No Hobbits Here

Many are the falsehoods of Melbourne’s “quality” newspaper, The Age. But perhaps the gravest appeared in a 1981 column by one Steve Harris, who assured Australian readers: “New Zealand. Just like home, really.” As well call Canada “just like America.” As well call Belgium “just like France.” As well confuse Maltese with Italians, conflate Portuguese with Spaniards, pretend that Channel Islanders are Englishmen, or likewise insult any small nation by supposing it to be coterminous with its nearby big nation.

Yet the attitude is one that my compatriots and I struggle to overcome, ex officio as it were. Granted that innate politeness prevents New Zealanders from calling their neighbors “gringos”—at least where we can hear them—a trip across the Tasman can foster the gringo element in even the most mild-mannered Australians. When the Times of London ran its December 1967 death notice for drowned Aussie Prime Minister Harold Holt, it described Australia and New Zealand as “countries that should be good friends but are not.” In that regard, little has changed almost half a century on.

New Zealanders speak fluent English, and their faucets disgorge potable water. They also, like Australians, drive on the road’s left-hand side and the car’s right-hand side. This prevents the social embarrassment inevitable when a negligent Australian visitor attempts to enter a Manhattan taxi through the door nearest the steering-wheel. (“Are you trying to hit on me, bud?”) As for the rest, even P.J. O’Rourke’s Holidays in Hell, surveying New Zealand, merely groups it with New England, Canada, and Costa Rica as “reasonably nice places.” Positively gushing, compared to P.J.’s infamously opprobrious National Lampoon gazetteer from 1976 about Australia: “The local dialect has over 400 words for ‘vomit’.”

I last visited New Zealand 33 years ago. In 1981, the island nation seemed still in shock from Queen Victoria’s death. The southern city of Dunedin then forbade Sunday trading altogether. A statue of John Knox loomed over a main Dunedin square to drive the sabbatarian point home.

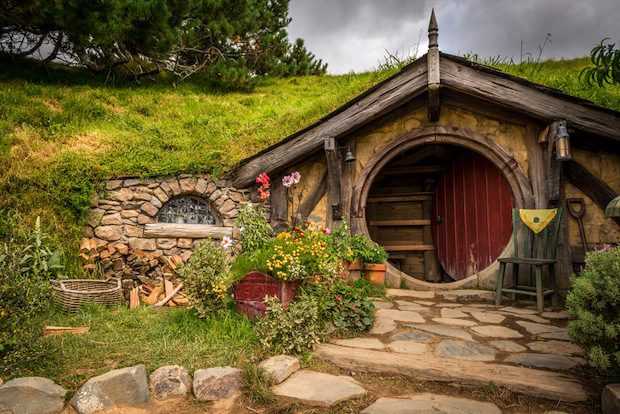

Today, New Zealand has completed the transition from an agriculture-based economy to a hobbit-based economy. If one consults the New Zealand Tourist Bureau’s URL—www.newzealand.com, simple enough for even the densest hobbitomanes to remember— obtaining non-hobbit-related information becomes an authentic challenge. The “desolation of Smaug” cited in the most recent Hobbit movie’s subtitle is as nothing beside the desolation of yours truly when forced to contemplate this stuff.

Abounding on the website are salutes on the general lines of: “You will experience a warm and generous welcome from New Zealand’s citizens, each of whom is 27 centimeters tall and answers to the name of ‘Frodo’.” Albeit Sir Peter Jackson might have released “The Fellowship of the Ring” as long ago as 2001, there still flourish innumerable Kiwis dining out on their 15 minutes of cinematic fame. Having achieved fully five seconds on screen as Aragorn’s garbage-collector or—during climactic battles—as the 17th orc from the right, they number themselves with the thespian greats.

New Zealand’s gentility has a sinister underside, in accordance with Salman Rushdie’s verdict on Adelaide as the perfect setting for a Stephen King novel. “Sleepy, conservative towns,” Rushdie maintained, “are where these things happen.” Consider the Juliet Hulme/Pauline Yvonne Parker killing on which Jackson based his film “Heavenly Creatures.” In 1954 two Christchurch schoolgirls, dreading enforced separation by the mother of one of them, eliminated said mother with 45 blows from a brick.

The global journalistic coverage of their crime attracted Truman Capote’s notice. Alas, Capote shed only with hardship his belief that the murder was Australian, telling Sydney columnist David McNicoll, “I thought you two [countries] were joined together.” Eventually he abandoned the Hulme-Parker matricide and concentrated instead on the 1959 massacre that produced In Cold Blood. At least Capote could find Kansas on a map.

Nothing remotely sinister befell me across the Tasman, but serious weirdness did on occasion manifest itself. The first steps into Auckland’s airport proclaim that a cultural revolution has taken place. Bilingual signs in English and in Chinese characters abound: “No spitting,” the English wording says. Clearly we are not, Toto, in Kansas anymore. Even if Capote was.

Talking of Toto, at Auckland airport’s customs depot two golden Labrador sniffer-dogs—sniffer-puppies, really—greeted us arrivals. They so visibly wanted to propitiate us that any intruding terrorist could well have had his face licked off. Beforehand, the passport-vetting section had kept me waiting for a grand total of 10 minutes, which would have been five minutes save for the fact that I accidentally lined up for the European passport holders’ booth.

At this section I forgot to collect my briefcase. With horror, I realized my oversight only when reaching customs. A uniformed young female customs officer, her grin broad, waved me back past the NO ENTRY sign through to where my briefcase rested untouched. No problemo. In Sydney or Melbourne, a comparable memory lapse would probably have inspired a S.W.A.T. team to shut down the entire building and possibly to taser me into unconsciousness.

