Ayn Shrugged

One of the unlikely beneficiaries of the current financial crisis is the estate of Ayn Rand. Sales of Atlas Shrugged, her dystopian classic, have soared in the past year. The book has been solidly in the Amazon bestseller list and briefly edged into that of the New York Times. Not bad for a novel published in 1957. And especially impressive for a work that—viewed purely as literature—must be accounted a disastrous failure.

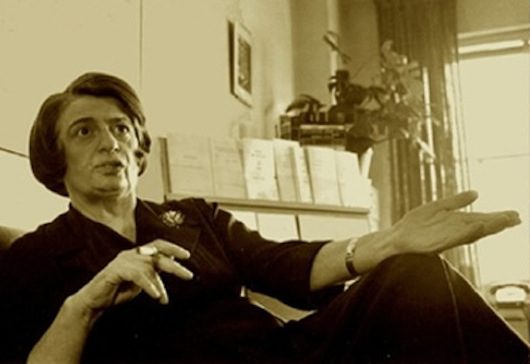

Pace, all you Randians: I am one of you. I have a small picture of the lady on my desk in the European Parliament, next to a signed photograph of Margaret Thatcher, a bust of Thomas Jefferson, and a silver medal from the Ludwig von Mises Institute. The most pleasing compliment paid to me as a politician was when some conservative students started selling a T-shirt with the slogan “Who is Dan Han?”—a reference to the famous opening line of Rand’s magnum opus, “Who is John Galt?”

Rand was a visionary, and her critique of the corporatist order was eerily apt. She argued that her book was prophylactic: a portrayal of a future she wanted to avoid. In some ways, it worked. Very few people argue, nowadays, that economies should be run on the basis of state planning or that socialism is inevitable. In other ways, her analysis of the business-political order—the monopolistic instincts of industrialists, the favoring of back-room deals over open competition, the way party politics punishes integrity and promotes moral cowardice—is eternally true.

In the institutions of the European Union, which were designed by and for bureaucrats and lobbyists, I see Randian scenes being played out every day. Conversations are conducted on the basis of unstated ententes, and directness is considered the height of bad taste. Slogans about the welfare of the citizen are trotted out without thought or meaning, while unspoken plots are hatched against the public weal.

Never mind the EU. Who can meet the directors of a mammoth multinational without thinking of Rand’s description of a company board: “Men who, through the decades of their careers, had relied for their security on keeping their faces blank, their words inconclusive and their clothes impeccable”?

Yet there is no getting away from it: the book simply doesn’t work as a novel. At this stage, I should insert a spoiler warning: the rest of this article will make no sense unless I give away what the book is about. Then again, as we shall see, one of the flaws of Atlas Shrugged is that it is poorly paced. You can see every twist in the plot coming hundreds of pages before you reach it.

Let’s start with the most basic problem. Atlas Shrugged is too long. Way too long. Its point could have been very adequately made in 200 pages rather than the 1,168 of my Penguin edition. Now you might argue that some books need to be long. A novelist who sets out to create a plausible universe, and to people it with developed characters, must give himself room, be he Tolstoy or Tolkien. But there is nothing especially developed about the characters in Atlas Shrugged. They are all more or less interchangeable, speaking in dissertations and behaving in set patterns.

It’s true that the reader travels a long way, morally and politically, between the covers. In the opening pages, we see the railroad chief executive, James Taggart, talking in cliché about the need to “do something for the people,” about there being “higher values than profit.” Toward the end, we see the destructive nihilism of those values. As Taggart hurls a Venetian vase against his wall, we are told,

He had bought that vase for the satisfaction of thinking of all the connoisseurs who could not afford it. Now he experienced the satisfaction of a revenge upon the centuries which had prized it—and the satisfaction of thinking that there were millions of desperate families, any one of whom could have lived for a year on the price of that vase.

That is not a journey on which the reader can be hurried. Had the author baldly stated, “People who talk about non-material virtue and the imperative of need are, in reality, death-cultists who are running away from their own moral emptiness,” the audience would have scoffed. So, yes, a certain amount of space is called for. But having given herself the room, Rand makes little use of it. Her argument is not so much developed as repeated in words that barely alter. It is as though she is trying to push her thesis into us with repeated hammer blows, falling in the same place and with unvaried force.

The novel lacks any sense of movement. We begin and end in a world where nothing works very well. Although there is some mention in the closing chapters of food riots and social breakdown, there is little sense of continuous deterioration. Having at an early stage lost its productive people, the U.S. seems to manage to keep its radio and television networks going, its taxis running, its restaurants serving food. Only in the very final pages do the lights go out.

