Casualties of Waugh

Evelyn Waugh died in 1966 and spent most of his last two decades wishing he had died in 1946—or better still in 1446. His numerous latter-day foes shared this wish, often risking the full might of British libel laws in their zest for mocking him. Scottish journalist George Malcolm Thomson compared Waugh to “an indignant White Leghorn” and charged one of Waugh’s ancestors—on no evidence—with having left the Presbyterian church in protest against its abandonment of witch-burning. The late Hugh Trevor-Roper, now far better remembered as preposterous dupe (especially apropos the “Hitler” diaries) than for the historian’s role in which he fancied himself, was driven to new heights of sectarian cackling by Waugh’s creed: “Follow me, says Mr. Evelyn Waugh, for in the intellectual emptiness of modern English Catholicism only the snob-appeal is left.”

High-octane invective continued when Waugh could no longer fight back. An anonymous Time correspondent chose to summarize him as “a flabby old Blimp with brandy jowls and a menacing pewter complexion,” these traits being presumably considered adequate reasons for ignoring Waugh’s actual work. In 1982, Kingsley Amis—having several times winced under the birchings of Waugh as reviewer—retributively subjected Waugh’s most lush and baroque novel, Brideshead Revisited, to a triumph of silly-clever debating-society rhetoric predictable from its name alone: “How I Lived In A Very Big House And Found God.” (Previously Malcolm Muggeridge had dismissed the same book—which he never finished reading—as “tedious and rather foolish.”) And thence to one Jonathan Raban, who in his 1987 volume For Love and Money sniffed that Waugh, save for his novelistic skill, “might have been most happily employed in the writing of pamphlets for the Catholic Truth Society.” (So there.)

Even those who venerated Waugh often misconstrued him. Frances Donaldson, his neighbor and friendly enemy, lamented, “Often his jokes fell by the wayside, were not recognized as jokes.” A polite, if clueless, female newspaper interviewer from Stockholm told him, “Mr. Wog, you are a great satyr.” “I assure you not,” Waugh replied. Imperturbable, the Swede droned on, “My editor says you have satirized the English nobility.” (The interview’s dadaist tone, exemplified here, culminated in its eventual headline: “Huxley’s Ape Makes Hobby of Graveyards.”)

True, Waugh could famously dish the dirt in return. London’s literary Mafiosi—who, to the limited extent that Catholicism had come to their attention at all, associated it with Chesterton’s constant benevolence—quickly learned to quail at Waugh’s excoriating Catholic tongue. He denounced Britain’s 1945-1951 government as “the Cripps-Attlee terror.” In public he indicted the entire American people for bearing an extra dose of original sin: “treason to the British crown.” Edmund Wilson, whose Memoirs of Hecate County had been considered too salacious for British release—thereby feeding Wilson’s fantasies of himself as a pure Whitmanesque martyr assailed by dirty-minded Tory philistines—never forgave Waugh for his unsolicited counsel: “Mr. Wilson, in cases like yours I suggest publication in Cairo.” He famously greeted the removal of Randolph Churchill’s non-malignant tumor with the verdict: “It was a typical triumph of modern science to find the only part of Randolph that was not malignant and remove it.” And he scattered Trevor-Roper’s pretensions with a New Statesman outburst: “On the rather frequent occasions when he tries to make fun of our religion, he sets us the amusing weekend competition of spotting the first howler. We seldom have to read far.” Late in life, during the Second Vatican Council’s alleged golden dawn, Waugh received an invitation to a book launch by self-consciously “progressive” Catholics. He shot back by postcard his unforgettable RSVP: while he would not attend a social meal in the progressives’ company, “I would gladly attend an auto da fé at which your guests were incinerated.”

