An Affordable-Housing Fix

The city-planning movement known as New Urbanism is no longer the new kid on the block. For more than 30 years, its apostles have been preaching a gospel of mixed-use, walkable neighborhoods with accessible public spaces and a variety of housing types. But this call for a return to traditional forms has yet to achieve its ambition of once again becoming the default mode of residential development and community design. One of the most significant obstacles standing between New Urbanism and mainstream acceptance is a perceived lack of affordability.

To a great extent, the movement retains an air of inaccessibility or even unreality. The average person likely associates it with well-heeled resort towns in the mountains or on the coasts. Perhaps the most famous example is the early New Urbanist development of Seaside, Florida, a beach town recognizable around the world as Jim Carrey’s dystopia in the 1998 film The Truman Show. Yet since its inception, New Urbanism’s promoters have sought to develop not only camera-ready locales for the most prosperous but communities all over the country that are accessible to residents of varying incomes and stages of life.

The “Charter of the New Urbanism,” a set of principles agreed to by the movement’s leading architects and developers, stresses the importance of income diversity and a variety of housing types within neighborhoods. But a casual perusal of real-estate listings in almost any New Urbanist community would give most median-income households a nasty case of sticker shock. To examine this problem and find possible solutions, it’s best to focus on projects in housing markets where most people live. A three-hour drive north of Seaside, but a world away from the resort vibe of the Florida coast, one finds one such typical development, the Hampstead neighborhood in Montgomery, Alabama.

Montgomery is an average city in many respects. Its population falls just short of placing it in America’s top 100 cities. Politically the city is an island of Democratic blue in a sea of Republican red. The median household income is very close to that of the country as a whole. Its economy is fairly well diversified, with government (including the military), manufacturing, tourism, and services all playing significant roles. It seems reasonable to assume that if New Urbanist communities can succeed in Montgomery, they can do so throughout the heartland and the Bible Belt.

In fact the Hampstead development has thrived—to a point. Begun in 2005 at the height of the real estate bubble, it launched with the goal of quickly developing its 400-plus acres on the outskirts of the city. Its planner was Duany Plater Zyberk & Company (DPZ), the designer of Seaside and the closest thing to a celebrity firm in the world of New Urbanism. After the housing crash, development proceeded at a more moderate pace, recently entering its fourth phase of construction.

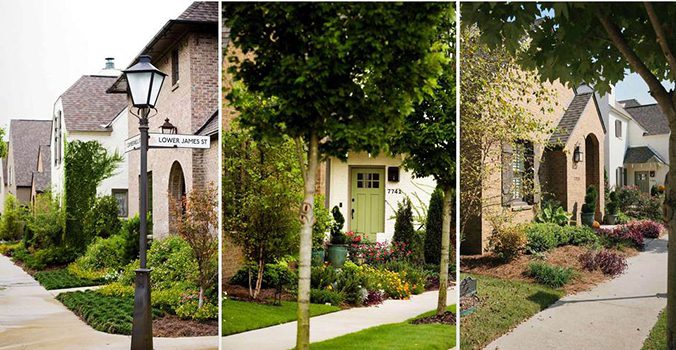

The neighborhood features many staples of New Urbanism: a “town center” with several small businesses, green spaces of various sizes, an urban farm, pools and playgrounds, and streets with a pedestrian-friendly design. It also boasts the largest lake in Montgomery, branches of the public library and YMCA, and a Montessori school.,

These features all come with price tags, and Hampstead’s developers have had limited success producing affordable housing. The neighborhood’s smallest detached homes list for roughly 50 percent above the area’s median home price and more than four times the area’s median household income. Compared with other new construction in the area, Hampstead’s price per square foot exceeds the average by about a third. Tack on homeowner-association fees equivalent to about 2 percent of median household income, and owning a house in Hampstead becomes a proposition most Montgomery residents cannot afford.

Harvi Sahota and Anna Lowder, the directors of design and development at Hampstead, acknowledge that affordability is a problem. The challenge was even more acute in the early stages of the project, when the least expensive detached homes were priced tens of thousands of dollars above the smaller ones available today. According to Sahota, up-front infrastructure costs for New Urbanist developments are relatively high, and to recoup those costs developers are pressured to keep home prices high in the initial phase. “To take just one example,” he notes, “your typical developer builds a cul-de-sac where utilities can be installed cheaply at the front of the lots. We build alleys at the rear of the lots and run all the utilities behind the houses, which is much more expensive.”

As Sahota and Lowder sought to expand the price range of newly constructed homes after the initial phase, they encountered a further obstacle to affordable housing in Hampstead: some of the residents themselves. In 2015, the developers announced plans to build a handful of single-family homes without garages on less expensive lots near the edge of the neighborhood. “We wanted to reach a broader market, offer something to young families with two or three children who needed square footage but might not be able to afford the homes with more features in the heart of the neighborhood,” Sahota said. The announcement, which advertised the planned homes as “affordable,” provoked fierce resistance from many residents. “It was a fireworks storm,” Lowder recalled. “These homes still would have been priced far above the local average levels, but people heard the word ‘affordable’ and thought it would be detrimental to their own home values.”

Ultimately the developers canceled plans for the more affordable homes, but they soon returned with plans for condominiums and apartments that had the potential to broaden the income diversity of the neighborhood’s residents. David Peden, a Hampstead resident who manages residential leasing for the apartments, says that history repeated itself to some extent. “There was a lot of blowback from neighborhood residents when we announced the apartments, even though we were planning to charge some of the highest rents in the city.”

