Mr. Jefferson Comes Home

The edifying sight of Ron Paul calmly explaining the contemporary application of American Revolutionary principles to the smirking disbelief of the plastic men and 9/11 junkies of the Republican field calls to mind the reaction of the reprobates who unexpectedly encounter Kurt Russell in John Carpenter’s film “Escape from New York”: “Snake Plissken—I thought you were dead!”

Paul has re-introduced the Founders into American political discussion, whence they had been banished long ago by New Dealers who dismissed the “horse and buggy Constitution” and, more recently, by the rootless airport-lounge-souled Republicans who regard the Bill of Rights as outmoded in our global wireless blah blah blah world.

The revolutionary fuse is lit. Quick, to the wick!

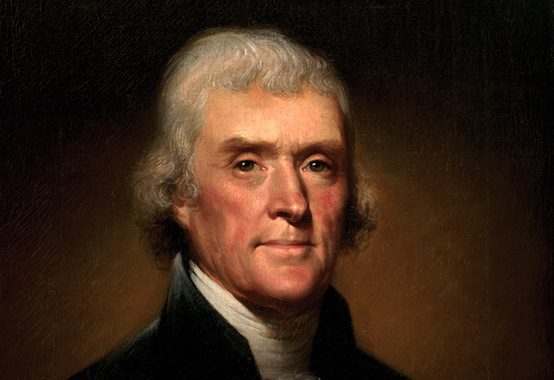

How wonderfully coincident that just as Paul is speaking the hauntingly resonant language of the early Republic, Alan Pell Crawford, Hoosier boy cum historian of his adopted Old Virginia, has published Twilight at Monticello: The Final Years of Thomas Jefferson, a superb and revealing study of Thomas Jefferson in retirement (if not ever repose) that makes Jefferson—the older, wiser, even more radical Jefferson—newly and provocatively relevant.

Crawford did his time on the Hill, working for Sen. James Buckley (“a genuine conservative”) and none other than Congressman Ron Paul (for whom he will vote). In 1980, he anatomized the swindle known as the “New Right” in Thunder on the Right, which made him, for a time, something of a darling of the liberal Left. He would later marry, raise a family, put down roots in Richmond—all those things the New Right claimed to support in those hysterical fundraising letters its bilkers-in-chief composed between cruises at the Brass Rail.

Crawford fell in love with Virginia, the Ancient Dominion, and in 2000 published Unwise Passions, an evocative study of the scandal-ridden Randolphs of Virginia.

Twilight at Monticellois Crawford’s best book and a humanizing corrective to the recent tide of Jefferson damning. This is Jefferson in his late autumn, brooding on the parlous state of republicanism, delighting in the presence of his family, tormented by boils on his backside. His death is rendered with especial poignancy. (In his final months, Jefferson used opium to allay a painful urinary ailment. Imagine the DEA breaking down the doors to Monticello! The medical marijuanans could do no better than to enlist Jefferson.)

Crawford excels at capturing the rhythms of life at Monticello, punctuated as they were by discord and disease, by debts no honest man could pay, by sottish in-laws and roistering Randolph relatives. He is affectionately amused by Jefferson’s penchant for theoretical agrarianism, noting that in the year of the ex-president’s elaborately planned “experimental” garden, Jefferson and his “family would rely to a remarkable extent on vegetables purchased from their own slaves, who grew them in far more modest garden plots alongside their cabins.”

Crawford is no white-washer. For instance, he concedes that the preponderance of evidence suggests that Jefferson fathered children by Sally Hemings, and his depiction of life at Monticello is neither Arcadian nor naïve. “I set out to prove Jefferson didn’t do it,” Crawford tells me of the conjugations with Sally Hemings, “just to be ornery—or at least to challenge what has become the conventional wisdom on the matter. I checked his health during the time of the pregnancies, for example, and he was fine. He suffered all sorts of ailments, but none when Sally got pregnant. The family alibis were unpersuasive, and then I realized that even if you believed them when they said it was Peter Carr, or Samuel Carr, or one of the Irish workmen, or Randolph Jefferson, you still had to conclude that all these men were having sexual relations with the slave women and that Jefferson’s daughter and grandchildren were aware of it. That’s how you had all those ‘yellow’ servants up there. The Hemingses weren’t the only ones.”