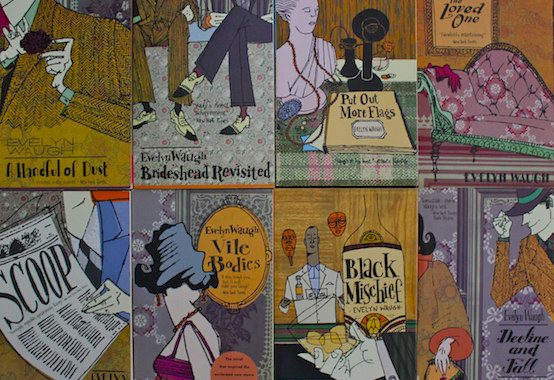

Abundant as Waugh’s output is in such pleasures as these, it seems ludicrous that whereas Waugh’s novels (especially the prewar ones) fascinate movie directors and appear to have provoked analysis from every critic and his dog, Waugh’s nonfiction remains an underrated treasure. He despised it himself, or rather, affected to despise it, scorning his collected journalism as “beastly little articles.” And if you believe that—to quote the Duke of Wellington—you will believe anything.

* * *

Born in 1903, raised in the Church of England, and a Catholic from 1930, Waugh produced (discounting forgettable juvenilia) his first essays in 1928, his last in 1965. Editors on both sides of the Atlantic—particularly at Life, Esquire, and National Review in the States, The Spectator and The Tablet in Britain—ran his commentaries with relish; unlike certain more pretentious sages, he demonstrated the humdrum virtue of submitting prompt and accurate copy. (For The Tablet he wrote unpaid, so greatly did he esteem its then role as guardian of Catholic doctrine.)

Since the Australian academic Donat Gallagher compiled in 1983 a breathtaking 662-page compendium of Waugh’s occasional prose, there goes our last excuse for not exploring it.

Among the several Waughs whom Dr. Gallagher reveals—the Enforcer, the Theologian, the Connoisseur, the Unpackaged Tourist—the first is the best known. The joys of Waugh employing all his (self-acquired) erudition to smack around a witless foe are blatant enough but cherishable for all that. He polished off Stephen Spender—who by virtue of dilettante Marxism and homosexual cruising had acquired a brief, specious reputation for poetic talent—in a single deadly clause: “to see him fumbling with our rich and delicate language is to experience all the horror of seeing a Sèvres vase in the hands of a chimpanzee.” Most writers would have been content with that one coup de grâce, but in the same article Waugh keeps kicking and kicking at the literary cadaver before him. After quoting with approval T.S. Eliot’s gentle rebuke of Spender (“I can understand your wanting to write poems. But I don’t know what you mean by ‘being a poet’”), Waugh snarls:

Mr. Spender knew very well. He meant going to literary luncheons, addressing youth rallies and summer schools, saluting the great and ‘discovering’ the young, adding his name to letters to The Times, flitting about the world to cultural congresses. All the penalties of eminence which real writers shirk Mr. Spender pays with enthusiasm.

In 1935, Waugh had drubbed a bungling biographer of the pre-Raphaelites, who through her sheer incompetence—her many solecisms included confusing Giovanni Bellini the painter with Vincenzo Bellini the composer—goaded Waugh to the following conclusion:

All these faults occur in the first eight and a half pages … On the wrapper of the book it is prominently announced that Miss Winwar has been awarded a £1,000 prize, and that this shocking work was selected from over 800 manuscripts. It is not revealed by whom the prize was offered or who made the selection. Perhaps the name was drawn out of a hat. But if, as it is reasonable to assume, this book was chosen for its superior merit, the mind reels at the thought of the unsuccessful 800.

A subtler demolition job occurs in the spiritual slum-clearance to which Cyril “Palinurus” Connolly’s postwar manifesto inspired Waugh. For years Waugh had combined admiration for Connolly’s style—“phrase after phrase of lapidary form”—with valid aversion to what passed for Connolly’s thought: a mishmash of Freud, Spanish Republican bravado, self-justifying priapism, and physical cowardice. (While the uniformed Waugh faced the Germans in Crete, Connolly was diving under his mistress’s bed at the air-raid siren, proclaiming, “Perfect fear casteth out love.”) Once Cyril hung out his shingle as philosopher-king, Waugh sent the wrecker’s ball hurtling through space:

The significant feature of the Palinurus plan is that none of it makes any sense at all. It has been a hobby among literary men for centuries to describe ideal, theoretical states. There have been numberless ingenious contrivances, some so coherent that it seemed only pure mischance which made them remain mere works of reason and imagination without concrete form. It has been Palinurus’s achievement to produce a plan so full of internal contradictions that it epitomizes the confusion of all his contemporaries. This plan is not the babbling of a secondary-school girl at a youth rally but the written words of the mature and respected leader of the English intellectuals.

