‘Hamilton’ and the Romance of Government

I’ve finally heard “Hamilton,” the Broadway hip-hop musical about the first Secretary of the U.S. Treasury, and I can say: It’s a brilliant, empathetic example of a genre I don’t believe in.

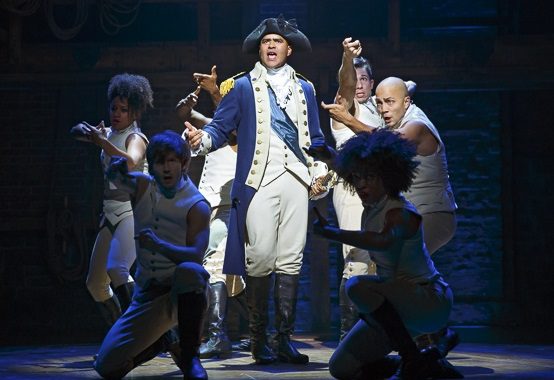

First the brilliance. I’m going only off the soundtrack here, since I do not have the ready cash to see the thing in person. Even in that silhouette form it’s obvious that Lin-Manuel Miranda, the composer, librettist and star, is ridiculously talented. In a little over two hours he gives you a sheaf of personalities, each with their own characteristic diction and each with their own angle. There’s Alexander Hamilton (Miranda) as a defensive, cocksure partisan, insecure and headlong, brilliant but occasionally showing the personal judgment God gave peanut butter. (But he’s reliable with the ladies!) There’s Thomas Jefferson, perfectly endowed by Daveed Diggs with chop-licking, insinuating, slightly camp villainry. There’s George Washington, the founding father in search of a foundling son; Aaron Burr, haunted and noncommittal. I can’t remember the last time I saw a romantic triangle as poignant as the unfought battle between the Schuyler sisters for Hamilton’s heart.

Better people than I can discern the countless references to musical theater and hip-hop history. (And here’s Ivan Plis on the accuracy of the show’s portrayal of insurgent warfare.) For my part I’ve just been sitting here running my fingers over the quotable lines: “Burr, you disgust me.”/”Oh, so you’ve discussed me!” “‘Should we honor our treaty, King Louis’s head?’/’Uh… do whatever you want, I’m super dead.'” “Daddy’s calling.” There are all the perfectly-placed comedy “Whaaaaaaat?”s and the rare but punchy cursing. There are the motifs, some of which are overdone–more on that in a moment–but others, like “not throwing away my shot,” which capture the musical’s themes of ambition and surrender. There are the little monosyllabic heartbreaks: “I couldn’t seem to die.”

There’s the seamless blending of hip-hop and Broadway, the upbeat choruses and back-and-forth battles. The grabby tunes (I’ve had the jazzy “Room Where It Happens” stuck in my head most of the day) and rippling internal rhymes. The stiletto jabs (“I hope you saved some money for your daughter and sons”) and clowning (“It’s hard to have intercourse over four sets of corsets”). And then those lines that are perfect, one side hilarity and one side pure night: “You’re an orphan. Of course! I’m an orphan. God, I wish there was a war!”

Miranda makes the outcome of the American Revolution seem uncertain again–not a history-book inevitability. He writes chaos and an unsettled narrative: This is a musical without a happy ending, because it doesn’t quite end at all. There’s tragedy for some, there’s the American experiment surviving, and, as in real life, the characters draw different lessons from their experiences. Miranda’s empathy shines in his decisions to give such a big role to Aaron Burr (“I’m the damn fool who shot him,” as he introduces himself) and to tell the climactic duel from Burr’s perspective. “Cabinet Battle #2” is also surprisingly evenhanded given how compressed it is: three perspectives in under three minutes. I loved the small, subtle touch that Washington sides with the other Virginians on the subject of home: Where they scheme for Virginia he longs for it. Whereas Hamilton, understandably, doesn’t get why people even care where the capital is.

I wish I could see the thing. I’ve tried to read a bit about the staging, but I know I’m missing some nuances of character and relationship: who jostles whom, who glances at whom in the thick of the action. I’m guessing the full experience is even more exuberant; I’ve heard that the stage production emphasizes the slavery/Jefferson connection even more, which seems like a cheap way of making heroes—more on this below.

