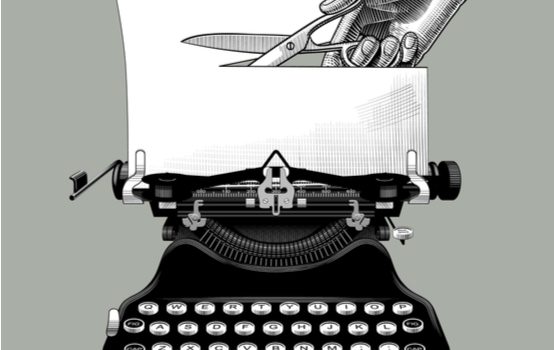

Censorship Tale

Among the centennial anniversaries not being observed this year is that of the free-speech martyrdom of Robert Goldstein, whose persecution led to the deliciously—and ominously—named federal case of United States v. The Spirit of ’76. (One guess as to who won: it’s the same side that’s been winning for the last hundred years.)

Robert Goldstein was a dreamy Los Angeles costumer who had supplied Abe Lincoln with his top hat and the Kluxers with their sheets in D.W. Griffith’s epic Birth of a Nation. Bitten by the movie bug and determined to outdo Griffith, Goldstein produced and directed his only film: The Spirit of ’76, an opulent—or so it is said; no prints survive—celebration of the American Revolution.

Goldstein, a native San Franciscan, said he hoped to make a “patriotic American Yankee Doodle Dandy, Wave the American Flag” silent blockbuster. Instead, as film historian Anthony Slide writes, he provided “a frightening reminder of how tenuous is the dividing line between freedom of speech and officially sanctioned censorship in the United States.”

As auteur, Goldstein tended toward melodrama: stirring patriotic tableaux of Independence Hall and Valley Forge alternated with scenes of Redcoat savagery, including an implied rape and the bayoneting of an infant in his cradle. But, hey, it’s only a movie.

The film opened in Chicago in May 1917 to favorable notices—except from Metallus Lucullus Cicero Funkhouser. With a name that could have come from a Coen Brothers movie, Major Funkhouser, Chicago’s police censorship czar, ordered the removal of scenes depicting the British in a bad light.

Sure, the Brits had been the enemy in 1776, but just a month prior to The Spirit of ’76’s opening, President Wilson, who had been reelected in 1916 on the slogan, “He Kept Us Out of War,” had dragged his countrymen into the European abattoir. We were at peace with our esteemed ally England.

In November 1917, The Spirit of ’76 opened in Los Angeles. Defying the censors, Goldstein restored the expurgated scenes in a brave and precocious instance of a Director’s Cut. Federal agents seized the movie and arrested Robert Goldstein for violating the Espionage Act. The Spirit of ’76, according to the indictment, was “intended to arouse antagonism, hatred, and enmity between the American people … against the people of Great Britain.”

Goldstein was tried, found guilty, and sentenced to 10 years; he served three and exited prison a broken man: impoverished, embittered, and maybe a touch mad. But, hell, wouldn’t you be? For making a patriotic film, Goldstein had been caged as an enemy of the state and been slandered, without evidence, as a tool of the Kaiser. Photoplay called him a “bumptious ignoramus, more fool than villain, who mistook greedy aggressiveness for talent and business energy.”

(Buffalonian John Lord O’Brian, a Charles Hughes Republican working in the Justice Department, persuaded the obdurate prig Wilson to commute Goldstein’s sentence. As O’Brian explained his politics during an unsuccessful run for the U.S. Senate in 1938: “The true liberal is tolerant of friendly criticism, full discussion and he believes in a government resting upon the power of persuasion and not on compulsion or coercion or other forms of restraint. Those at Washington would reverse the meaning of the word liberal. For in their view a liberal is a yes man, who gives blanket approval to all acts of authority.” As usual, America suffered by not listening to a Western New Yorker.)

Goldstein the ex-con reclaimed his film and exhibited it briefly in 1921, to jeering reviews. Despondent, he decamped for Europe, vainly hoping to reenter the movie business. With impeccably bad timing, the Jewish Goldstein found himself in 1930s Germany, jailed for lacking the money to renew his passport. He fled before war and Holocaust came down; it seems he died, anonymously, in America.

In 1927, Goldstein mailed a rambling account of his travails to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. He concluded:

Is it right that Robert Goldstein should be so persecuted for 10 years because he made a motion picture on the American Revolution? Is it so hard for Americans to admit that they have done this injustice? Or must he be driven to desperation and death before then? This is his punishment for depicting the origin of his country.

The grossest violations of the right to free speech in our history occurred under Woodrow Wilson’s war on the First Amendment, but the victims—radical farmers, Wobblies, intransigent Midwesterners, and a kooky idealistic movie producer—didn’t have press agents to apotheosize them, as did the rich communist screenwriters of the 1950s. So Dalton Trumbo is immortalized while no one even knows where Robert Goldstein is buried.

Bill Kauffman is the author of 10 books, among them Dispatches from the Muckdog Gazette and Ain’t My America.

Comments