Jefferson never did reconcile his philosophical opposition to the “hideous evil” of slavery with the thing itself, despite entreaties by such Virginians as Edward Coles to act on his emancipatory convictions. Jefferson “simply could not imagine a realistic way to end” slavery and recommended instead a graceful and almost quietistic submission to regnant attitudes—“a position convenient for the slaveholder,” as Crawford notes, but “less so for the slave.” In the early 1840s, his grandson, Jeff Randolph, as governor of Virginia, proposed gradual emancipation and colonization (in Liberia) of Virginia’s slaves, which, despite the inhumanity implicit in the displacement of African Americans who were by then rooted, inextricably, in American soil, was one of the last real efforts to end slavery before the peculiar institution perverted the Southern Democracy into expansionist (Annex Cuba!) pro-slavery apologists.

Crawford’s Jefferson speaks to the current crisis in his late-life responses to the steady growth of the central state and the resultant erosion of the political role of the local citizen. Crawford emphasizes, as so few writers on Jefferson have done, the “ward republics,” Jefferson’s radical yet practical plan for decentralizing government. His “single most profound contribution to American political thought,” in Crawford’s phrase, was explicated in a series of letters in 1814-16. He proposed that almost all governmental powers devolve to “ward republics,” five or six miles square, which the country could rely upon for “the eternal preservation of its Republican principles.” Crawford abhors the enlistment of historical figures in present-day crusades, but Jefferson’s ward-republic idea, though firmly set in a place and time, offers us a way out of Empire—a path of refreshment, a revitalizing end to our torpid condition.

These wards were not air-traced abstractions. The Virginian had been deeply impressed by the town-meeting government of New England, which he called “the wisest invention ever devised by the wit of man for the perfect exercise of self-government, and for its preservation.” New England had stood fast against President Jefferson’s ruinous embargoes, and his successor’s War of 1812, such that Jefferson remarked, “I felt the foundations of the government shaken under my feet by the New England townships.” Allowing for the inevitable local variations, he wished to see the form and spirit of those townships replicated elsewhere.

We are accustomed, at this late date of American decay, to reading that the Republic is moribund. Jefferson harbored such fears as early as 1815, when he wrote that citizens exercise political power “only on the days of their elections. After that it is the property of their rulers.” As Crawford writes, “The steady transfer of power from the local governments to the states and from the states to the federal government threatened to turn all the challenges of self-government—of what later generations would call democracy—into problems of administration.”

The consequent enfeebling of the American aptitude for self-government would doom the Republic. “The virtues developed by participation in government would atrophy until Americans were no longer fit to govern themselves,” explains Crawford. “Losing any attachment to their liberties, the citizens would lack the will to resist their usurpation by ambitious men.”

Only by lodging the functions of government within the reach of ordinary people, by “giving to every citizen, personally, a part in the administration of public affairs,” said Jefferson, could Americans ward off “the degeneracy of our government” into, well, look around today.

This “gradation of authorities,” in Jefferson’s phrase, parallels the Catholic concept of subsidiarity. The national government, strictly limited to constitutionally prescribed duties, would oversee relations between the states and with foreign governments. The states and counties would tend to the limited number of responsibilities best handled at those levels, but the majority of tasks—police, roads, justice, militia training, elections, care of the poor—would be absorbed by the ward-republics.

The wards—that is, the parents, not credentialed educrats, not Department of Education consultants—would be responsible for the establishment and operation of schools. Think homeschooling consortia; think the old district system in America before the catastrophic wave of consolidation and rule-by-experts deprived parents of any voice in the education factories. To put the state in charge of education, wrote Jefferson, would be as mad as giving it “the management of all our farms, our mills, and our merchants’ stores.” (“A policy,” notes Crawford wryly, that “later generations of collectivists would endorse.”)

“To describe Jefferson during this period as an advocate of ‘states rights,’ to borrow the language of a later period, is to understate the case,” argues Crawford. “What Jefferson proposed was a radical decentralization of government itself.” States, hell—power to the neighborhoods!

The citizen of a ward-republic was to be no impotent voter, no cipher in the civil life of his community but rather “a participator in the government of affairs, not merely at an election one day in the year, but every day.” Catch the echoes in the idealistic strain of the New Left: this was participatory democracy.

Crawford also makes much, and brilliantly, contrarily so, of Jefferson’s draft “solemn Declaration and Protest of the Commonwealth of Virginia, on the Principles of the Constitution of the United States of America, and on the Violations of them,” which he submitted to his friend and fellow ex-president James Madison on Christmas Eve 1825. This document, which Jefferson drew up for the Virginia General Assembly, denounced as “usurpations” the federal government’s assumptions of powers not expressly granted by the Constitution. It denied that the general welfare clause created a government “without limitation of powers.” (The Anti-Federalists had warned Madison that it did this very thing almost 40 years earlier, but little Jemmy dismissed them as alarmists. Madison, timorous till the end, dissuaded Jefferson from forwarding his 1825 “Declaration” to the Virginia General Assembly.)