There are a few small things here I don’t love, largely because they’re too beholden to contemporary styles of pop music and pop writing. “Farmer Refuted” is smug and dumb; hard to care when it’s followed by the brilliant “You’ll Be Back,” a creepy stalker ballad in which King George makes the case for rebellion better than these rebels could. Philip’s death scene starts out heartbreaking but dissolves into musical cliches: the quotidian childhood memory (“I taught you piano… You changed the melody every time”), the rote call-back (“Un, deux, trois”). A little fall of rain can hardly hurt him now!

There’s a deeper problem inherent in the musical, though. It’s not a problem about race exactly, although it becomes easiest to see if you approach it through race.

The racial cross-casting is one of the weirdest and greatest elements of “Hamilton.” There’s such exuberance in Miranda’s approach here, so much love of American history, such a winsome insistence that the American founding belongs to black and brown people as much as or more than it belongs to the rest of us. There are all these lines that show exactly why Hamilton’s life was made for hip-hop: “See, I never thought I’d live past twenty./Where I come from some get half as many.” You could hear that line from, to pick an especially resonant example, the Fugees.

But making Alexander Hamilton the representative from the socioeconomic margins requires certain elisions. Certain things must get hidden from the audience or deployed opportunistically. Slavery is a great cudgel to beat Jefferson with and God knows he deserved it, but if you’re looking for a reckoning with the fact of George Washington, slaveholder, you’ll get just that one hint at Yorktown: “Black and white soldiers wonder alike if this really means freedom” / “Not yet.” This is a musical in which the heroes end up in power, they make mostly the right choices and bequeath to future generations “a republic, if you can keep it,” and that is the victory underneath all the wrack of personal chaos, squabble, and grief.

This is the romance of government. And like all genre romance it relies on half-truths and evasions. It requires a belief that the right men in the right structures will make from power something worthy of our love—which sounds plausible until you realize nobody ever can come up with an honest example. For “Hamilton” to feel as vivacious and politically hopeful as it does, slavery has to be a to-be-sure, an aberration. You won’t see American Indians here, or actually-historically-black people other than Jefferson’s lovely cudgel Sally Hemings, because it’s hard to swoon for complicity. The show calls attention to the limits of historiography, the silences where nothing was written down or preserved–but the experiences of slaves become “the unimaginable” even more than the grief of bereaved parents.

You can argue, “You’re just saying Miranda should’ve made a totally different musical instead of the one he was actually inspired to make” and yes, that’s exactly what I’m saying. America is the shadow hero of this show—there’s that explicit analogy, “I’m just like my country/Young, scrappy, and hungry”—and while falling in love with a place is poignant and humbling, nobody should ever fall in love with a government.

In its own way I think my perspective is also hopeful, for what that’s worth. If George Washington and Alexander Hamilton were inextricably embedded in the structural sins of their own time and place then they are more like us, not less, and more available to us as a model.

If the American founding was mostly a romance then we have simply and colossally betrayed our chaste beloved. “The world turned upside down” and Donald Trump landed on top. If the American founding was one in a long series of rescue operations from which we turn out to need rescue, solutions made of problems, discoveries that hide things—then our problems are the eternal problems of power.

Lin-Manuel Miranda is smarter than me, and subtler, and in the end I think he proves me wrong about the ideals of his show by hiding an anti-politics beneath his politics. Maybe the most unexpected theme in “Hamilton” is that slowly-growing insistence on the need for surrender. It starts in “Helpless,” a gorgeous song where helplessness is a child’s terror but also a lover’s rapture. It builds through Washington’s counsel (“You have no control”) and farewell. Then Alexander’s advice to his son before the duel; and then Alexander’s own choice, to throw away his shot. The fake ideal America gives way to the inescapable individual choice for self or other. The hymn to power conceals a hymn to defeat.

Eve Tushnet is a TAC contributing editor, blogs at Patheos.com, and is the author of Gay and Catholic: Accepting My Sexuality, Finding Community, Living My Faith, as well as the author of the newly released novel Amends, a satire set during the filming of a reality show about alcohol rehab.

Comments