Our First Binge: “Fugitive” Kept TV Audiences Running

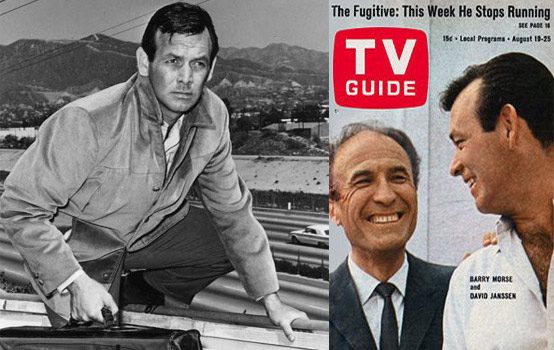

ABC made television history 50 years ago when, on August 29, 1967, it broadcast a definitive conclusion to The Fugitive, the network’s popular dramatic series. The show’s brooding protagonist, Dr. Richard Kimble (David Janssen), on the run after wrongly convicted and then sentenced to death for the murder of his wife, is finally exonerated after narrowly escaping recapture (in nearly every episode). After four years, Kimble clears his name when new evidence establishes the guilt of the real murderer, the elusive One-Armed Man (Bill Raisch).

In a savvy strategy that broke ground for primetime TV but seems commonplace today (see the increasingly used “mini-season” and hype ahead of each final episode), ABC delayed broadcasting the last two episodes of The Fugitive serving as the two-part finale. The network spent four months publicizing the fact that Dr. Kimble would be finally cleared, thus generating wider interest (and water cooler conversation) beyond the show’s devoted fanbase. ABC brilliantly scheduled the episodes for broadcast in late August when there was nothing else to watch on television besides reruns. The Fugitive’s final episode, “The Judgment Part II,” set a ratings record, becoming the most-watched television program until that time. No doubt the show’s fans watched for the emotional satisfaction of seeing their hero set free. Other viewers enticed by the pre-broadcast hype, just tuned in to see something unique that had never been on television before—a major finale.

Before The Fugitive, dramatic television series featured 30-minute or one-hour dramas that usually tied things up at the end of each episode: think Perry Mason’s cases or the Cartwright family’s adventures in Bonanza. The Fugitive built on it’s own history, with characters and plot lines carried over to the next week’s cat-and-mouse chase, all building to the 1967 conclusion. This seems hardly a rarity now but 50 years ago it was a breakthrough.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gA6uOIYoU2M&w=675&h=375]

Not only was the format and finale a first, but Kimble’s exoneration was cathartic for the audience. During television’s first 20 years (1947–1967), canceled shows, including popular, long-running series such as I Love Lucy (1952–1957) and The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet (1952–1966), simply had a “last episode” instead of a “final episode.” Shows driven by a specific plot that had to be resolved simply ended without any resolution. For example, World War II never ended at the end of Combat! (1962–1967) and Twelve O’Clock High (1964–1967). The Robinsons never made it home in Lost in Space (1965–1968). The passengers of the S.S. Minnow remained stranded on Gilligan’s Island (1964–1967) until they were finally rescued (and then re-rescued) in the reunion movies in 1978 and 1979.

Today, sitcoms usually end with two popular characters finally getting together (or back together), a wedding, a birth, or a new job in a new place. Fans watch the final episodes of their favorite dramas, mysteries, and science fiction programs with expectations of seeing questions answered, secrets revealed, loose ends tied up, and major story arcs resolved. Of course that catharsis doesn’t always happen: Several highly-anticipated finales are notorious for bitterly disappointing fans (Seinfeld and The Sopranos), or just confusing them (Lost).

I discovered The Fugitive in the early 1990s when the A&E cable began airing all 120 episodes. Like many people, I was hooked. The Fugitive pushed Alfred Hitchcock’s own recurring theme of “the innocent man wrongly accused” to an extreme. Not only was the title character an innocent man wrongly accused, he was also an innocent man wrongly convicted of murder and sentenced to death.