The Constitution, wrote Jefferson in his protest on behalf of Virginia, was a “compact” of coequal states. By “enlarging its own powers by constructions, inferences and indefinite deductions,” the federal government was shredding that compact. Jefferson did not threaten secession—not exactly. An “immediate rupture” of the union would be calamitous, but there was one calamity even greater: “submission to a government of unlimited powers.”

This protest against the loose construction and internal improvements of the John Quincy Adams administration is usually shrugged off by historians as the “soured” work of a “crabbed and distrustful old man” who was “smothered by localism,” as Leonard W. Levy characterized the elderly Jefferson. It is said to “reflect poorly on Jefferson,” says Crawford, and is derogated as the sad evidence of its author’s deterioration, of “a cramped, suspicious, and, above all, illiberal attachment to his native Virginia.”

Yet Crawford insists that Jefferson in his dotage was defending the same principles of liberty and local self-governance as had the young Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence and in the 1798 Kentucky Resolutions, which he had ghosted while vice president. The Kentucky Resolutions, written in protest of the Alien and Sedition Acts, insisted, “whensoever the General Government assumes undelegated powers, its acts are unauthoritative, void, and of no force.”

“Jefferson reiterated these principles throughout his life,” writes Crawford, “and it is surely evidence of their radicalism —and of Jefferson’s timeless relevance—that they retain their power to offend even now.”

Do you doubt it? Then witness the Paul maul. Speak for a decentralized, peaceful republic and the chickenhawks will peck.

“Real politics,” Crawford tells me in an interview, “isn’t possible at [the national] level or at this stage of history, at least through the official channels. We have crossed some line, and there is no going back. All that is left for the official channels to do is wage war, tax, manipulate, command allegiance, and engorge themselves. All real politics is done elsewhere, and it is an illusion to expect otherwise.”

“I can’t stand to hear Democrats and Republicans argue anymore, because it is a phony argument,” he continues. “They are merely competing for jobs. No good can come of it. Only the raw exercise of force and the subtler exercise of manipulation.” He singles out as illustrative the “significant moment when the professionals of both parties went down to Florida [after Election Day 2000] and took over from the Democratic precinct workers and treated them (as did the media) with utter scorn.”

“Power,” Crawford says, “is bad for a man and for everybody else. Presidential power allowed Jefferson to go to the wall for a stupid theoretical abstraction”—the embargo that galvanized New England. Crawford conceives of his subject not only as Jefferson but “the American presidency”—and he writes not in the Schlesingerian school of power worship but as a sympathetic profiler of the Jefferson who heartily distrusted “the consolidation of authority in the executive branch of government” and the “visceral desire for power itself.”

That Jefferson survives. We see flashes of his vision all around us today: in homeschooling and the small-schools movement; in community-supported agriculture, through which farmers sell to neighbors; in the rejuvenated music and literature of place. You hear its echoes in Ron Paul’s hopeful presidential campaign, in the peaceful hippie secessionists of the Second Vermont Republic, at farmers markets, and on small-scale organic farms. Home is being re-found, re-defended.

Not since the 1930s has the Jeffersonian vision seemed more congruent with the times. (Though that decade ended with the laying of the cornerstone of the Jefferson Memorial—the symbolic entombment of Jeffersonianism.)

By a happy happenstance, I read page proofs of Twilight at Monticello while preparing for a fine conference on the “Humane Vision of Wendell Berry,” sponsored by the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, the McConnell Center of the University of Louisville, and the Philadelphia Society. Berry—farmer, poet, novelist, essayist, Kentuckian—is no drawer-up of ten-point programs, but he does invokes Thomas Jefferson more than any other political figure, calling upon Jefferson’s wisdom to maintain—or reclaim—“farming, education, and democratic liberty.”

Berry’s poem “The Mad Farmer Manifesto: The First Amendment” uses Jefferson’s words as an epigraph: “it is not too soon to provide by every possible means that as few as possible will be without a little portion of land. The small landholders are the most precious part of a state.” To which Berry responds:

That is the glimmering vein

of our sanity, dividing from us

from the start; land under us

to steady us when we stood,

free men in the great communion

of the free. The vision keeps

lighting in my mind, a window

on the horizon in the dark.

That vision may have dimmed at times, flickering toward extinguishment, but it has taken on a new brightness of late. Jefferson lives!

____________________________________

Bill Kauffman’s books include Dispatches from the Muckdog Gazette and Look Homeward, America. His Ain’t My America is due out from Holt/Metropolitan in April.

Comments