Waugh the Theologian offers numerous surprises, including a lack of empathy for the three major Catholic writers (two of them foreign-born) active in his England. Chesterton he censured for carelessness, though Brideshead alludes poignantly to a Father Brown tale, “The Queer Feet.” Belloc’s historiography, as distinct from Belloc’s verse, he dismissed en bloc (“banging about of ideas and a few facts”). “How much was Chesterton,” Waugh wondered, “how much Belloc, driven by financial need to the overproduction which oppressed them …? How much was it the product of a nervous restlessness and sloth? For profusion can be slothful.” As for Roy Campbell, Waugh seems never to have shown him the slightest interest, even before their ways irrevocably parted regarding Franco, at whom Waugh liverishly sniped in one of his weakest stories, “Scott-King’s Modern Europe.” (A provincial streak did mar his ultramontane mind. Upon the occasional mischievous whim, he could and did behave when abroad like the crassest possible lout.) Of Waugh’s few encounters with Catholic intellectuals in Europe, his awkward meeting with Paul Claudel may stand for the rest: “He lacks,” Claudel complained afterwards, “the allure of the true gentleman.”

In his friendships, Waugh sought, above all, singularity and literacy. Almost anyone with those characteristics could warm Waugh’s heart; a Catholic without them could seldom if ever arouse his interest. To most of his co-religionists Waugh much preferred—on both personal and literary grounds—Orwell the stoic, Nancy Mitford the deist, Anthony Powell the tepid Anglican, and Graham Greene the sordid pagan who raided Catholicism’s dress-up box. Even casual intruders occasionally benefited from a charm with which few credited him. James Kirkup, poet and incorrigible pederast, once decided when on a stroll to pick flowers from a hedge. As soon as he did so, a curmudgeonly voice roared forth: “What the bloody hell do you think you’re doing? That’s my hedge!” Suddenly there loomed before Kirkup’s eyes Waugh’s face, empurpled in its ire. The panicky Kirkup (“I felt my knees turn to water”) responded by blurting out the first lines that came to him, from Wordsworth’s “A Poet’s Epitaph.” Waugh’s emollient answer: “I see you are a man of letters. It’s nearly lunchtime. Come and have a sherry.” “Once one got to know [Waugh],” Kirkup recollected, “no one could be nicer.”

* * *

Many an English scribe thinks he understands the U.S. after three days being chauffeured around Manhattan and five days pampered in Hollywood. The rest of the Republic is to him—as “The Simpsons” once put it—“that useless piece of land between New York and Los Angeles. You know, America.” Waugh actually visited, and stayed in, what he died too soon to call “flyover country.” Note the concision with which he captures Louisiana after Mardi Gras:

There is witchcraft in New Orleans, as there was at the court of Mme. de Montespan. Yet it was there that I saw one of the most moving sights of my tour. Ash Wednesday; warm rain falling in streets unsightly with the draggled survivals of carnival. The Roosevelt Hotel overflowing with crapulous tourists planning their return journeys. How many of them knew anything about Lent? But across the way the Jesuit Church was teeming with life all day long; a continuous, dense crowd of all colors and conditions moving up to the altar rails and returning with their foreheads signed with ash. And the old grim message was being repeated over each penitent: ‘Dust thou art and unto dust thou shalt return.’ One grows parched for that straight style of speech in the desert of modern euphemisms…

Nor did this Dead White Male overlook another aspect of piety below the Mason-Dixon line:

One of the things which inspires him [the Catholic visitor] most is the heroic fidelity of the Negro Catholics. … Theirs was a sharper test than the white Catholics had earlier undergone, for here the persecutors were fellow-members in the Household of the Faith. But supernaturally, they knew the character of the Church better than their clergy … honor must never be neglected to those thousands of colored Catholics who so accurately traced their Master’s road amid insult and injury.

