‘False Flags,’ Charlie Hebdo, and Martin Luther King

Seeking to explain recent terror attacks in France, conspiracy theorists have resorted to very familiar culprits: the Jews did it, specifically the mystical supermen of Israel’s Mossad. Such a theory is stupid and scurrilous, as well as on so many grounds self-evidently incorrect. That said, the Paris terror spree does raise significant questions about how we assign responsibility for terror attacks and what we can and can’t know by looking at the foot soldiers who carry out the deeds. Nor are debates over false claims and attributions wholly foreign to American history.

The most likely reconstruction of the Charlie Hebdo attack places primary blame on the Yemen-based al-Qaeda affiliate, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). Al-Qaeda wanted to carry out a spectacular in order to distract attention from the enormous successes enjoyed recently by its upstart rival, ISIS, in Iraq and Syria. Only thus, thought al-Qaeda leaders, could the group recapture some of its old momentum and credibility. Accordingly, two of the militants involved made a point of yelling their support for AQAP in the streets they had turned into a battleground. Their accomplice, though, who stormed a kosher market, was so far from understanding the wider agenda that he publicly proclaimed his own fealty… to the ISIS Caliphate. Oops.

In itself, the gulf between generals and foot soldiers is not hard to grasp. Even in regular armies, ordinary privates rarely have much sense of the broad strategic goals motivating their campaigns, although at least they can be sure about which nation they are actually serving. Such certainty is a luxury in terrorist conflicts, where individual cells and columns might find themselves contracting for a bewildering variety of paymasters. This degree of disconnect can be potentially useful for anyone seeking to manipulate a cause. A group can recruit uninformed militants as muscle to undertake a particular attack, which can serve wider goals utterly beyond the comprehension of those rank-and-file thugs. This might mean discrediting some other rival cause or else achieving a desired goal without suffering any direct stigma for committing the deed. Such pseudonymous actions thus offer deniability.

That brings us back, perhaps, to one of the most notorious crimes of 20th-century American history.

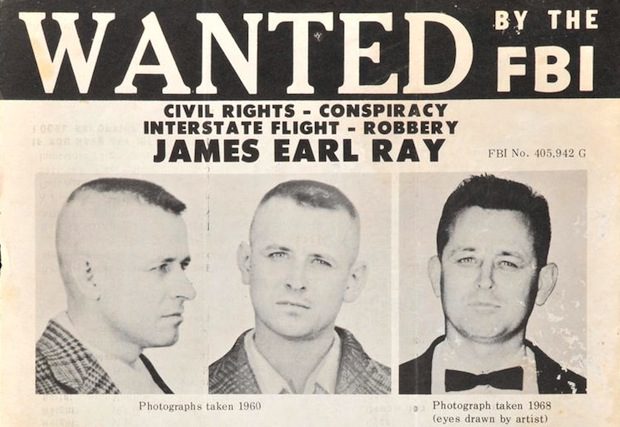

In April 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis. Despite multiple claims through the years, we can confidently say that the assassin was a petty criminal and armed robber named James Earl Ray, who fled the country before being arrested in London. Ray’s motives have been much debated, but a congressional investigation in the 1970s assembled extensive (if confusing) evidence that cliques of Southern racists and white supremacists had conspired to kill King, using Ray as a low-level subcontractor.

That might be true, but it is not what Ray himself admitted. In 2001, British authorities released information about the arrest and detention of Ray, material that has been largely ignored in the United States. During his British stay, he offered none of the lengthy defenses and denials of the shooting that he would later maintain. Rather, he talked freely about the King murder, and he even suggested the culprits who might have arranged the killing. Instead of white supremacists, though, Ray’s main candidates for the principals in the conspiracy were the Black Muslims, the Nation of Islam followers of Elijah Muhammad.

Let me say immediately that the fact that Ray said this does not of itself constitute weighty evidence for the existence of any conspiracy, let alone its nature. Ray, who died in 1998, was anything but a reliable witness. He was at best a contractor in the killing, and even the Ray family’s legal representatives spoke scathingly of the general intelligence of Ray and his circle. And the fact that Ray made such remarks does not even mean that he necessarily believed them. Perhaps he was making mischief.

Odd as it may sound in retrospect, though, the Black Muslim theory is not ridiculous, and it is quite as plausible as the white supremacist angle. We need to think back to a time when the U.S. had been racked by escalating race riots for several summers. Even responsible observers were forecasting outright race war, with cities partitioned between armed black and white militias. Radical black separatists stood to gain from a sensational act that would polarize and divide the races still further. Enlisting a white man to kill Martin Luther King would be a lethally effective form of dissimulation, and it was also wholly deniable. Elijah Muhammad had a track record of involvement in violence, and he is widely held responsible for ordering the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965.

If the London evidence had been better publicized in the 1970s, it would presumably have been more thoroughly investigated, and that might possibly have pointed to interesting connections. Lacking such an investigation, however, we really can add little to what is already known about King’s death: no reasonable person would build a new conspiracy theory solely on the shifting sands of James Earl Ray’s often-changing testimony. I am certainly not claiming any grand breakthrough in the case.

But from the point of view of terror investigations, the Ray affair contradicts so many of our regular assumptions. When individuals X and Y launch an attack, the media will direct all their efforts to determining what made them do it, and how they became so fanatically devoted to their cause. The problem is that the people pulling the triggers do not necessarily know much about the wider causes for which they are fighting. And what they do know might be totally wrong.

Philip Jenkins is the author of Images of Terror: What We Can and Can’t Know About Terrorism. He is distinguished professor of history at Baylor University and serves as co-director for the Program on Historical Studies of Religion in the Institute for Studies of Religion.

Comments