Gradually Auckland reveals its most deep-seated cultural truth: “by England, out of Canada.” Auckland doesn’t seem to do level ground. Hence, a stroll from one’s hotel room to the nearest café provides as much cardio as your average middle-aged Aussie male can risk. Auckland’s traffic is dreadful, not just because over a million people now inhabit a town built for a few hundred thousand but because mass transit faces the geographical problems familiar from San Francisco, except worse. Each outing is up hill, down dale, and up hill again.

Do these pressures make Aucklanders snappish, curt, and impatient, like the stereotype of Parisians? They do not. In my entire stay, I failed to witness a single Aucklander being rude. Concierges, cleaners, waiters, sales clerks, airline officials: all treated me with a non-groveling benevolence of which, among Anglophones, I had hitherto assumed Americans alone to hold the secret.

The other deep cultural truth, more swiftly discerned than the first, is the remarkable role played by Auckland’s Maori residents. Auckland is home to six Maori out of every 10. Maori comprise one-seventh of NZ’s total population. Nothing prepares the Australian Innocent Abroad for this demographic. Certainly not the single-figure proportion of Australia’s populace which has Aboriginal background. Here the Canadian parallel is apparent—and has been much noted—with Maori performing in the national polity the same awkward function carried out in Canada by Quebeckers. Accordingly bilingualism, unimaginable in 1981, has made amazing strides in 2014. Airport signs now abound in Maori terms, as do bureaucratic documents more generally.

Before the 1980s, being a Maori cannot have been much fun. No official sanctions against Maori existed: no Jim Crow laws; no Afrikaner “separate development”; not even the pre-1967 restrictions on Aboriginal suffrage in Australia. Unofficially, things differed. During the Cold War, a dozen New Zealand politicians fulminated at UN and Commonwealth assemblies against B.J. Vorster’s, Ian Smith’s, and George C. Wallace’s white supremacism. Back at home, said pols cheerfully forbade their school-age Maori constituents to utter a word of the Maori language in any playground. They appear to have reasoned that, yes, their tanned brethren could play a mean game of rugby, but as for allowing the foreign minister’s daughter to marry one…

Nowadays, if a visitor may judge, that overt bigotry is dead. Time, the Soviet Empire’s collapse, the transmission of Bledisloe Cup rugby coverage into millions of lounge-rooms abroad, and Dame Kiri Te Kanawa—these factors have done more to soften racial attitudes than any statute could achieve. Repeatedly since the 1990s Winston Peters, a Maori, has been a kingmaker in NZ’s unicameral parliament and in a position to act on his Buchananite economic dicta. A Maori television network has long received government funding. There have been Maori Governors-General before; there will be again. And yet, and yet… before we break out the congratulatory Bollinger, caveats might beseem us.

To enter downtown Auckland’s souvenir stores is to find—as well as the predictable bland fridge-magnets of kiwis, tuataras, and other charming if introverted local animals—certain trinkets that would make a Klansman swallow hard. Some of these trinkets depict the local bipeds, not necessarily Caucasian, performing unnatural acts with sheep. Please remember: these are on sale in Auckland, not in some farming hamlet an hour’s drive from the nearest ATM. And the briefest Google search will unearth anti-Maori websites of an acidity that could strip paint. Sentiments that the most unrepentant Australian redneck would never dare voice about his own First Peoples crop up as jokes among various white New Zealanders. Let two gamey samples serve for all.

Q: What do you call a shotgun combined with a balaclava?

A: Maori contraception.

Or again:

Q: Where do Maoris lose their virginity?

A: On Crimewatch.

And no, I’m not going to tell you the answer to the question “How many Maoris do you need for a funeral?” My morals might be built on sand, but in this sand I must draw the line.

I lack space to eulogize Wellington, where the national library appears to surpass any analogous institution Australia can show, even if the airport houses mankind’s only known ceiling-suspended statue of Gollum. And I can do no more than touch on the organ recital I foolishly gave within four hours of arriving in Auckland, having discovered the hard way that even a trans-Tasman plane ride can induce jetlag. This heroically unmemorable occasion involved my playing to what I had been optimistically told would constitute an audience of five and was in truth an audience of three. Its venue was a beauteous Edwardian-era Methodist chapel. In Sydney or Melbourne it would long since have been turned into a parking lot, yet in urban NZ small, well-tended houses of Christian worship abound. Their owners take the trouble not merely to equip them with excellent organs but to endure the expense of keeping these organs in tune. New Zealanders must simply like churchgoing a lot.

For my loyal though almost nonexistent public I offered three pieces: a 17th-century French fanfare, a 19th-century German sonata movement, and an early 20th-century miniature by the stupendously talented composer-organist Marcel Dupré. This last work bears the Old Testament subtitle “I Am Black but Comely,” so in certain ethnic environments its performance might be contraindicated. My all-white trio of auditors tolerated the outcome, and I quit the console to the pleasant if scarcely audible sound of six hands clapping.

Awaiting nocturnal egress from Auckland—where had the security puppies gone?—I kept pondering one of Edmund Burke’s maxims and how well it suited NZ’s most obvious virtue: its sheer pulchritude. No photo can do more than hint at it. “To make us love our country,” said the greatest Irishman of all, “our country ought to be lovely.” Perhaps a North Korean dictator or a Donald Trump could wipe out every last trace of those NZ mountains and valleys and pastures that will break your heart if you allow them. It is hard to imagine lesser perils doing so. Sitting in the Auckland departure lounge, one can soon find oneself involuntarily updating an American poet’s homage to the blitz-ravaged England of 1940:

I am Australian bred.

I have seen things to hate here. Things to forgive.

But in a world where New Zealand is finished and dead,

I do not wish to live.

R.J. Stove lives in Melbourne, Australia.

Comments