Middlebrow media campaigns, at their most virulent in the prole-worshipping Harold Macmillan years, loved to execrate Waugh’s “snobbery.” These campaigns have quietened down to an amazing extent since the Cold War ended, from which fact we can infer the real motivations for vilifying the postwar era’s sole world-renowned native-born Englishman with a complete philosophy to set against “darkness at noon.” Besides, there remains the little matter of Waugh’s imaginative needs. Upward social climbing is entirely compatible with—indeed often a necessary complement to—literary genius: behold Goethe, Stendhal, and Wodehouse as well as Waugh. Downward social climbing, on the other hand, produces only such grotesque artifacts as Auden, Brecht, John Osborne, the senile Tolstoy, and the Republican National Committee.

It is strange that those readiest to denounce Waugh for “elitist” sins that are not sins at all should apparently be blind to Waugh’s gravest and most obvious vice: his creative suicide through protracted alcoholism. No family background or childhood “trauma” (a term he disdained) can account for Waugh’s boozing. Nor, to his credit, did Waugh stoop to the “I blame society” trope when describing his dipso state.

As everyone familiar with Gilbert Pinfold knows, Waugh used grog partly to wash down his industrial-strength sedative intake—although raging insomnia had long been an effect, quite as much as a cause, of his over-indulgences. In a 1964 letter he assured a friend, “I have practically given up drinking.” His concept of near-sobriety comprised (the same letter explains) seven weekly bottles of wine and three weekly bottles of spirits, plus 40 weekly grams of sodium amytal and a weekly bottle of paraldehyde. Contemporaneously, what little cause for wider optimism he possessed had vanished with Vatican II, concerning which he proved incapable of accepting casuistic official bromides about how the conciliar church was just like the preconciliar church, only 100 times better. Once Waugh received a commission to write the life of Swift; although he never tackled this project, he achieved a certain Swiftian climax of his own by suffering his fatal thrombosis while inside a lavatory.

Not only has no younger author taken his place in English letters, no younger author has ever seriously been considered for that place. Even those who can occasionally mimic Waugh’s idiom have shown a complete failure to emulate Waugh’s courage. They routinely drown out their own utterances by the unmistakable sound of backs being scratched. Contemplating him, we may well allude to Wordsworth for our own purposes: “Waugh, thou shouldst be living at this hour: England [and America] hath need of thee.” How many million Africans have starved to death because our masters insisted on reading Frantz Fanon and Willy Brandt—or, worse still, on hailing Dame Bob Geldof as a thinker—when they should instead have been reading Waugh’s Black Mischief? Where is the Waugh of our own day to proclaim what all now know (but few dare admit) about Thatcherism’s true nature: a mere manic, squalid, and saber-toothed variant of the same Servile State which it purported to oppose? What could be more like something out of Vile Bodies’ first draft than the ennoblement of Thatcherism’s best-known advertising sleazebag as “Lord Saatchi”? Who would not enjoy Waugh flagellating Tony Blair, walloping Michael Novak, or overtly marveling at how so many pseudo-conservatives—who preen themselves on their anti-feminism—manage to regard Private Lynndie England with approbation bordering on downright lust?

It could plausibly be argued that the whole of Russell Kirk is contained in a single section from one of Waugh’s supreme masterpieces, Robbery Under Law, where he holds up to his most blistering ridicule the Jacobin gangster regime that had already terrorized Mexico for a generation. (Graham Greene treated this subject in The Power and the Glory, where alone among his novels he approached Waugh’s stature.) The regime’s Jefe Máximo in 1938, Lázaro Cárdenas, threatened Washington with that same mixture of bullying, wheedling, and begging familiar from Vicente Fox’s discourses today. (Although Cárdenas preferred old-style property expropriations to Fox’s demographic warfare.) Robbery Under Law, after treating its readers to one of the most magnificently homicidal anti-Wilsonian enfilades ever fired, concludes thus:

A conservative is not merely an obstructionist who wishes to resist the introduction of novelties; nor is he, as was assumed by most 19th-century parliamentarians, a brake to frivolous experiment. He has positive work to do … Civilization has no force of its own beyond what is given from within. It is under constant assault and it takes most of the energies of civilized man to keep going at all … If [it] falls we shall see not merely the dissolution of a few joint-stock corporations, but of the spiritual and material achievements of our history. There is nothing, except ourselves, to stop our own countries becoming like Mexico. That is the moral, for us, of her decay.

__________________________________________

R.J. Stove lives in Melbourne, Australia.

The American Conservative welcomes letters to the editor.

Send letters to: letters@amconmag.com

Comments