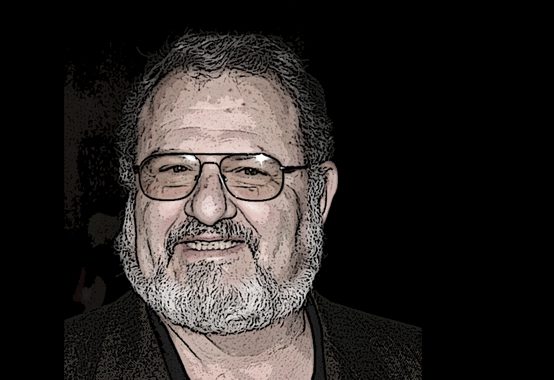

John Milius: A Real Wolverine

“I’ve been blacklisted as much as anyone in the ’50s,” says John Milius in the absorbing new documentary “Milius,” an aptly blusterous teddy bear of a movie directed by Joey Figueroa and Zak Knutson.

Milius, a self-described “Zen anarchist,” scripted some of the best films of the 1970s: “Jeremiah Johnson” (adapted from a novel by the cranky Idaho Old Rightist Vardis Fisher), “Apocalypse Now” (its title taken, explains Milius, from a button he had minted in the 1960s to mock the hippies’ “Nirvana Now” slogan), and “Dillinger” (starring the “constitutional anarchist” Warren Oates). His uncredited work includes “Dirty Harry”’s “Do you feel lucky?” street interrogation and Robert Shaw’s selachian monologue on the fate of the U.S.S. Indianapolis in “Jaws.”

Milius was at once a central figure and an outlier in the early 1970s Hollywood youth moment. Though personally close to the Midasian trio of Spielberg, Lucas, and Coppola, his firearm-based antics (such as bringing a loaded .45 to a meeting with a studio executive), as much as the masculine rite-of-passage motifs in his films, seemed to place him in that unpledged fraternity of directors with decidedly non-liberal politics: Michael Cimino, Walter Hill, Ron Maxwell, Clint Eastwood, Mel Gibson, Oliver Stone.

He completed the transition from colorful character to pariah, the documentary suggests, with “Red Dawn” (1984), which Milius cowrote and directed. “Red Dawn” is a Boys’ Life fantasy in which a gang of outdoorsy Colorado kids (nicknamed the Wolverines, after their high school mascot) resists the Soviet/Cuban occupation of their town. They run off to the mountains, sleep under the stars, play football, eat Rice Krispies for dinner, and draw up sorties in the dirt as if they were Hail Mary passes. It all sounds like a blast.

Despite the ludicrous premise, the film is filled with entertaining extended middle fingers (the occupiers use registration records to locate gun owners, among them the great Harry Dean Stanton, and throw them into re-education camps) that left conventional reviewers sputtering.

One of “Red Dawn’s” only thoughtful notices came from The Nation’s Andrew Kopkind, who saw it as a paean to insurgency, “a celebration of people’s war.” Milius, in this interpretation, is no jingo; he’s on the side of indigenous people fighting an occupying army. Kopkind’s essay is so good I can’t help quoting at length:

Milius has produced the most convincing story about popular resistance to imperial oppression since the inimitable “Battle of Algiers.” He has only admiration for his guerrilla kids, and he understands their motivations (and excuses their naivete) far better than the hip liberal filmmakers of the 1960s counterculture. I’d take the Wolverines from Colorado over a small circle of friends from Harvard Square in any revolutionary situation I can imagine.

As the Wolverines are about to execute a prisoner of war, one teenage guerilla asks, “What’s the difference between us and them?” To which the leader of the pack responds, “We live here.” The line might just as well have been spoken by a boy in Vietnam or Afghanistan or Iraq or wherever else imperialist superpowers alight.

My favorite Milius movie is his magnum opus manqué, “Big Wednesday” (1978), in which three surfers (the trifecta of Jan-Michael Vincent, Gary Busey, and William Katt) confront Vietnam, adulthood, and monster swells. Elegiac, evocative, excessive, “Big Wednesday” was a box-office wipeout, but since when is that a demerit?

The Golden Age of American cinema, the first half of the 1970s, had room for—nay, welcomed—this asthmatic, bombastic, gun-crazy Jewish surfer from St. Louis who said, “The world I admire was dead before I was born.” But today—Mistah Kurtz, he passé.

I despise Milius’s hero, Teddy Roosevelt, and I’ll bet we’ve never once cast a ballot for the same presidential candidate, but in our age of cringing yes-men and gutless herd-followers, who cannot admire a man who once explained himself to his fellow screenwriters: “I’ve suffered loss in my career for not being obedient. Believe me, the loss was little compared to the fear all you elite stomach every day. When the sun sets, I can sing ‘My Way’ with Elvis, Frank Sinatra, and Richard Nixon. What is your anthem?”

“To be a rebel is to court extinction,” said the booze-addled and self-dramatizing silent-screen siren Louise Brooks. John Milius is an authentic rebel, a true son of liberty, and in his 70th year his work is as alive as ever. And hell, I haven’t even mentioned “Geronimo,” “The Wind and the Lion,” or “Conan the Barbarian.”

Bill Kauffman is the author of ten books, among them Dispatches from the Muckdog Gazette and Ain’t My America.

Comments