Actor David Janssen’s played a thoroughly likable Kimble, forced to invent a new alias and a background (for prospective employers) every week. He supports himself by finding menial jobs, most frequently as a bartender, construction worker, truck driver, dishwasher, or farm hand. He always works hard and never robs or cheats anyone. He quickly wins us over by maintaining a strong sense of morality and ethics, even at his own risk. At one point, desperate to avoid capture, he resorts to stealing a man’s wallet to pay for a bus ticket out of town. He later finds a new job, makes the money back, and when he’s safe, returns the wallet by the end of the episode. Several times he risks capture to help someone in need.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FFBPNFUQ4S8&w=675&h=375]

In one first-season episode highly indicative of the growing abortion debate in “the real world,” Kimble encounters a former patient angry over his refusal to abort her pregnancy five years earlier. Instead of a compassionate, good-looking doctor taking care of her “problem,” she charges, the woman was forced to rely on a presumably cold, physically-repulsive “butcher” whose incompetence ensured that she could never conceive another child. “If you had been a human being, if you’d been a man instead of…some kind of two-legged breathing ethic, I might still be in one piece,” she says. Although Kimble doesn’t use contemporary pro-life arguments, he does note the tragedy of abortion by reminding her that “lot of women can’t have children.” While he is sorry for her plight, Kimble makes it clear he is not sorry for refusing her request.

Lt. Philip Gerard (Barry Morse), the police detective who investigated Mrs. Kimble’s murder and was transporting Kimble to prison when their train derailed, allowing for Kimble’s original escape, serves as the show’s chief antagonist. After getting a tip on Kimble’s whereabouts, Lt. Gerard drops everything (including other criminal cases he may pursuing at the moment) to travel hundreds, sometimes thousands of miles, in an effort to recapture him. But in the end, Dr. Kimble would always escape—usually with the assistance of someone who believed in his innocence and helped him slip away.

Although disliked by many viewers for his relentless, nearly obsessive pursuit of Dr. Kimble, Lt. Philip Gerard is actually a dedicated and honest law enforcement official (but a rather neglectful husband and father). He honestly believed the doctor murdered his wife. “The law says he’s guilty,” Gerard explains to one of Kimble’s (many) sympathizers. “I enforce the law.” In the face of new evidence that conclusively points to the One-Armed Man, a career criminal and vagrant, Gerard finally relents (in the last 15 minutes or so), and works with Kimble to clear his name.

Along with the acting, the numerous well-known guest stars, and the overall pacing, William Conrad’s narration, in the title sequences and the beginning and end of all 120 episodes, contributed to The Fugitive’s success and reputation as a classic TV-series. Conrad’s commanding, baritone voice, coupled with his ultra-serious but sympathetic delivery, related Kimble’s desperation, isolation, loneliness, and emotional and physical exhaustion to viewers. As the narrator intones at the end of one episode, “Richard Kimble moves on in search of justice and the elusive privilege of answering to his rightful name.” Despite the terrible injustice done to an innocent man and the apparent bleakness of his plight, the narrator never let the audience forget that there was still hope, which motivated the fugitive to keep running in search of justice and personal vindication. In the final scene, when Dr. Kimble triumphantly walks out of court a free man with his new girlfriend, William Conrad’s narrator is appropriately given the last word: “Tuesday, August 29th. The day the running stopped.”

Dr. Richard Kimble stopped running 50 years ago, but his legacy lives on. The Fugitive inspired a number of subsequent programs with similar themes including Branded, Kung Fu, The Incredible Hulk, The A-Team, and Quantum Leap, and was adapted into a now-classic feature film in 1993 with Harrison Ford and Tommy Lee Jones. Those of us who do not want to see our heroes and favorite characters callously abandoned to unknown fates owe a debt to The Fugitive, which taught the television industry to give their successful and long-running shows a proper farewell.

Dimitri Cavalli is a freelance writer living in New York City.

Comments