Nor do the characters develop. They fall into two categories: listless masses and men of action. Those in the former category mill about dully as an undifferentiated supporting cast. Those in the latter group also are interchangeable. Their faces are invariably made of “angular planes.” They speak “without inflection” or “without emotion.” They make up for this by having impossibly communicative eyes. Again and again, we come across absurd passages: “Francisco held his voice flat and steady, but he had the eyes of a man who had had an extra muffin at tea-time, knowing that he really shouldn’t have done, and was now resolved to go for a lengthy country walk, although he half suspected that he would end up pouring himself a generous cocktail when he got home, which would rather take the point out of the whole thing.”

P.G. Wodehouse manages such passages beautifully. Ayn Rand doesn’t. Indeed—again, there is no way of putting this without horrifying her legion of admirers—she isn’t much of a prose stylist. She is especially bad at dialogue, making no attempt at either realism or readability but letting her characters converse in philosophical treatises. Queen Victoria complained that her prime minister, W.E. Gladstone, addressed her as if she were a public meeting. The cast of Atlas Shrugged address each other in a series of essays.

Now you might say that my objection is silly. The book, after all, is a political tract presented in fictional form. But this shouldn’t mean it has to be hard to read. George Orwell, too, was primarily an essayist, and his two bestselling books, Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm, were also political tracts presented as fiction. But both worked as fiction. Both were page-turners.

The same cannot be said of Atlas Shrugged. Apart from anything else, it is marred by small errors. I won’t list them all, since nothing is more tedious to the reader, but they range from irksome failures of research—Francisco d’Anconia is supposed to be descended from a conquistador, so why doesn’t he have a Spanish surname? And why did his ancestor go straight to Buenos Aires, which wasn’t founded until 1580?—to nagging incongruities of plot—if the U.S. is the country where all the productive people have withdrawn their labor, why does it remain solvent when the rest of the world has collapsed? These things are not dealbreakers, of course: follow the plot of, say, “King Lear,” and you’ll find plenty of inconsistencies. But all successful novels depend on pace, on maintaining tension.

And it is here that Atlas Shrugged most fails. Every twist and turn, every deus ex machina, is so ploddingly anticipated as to be robbed of dramatic impact: the identities of Dr. Stadler’s three students, the fate of the inventor of the engine, the name of the worker to whom Eddie Willers pours out his heart, the motives of the figure whom Dagny senses watching her in the shadows, the explanation for Francisco d’Anconia’s apparent hedonism. A friend of mine, a British MP, is on page 800 of Atlas Shrugged as I write. When I mentioned that I was drafting this article, he said, “Don’t tell me, you’ll ruin the plot.” Then he paused and said, “Actually, no, don’t worry: there isn’t a plot. It’s just a series of essays.”

Yes, it is, and therein lies its continuing appeal. Ask a committed Randian about the book, and he will quote one of the set-piece speeches just as a Shakespearean will quote a soliloquy. Neither is primarily interested in the narrative.

Even now, those essays come across as uncompromising. But in 1957, when almost every intellectual was more or less statist, they must have been shocking. Editing the book to make it easier to read would have betrayed one of its chief arguments: that we must live according to our own code and not for the sake of others. The key passage, in this regard, comes from the composer Richard Halley. He abandoned his audience at the height of his success, he explains, because they had wanted him to succeed on their terms, not his. There speaks the authentic authorial voice. No editor would have approved the rough-hewn draft of Atlas Shrugged; all would have pleaded for excisions. But Rand wouldn’t compromise. If readers wanted to benefit from her work, they would have to meet her standards. If not, fine: she owed them nothing.

This creed is stated with a deliberate pitilessness, right up to the closing sentence: “He raised his hand and over the desolate earth he traced in space the sign of the dollar.” But Rand believed that any softening would be a concession to the values she loathed: cant, neediness, the elevation of mercy over justice, of the collective over the individual. In form as well as in content, she tried to give force to her ideals.

“My personal life,” she said, “is a postscript to my novels; it consists of the sentence ‘And I mean it’.” Yes, we believe you. That’s why, whatever its shortcomings as a novel, we still buy your book. That’s why you have influenced generations of undergraduates—in the U.S., at least, if not on my side of the Atlantic. And that’s why I pay you the highest tribute: if your ideas seem less outré now than when they were written, it is because of the influence of your oeuvre.

Daniel Hannan is a British Conservative Member of the European Parliament.

Comments