped by al-Qaeda. (Or, perhaps, aliens.)

He soon resurfaced, citing nothing more sinister than a downed Internet connection. But the furor underscored not only the absurdity of celebrity but also the very real whiff of doom that wreathed Europe in the years following the 2004 Madrid and the 2005 London bombings. Hebdo‘s editor Charb felt this cloud acutely, declaring in the face of multiplying threats that he “would prefer to die standing”—and so, tragically, he did. Houellebecq’s dear friend, the incisive left-wing economist Bernard Maris, was also among those murdered at the Hebdo offices, reportedly sending the writer into a reclusive depression.

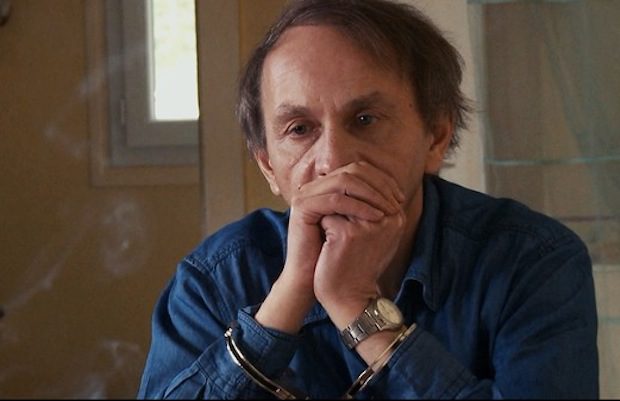

Morbidly timely, then, was the 2015 release of director Guillaume Nicloux’s “The Kidnapping of Michel Houellebecq,” a film that plays with the overreaction to Houellebecq’s 2011 disappearance. The plot asks us to imagine an alternate universe in which the abduction did indeed take place. Yet far from dwelling on the dark realities of terrorism, Nicloux’s film strikes out in another direction altogether—providing, instead, an intimate and often hilarious portrait of the writer that so many love to hate. It’s an entertaining look at Houellebecq’s personality—the dour scribbler plays himself with aplomb—as well as the anxieties that animate his work.

The film’s opening on Houellebecq’s comfortable Parisian life hits many of the expected notes. The writer attends Mass (“mostly funerals”), edits galley proofs, and dodges annoying acquaintances, ever chain-smoking and never far from a cup of wine. In conversations with friends, he denigrates Scandinavian aesthetics, compares modern architecture to the concentration camps, and dismisses Mozart while championing Motown. He is at once paranoid—spooked by a rough-looking cab driver—and resigned. When three strange men burst into his apartment, the frail author doesn’t much resist. The men stuff him unceremoniously into a metal box and cart him off to captivity at a rural farmhouse.

The kidnapping, like the rest of the film, is handled with a satirical touch. Though Houellebecq is convinced that death is near, the mortal tension soon dissolves as it becomes clear that the kidnappers are only middlemen, and quite amateur ones at that. Their initial disregard turns to curiosity at hosting such a notorious celebrity, and then warms to palpable affection for the crotchety old writer.

This reverse Stockholm syndrome drains the storyline of both danger and ideological charge—we learn that “It’s not the Jews or the Arabs” behind the plot, one of the only explicit nods to France’s ethnic tensions—and allows the film to proceed as comedy. But by deftly sidestepping the quicksand of shallow political commentary, it also opens up the narrative, unexpectedly, to an exploration of the defining qualities of Houellebecq qua novelist.

Bored by the tedium of “guarding” the impassive writer (and exasperated by his constant, grating demands for more cigarettes, better wine, and more interesting books) Houellebecq’s captors nonetheless unburden themselves like parishioners at confession. Despite his well-earned anti-social reputation, Houellebecq is deeply empathic. One kidnapper, a densely muscled MMA fighter named Mathieu (played by real life MMA fighter Mathieu Nicourt—the film eschews professional actors), quizzes him on how he gathers enough material for his books. “I listen a lot,” Houellebecq replies.

Literature turns out to be a favorite topic for these good-hearted meatheads. An emotionally fragile bodybuilder named Maxime (played by real life bodybuilder Maxime Lefrançois) receives a mini-lecture on writing poetry, with Houellebecq pontificating on the dangers of an entertainment-saturated age. “The most important thing is to get a bit bored,” he says. “If you do nothing, things will come to mind.”

“Can one create out of emptiness?” Max inquires.

“Yes—it is essential. A phone call can prevent me from writing. I must be absolutely empty.”

All of this to say that Houellebecq quickly becomes a sort of father figure for these men. Mathieu showing off his MMA fight videos, or Max demonstrating his bodybuilding poses, or the irritable ringleader, Luc, obstinately reciting his cloying sixth-grade poetry to the group’s general mockery—these are the exertions of sons starved for approval in a society that sees them as nothing but thugs, and that flatters itself that it has no more need for thugs. In a climactic scene, Houellebecq comforts a sobbing Max. “You break into tears because you know a word will soon come, one that’s too terrible to speak. For me that word is also father,” says Houellebecq, whose own parents abandoned him at a young age.

Meanwhile, the kidnapping also elevates Houellebecq into a son. He is all but adopted by the elderly couple, Ginette and André, who own the property. Soon they are eating dinner round the table each night like a real family—and bickering just like one, too. Houellebecq’s new tribe even celebrates his birthday with a drunken feast. And last but not least, the old man becomes a lover, falling into a melancholy (and, shall we say, financially facilitated) affair with a local woman. It is as though he is rushing to inhabit all of a man’s roles at once—making up for lost time, condensing a desperate fullness of life into mere days.

Nicloux’s comic narrative thus delivers a meditation on a deceptively profound subject: the alchemy capable of creating family out of thin air—and the tragedy that modern life has rendered this kind of magic both increasingly necessary and increasingly rare. His friends, his fame, and his posh apartment haven’t insulated Houellebecq from the bitterness of his own broken family. Such pleasures as he enjoys only seem to inflame his nihilism. Mathieu is alarmed to find at one point that the writer doesn’t care if he lives or dies: “I don’t believe in life very much,” he shrugs.

But by film’s end, Houellebecq has glimpsed a life worth living. “To be honest I would have liked to stay here longer,” he tells Ginette. “Does that surprise you?” Well, yes, it does a bit. For the author of “Submission,” the irony is clear: the novelist somehow experiences a deeper liberty in his captivity than in freely wandering the streets of Paris. It took a bizarre kidnapping to reorient him to a life in which the default state was something other than existential despair. As a believer might be tempted to say, God works in mysterious ways.

Which returns us, ultimately, to the problem of faith: both the grotesque excess—or, perhaps more precisely, deformation—displayed by the Hebdo murderers, and, at the other extreme, the hollow, jangling lack that seems to afflict most of the rest of us. But there is little sign that Houellebecq has been struck with any sort of Damascene conversion, despite his admission that his atheism “hasn’t quite survived.” His epiphany here is something altogether more prosaic. “After all this time, we know each other well,” replies Ginette, by way of goodbye. “I’ll miss you.” And just like that, Houellebecq is sent off, reluctantly, back to the lonely, comfortable boredom from which both the lyricism and despondency of his prose spring.

James Elliot McBride is an NYC-based writer and editor covering global affairs. He can be found on Twitter at @jelliotmcbride

Comments