Democrats at War

The advent of Ron and Rand Paul sparked a necessary foreign policy debate within the Republican Party. But on issues of war and peace, civil liberties and national security, it is the Democratic Party that is truly a house divided against itself.

Consider: Colorado Sen. Mark Udall and Oregon Sen. Ron Wyden are two Democratic leaders of the bipartisan coalition to rein in the National Security Agency’s warrantless wiretapping. They are joined by Patrick Leahy of Vermont, the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

In the House, their position is supported by the progressives who have comprised the party’s peace caucus since the Vietnam War. These liberals joined with Tea Party conservatives to keep the country from bombing Syria earlier this year.

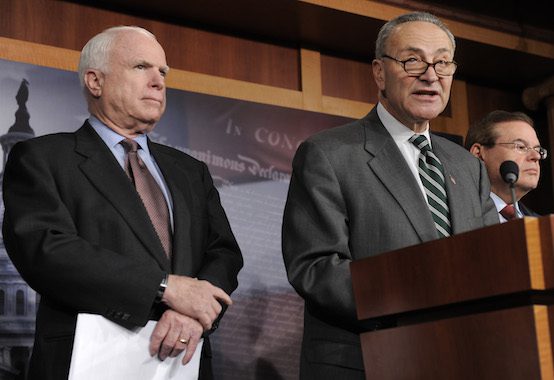

On the other side is the powerful New York Democrat Chuck Schumer, who helped recruit the party’s winning Senate candidates in 2006. Schumer has joined with Robert Menendez of New Jersey, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, to push for new sanctions with Iran despite an interim deal over Tehran’s nuclear program, negotiated by the Obama administration.

Not only do those sanctions threaten to derail the White House’s diplomatic efforts. Schumer and Menendez have joined with Republican hawks in insisting on zero enrichment, a bargaining posture as untenable as Iran insisting that the United States accept that the ayatollahs build a bomb.

Schumer was among the many Democrats who joined George W. Bush in the march to war with Iraq over a decade ago. Menendez voted, and subsequently campaigned, against that war. Both would be quick to argue that war is not what they want now.

But it is hard to see how their approach will lead to anything other than military action if we mean what we say about Iran’s nuclear ambitions. And contra John Kerry, war with Iran would simply not be “unbelievably small.”

Barack Obama himself represents the dueling tendencies within his party. At times, he has placed himself squarely within the Democratic tradition of liberal hawks: a surge in Afghanistan, military action in Libya, proposed military action in Syria, the acceptance of the Bush-Cheney national security state, the enhancement of his predecessors’ use of drones and surveillance.

On the other side of the ledger, Obama—who won the Democratic nomination in 2008 in large part because he opposed the Iraq war when Hillary Clinton did not—has not just attempted to jaw-jaw rather than war-war with Iran. Combat troops are out of Iraq. The president did not continue his Syria push after it became clear Congress and public opinion were against it, opening the door for weapons of mass destruction possessed by two of the region’s regimes to be dealt with by other means.

All and all, the president has yet to earn his Nobel Peace Prize. But it’s a far more prudent and restrained record than would have belonged to John McCain, and perhaps Mitt Romney. It may all come down to what happens with Iran.

None of this is new for Democrats. The architects of Vietnam shared a party with most of the antiwar protestors in the streets. The Democrats were the party of LBJ and McGovern, Jack and Bobby Kennedy. On the authorization of the use of force in Iraq, Senate Democrats split down the middle.

The same party that was once known for the “Democrat wars” of the twentieth century was by the 1980s associated with nuclear freeze and fecklessness in the Cold War. The Democratic senators who voted against the Persian Gulf War in 1991 saw their presidential ambitions evaporate the following year. Al Gore’s vote for the war helped land him on the ticket.

No sane political party should ever be generically pro- or antiwar. The justice and necessity of each military venture should be evaluated independently, in the context of the conditions and national interests at the time. But while the two parties advertise themselves as operating with different presumptions about the use of government at home, does either party start with a presumption of peace abroad?

It is an important question as the country confronts the possibility of war without end, with a battlefield that includes the homeland protected by the Bill of Rights.

It’s also something worth contemplating during the Christmas season. Few in Washington choose God over mammon. Still fewer the Prince of Peace.

W. James Antle III is editor of the Daily Caller News Foundation and author of Devouring Freedom: Can Big Government Ever Be Stopped?

Comments