Christian Thinkers Gather to Denounce Benedict Option

In my very first week of college, I was assigned to describe the best form of government. As a recent high school graduate, my only previous exposure to political philosophy was an AP Government revelation that the Founding Fathers’ famous phrase in the Declaration of Independence was borrowed from some guy named John Locke. So needless to say, I wasn’t particularly prepared to tackle the question mulled by philosophers for millennia. I did, however, know a few things: America was a democracy. And I liked America.

Indeed, my patriotism is the sort that’s sincerely stirred by the seemingly cliché crooning of Lee Greenwood, Aaron Tippin, and Brooks & Dunn. It’s no surprise, then, that this debut college paper turned out as a robust defense of democracy. Like most Americans, I simply figured that democracy and patriotism go hand in hand. To suggest a civic retreat from our democratic institutions, let alone entertain the merits of a non-American system of government, is completely foreign to the American experience.

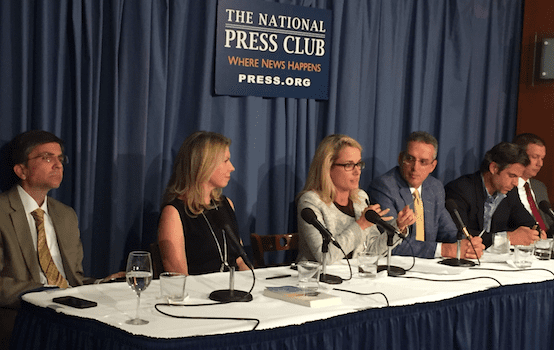

My eighteen-year-old self’s commitment to the American political experiment came to mind during a recent discussion on The Benedict Option hosted by the Institute on Religion & Democracy. Rod Dreher’s book, as readers of his blog in this space know, has elicited strong reactions from the American Christian community—both supportive and critical. The latter category was on display Wednesday evening in a lengthy conversation featuring adherents of diverse Christian traditions: Anglican Cherie Harder of the Trinity Forum, evangelical Alison Howard of the Alliance Defending Freedom, Joseph Capizzi of the Catholic University of America, Joseph Hartman of Georgetown University, and Bruce Ashford of the Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary. Despite the panel’s ecumenical nature, its members were more or less unified in their reluctance to endorse a Christian “retreat” from the public square.

Whether or not “retreat” is an appropriate description of The Benedict Option has been the topic of much debate, which I won’t rehash here. What the conversation revealed, though, is the extent to which American Christianity—both Protestant and Catholic—has become intertwined with political engagement. There are the obvious examples, such as Jerry Falwell Jr.’s full-throated endorsement of “dream president” Trump, and Robert Jeffress’ recent worship of the stars and stripes. But the visceral reaction to the mere suggestion of stepping back from the public square from many in the Christian ranks reveals the much more subtle ways in which our small-L liberal politics has effectively Americanized Christianity.

Of course, Christians have an obligation to engage in the political sphere, a point made convincingly by Alison Howard from the Alliance Defending Freedom. Howard argued that, were all Christians to take the Benedict Option, the bakers, florists, photographers, and the like who are served by ADF would have no defense against a rapidly secularizing culture.

But this contention, compelling as it is, reveals the difficulty Americans have with grappling with the heart of Dreher’s thesis. Howard’s objection presumes that there will continue to be a sizable number of bakers, florists, and photographers who will raise Christian objections to secularism throughout future generations. This implies, more broadly, that current American political culture is hospitable, or at the very least neutral, to the cultivation of orthodox Christian practice. Under this pretense, robust political engagement among Christians can make sense. The data, however, paint a foreboding forecast for Howard’s core presumption.

The work of Christian Smith reveals rapidly declining adherence to traditional morality among younger Christians. From The Benedict Option:

Smith and his colleagues found that only 40 percent of young Christians sampled said that their personal moral beliefs were grounded in the Bible or some other religious sensibility. […]An astonishing 61 percent of the emerging adults had no problem at all with materialism and consumerism. An added 30 percent expressed some qualms but figured it was not worth worrying about. In this view, say Smith and his team, “all that society is, apparently, is a collection of autonomous individuals out to enjoy life.” (emphasis added)

As the data show, a type of Moralistic Therapeutic Deism, in Smith’s words, has supplanted orthodox Christianity as the preferred faith within the ranks of the Church.

It’s the anti-BenOp response to these alarming statistics that gets to the heart of the matter. Many panelists were largely unalarmed by the apparent retreat from Christian mores among believers. Capizzi equated Smith’s findings with historically cyclical levels of religiosity and religious literacy. Hartman was “far more concerned about moralism [than] relativism,” charging that “we don’t need virtue, but grace, [since] the goal of Christian life isn’t virtue.” Harder decried Dreher’s “overemphasis on sexual ethics,” while Ashford connected political engagement to religious witness: “Declaring Jesus as Lord implies that Caesar is not.” To Christian BenOp critics, it seems, orthodoxy precedes orthopraxy; so long as we assert our individual, personal relationship with Jesus Christ, we’re largely protected from anti-religious aspects of culture.

Herein lies the incredible Amercanizing power of our small-L liberal political order. The individualism and de-emphasis of virtue on display in much of contemporary Christianity has deep roots in Western political thought and, in some important ways, informed the American founding. While individual salvation is far from foreign to historical Christianity, individualism—the promulgation of self over the bonds that tie communities together—is. Thus, both the Religious left and Religious right adhere to an American brand of Christianity underscored by the same prior commitments to “individual liberty” defined as freedom from restraint, rather than a traditional Christian understanding of liberty as freedom to do as one ought.

In this light, what’s offered in The Benedict Option is far from a neglect of civic responsibility. It’s a recognition that the powerful forces at the very heart of our political culture are capable of de-Christianizing the Church; it’s a roadmap for the fulfillment of civic responsibility in an authentically Christian way. If we are to fulfill this civic responsibility as Christians, we must first preserve Christianity from our political culture. Whether or not the Benedict Option is the best response to the challenges of our political culture is a legitimate debate. But to have this debate, it’s crucial that we understand the fundamental ways in which our politics affect the Church—rather than simply reaffirming American democracy out of a misplaced, albeit sincere, patriotism.

Emile Doak is director of events & outreach at The American Conservative.

Comments