This time the planners resisted the blowback and followed through on construction despite residents’ complaints. But Peden acknowledges that the apartments, which were completed in the autumn of 2016, have not yet had a big impact on the neighborhood’s income diversity. “We’ve attracted more young folks who may not have saved enough for a down payment on a house, but applicants still need a strong credit history to lease from us. I’d guess that most of them make above the area’s median income.”

DPZ co-founder Andrés Duany says that part of New Urbanism’s nationwide affordability problem comes from the fact that the housing stock in these developments is relatively new. The reselling of older homes in more established neighborhoods has always helped increase affordability. Still, Duany insists that the problem also stems from a persistent imbalance in supply and demand resulting from an overly restrictive regulatory environment. “We have found over the years that 30 to 60 percent of any market will actually welcome New Urbanism. However, because it is so hard to provide it is always scarce.” In many municipalities, building codes and standards for street planning and the like simply make New Urbanist neighborhood design illegal without a variance. The “SmartCode” developed by DPZ to help local governments make standing provisions for New Urbanist developments has been available since 2003, but most cities have not yet adopted it.

According to Duany, Montgomery is the only U.S. city that currently has a New Urbanist code for both inner-city and suburban development—and it’s thanks to Sahota and Lowder, whom he calls “heroic.” Lowder recalls the 2005 campaign to persuade the city to adopt the SmartCode as a major public-relations initiative. “We hosted an eight-day event to showcase the plan for Hampstead. Every public official was invited, every department of the city. We invited the public. All the surrounding neighbors and landowners were part of that process. They welcomed the design and the concept. But we told everyone we would only make the investment if the SmartCode was enacted as a zoning code for the city.” Duany says developers in other cities will need to launch similar campaigns if New Urbanism is to have a “level playing field.”

Even with the SmartCode in place, though, a neighborhood like Hampstead struggles to offer affordable housing. Duany again cites the regulatory burden, this time of the sort faced by all developers, as the chief culprit. “A century ago we housed millions of poor immigrants with no government assistance. Now at the local level we have these life safety codes—the handicap code, the fire code, the sprinkler code. They all cater to the expectation that the world shall be perfect, and they add enormously to the burden.” He concludes that the “government has made affordable housing impossible, such that it can only be delivered with the help of the government. It prevents it from happening organically.”

Regulatory relief in this area would not necessarily make New Urbanism more competitive with other types of development, but in absolute terms it could open the door to more potential homebuyers. Lowder agrees, recommending that developers be willing “to push a municipality to consider less expensive engineering requirements. We have gold-plated infrastructure here in Hampstead. Because the implementation of the SmartCode was so new in 2005, we didn’t push in this area, but there’s a lot of money under these roads. If you’re able to reduce that cost, you can deliver a more affordable product.”

Sahota and Lowder have other ideas on how developers can increase affordability even without further regulatory relief. Sahota notes that after the financial crisis, the SmartCode adapted to permit less expensive upfront costs. “In our initial phase, we had to put a very significant investment into the first two commercial buildings in our town center. The newer code would have allowed us to develop the center more rapidly at perhaps one-fourth the cost by building one-story, flat-roofed temporary structures with brick facades for retail and other commercial space.” Then developers “could have replaced the temporary buildings after ten years with the impressive two-story buildings we have now, after giving the early residential phases a nice boost.”

Lowder adds that developers can offer a wider range of price points to homebuyers by developing multiple phases with residential lots of different quality simultaneously. “Looking back, we should have worked earlier on some of the less expensive lots we’re just now reaching in Phase Four. They could have served as a loss-leader to get more people into the neighborhood.” She also acknowledges that building more inexpensive houses early in development could have helped them avoid the conflict with residents who complained about later phases of planned construction that included new homes priced below existing neighborhood averages.

Ultimately, New Urbanism’s promoters must do a better job explaining to consumers that they are paying for more than a home. Forrest Meadows, Hampstead’s designated real estate agent, notes that although internet research has helped make his potential customers more informed than ever, many of them have not thought through the tradeoffs that a New Urbanist neighborhood offers. “We’re selling a change in lifestyle here,” he says. “People often realize after seeing the neighborhood and talking with me that they could do without some of the things on their wish lists and be happy with less square footage because of everything Hampstead offers within walking distance.”

Lowder doubts that Hampstead will eventually provide pedestrian access to all of its residents’ daily needs. “People will always have cars in Montgomery,” she concedes. At the same time, Sahota insists that even in its current phase of development, the neighborhood’s features make it feasible for many multi-car families to consider giving up one of their vehicles. Plans for construction of co-work commercial space for owners of small businesses will increase opportunities for Hampstead residents to walk to work.

Duany agrees. “One less car. That’s a choice New Urbanism makes possible,” he says. “A family that can do away with one vehicle and save maybe $10,000 a year on payments, fuel, insurance, and taxes has much greater flexibility in choosing its house.” That savings, he explains, is “not a calculation most potential homebuyers make until it’s pointed out to them. Suddenly New Urbanism seems much more affordable.” He expresses optimism that in the coming years two demographic groups will drive New Urbanism’s marketability: aging baby boomers who need independence from cars, and millennials who were never attached to cars in the first place.

No silver-bullet solution exists for New Urbanism’s affordability problem. But a combination of pragmatic reforms—regulatory relief, more efficient development, and consumer education—could provide a way forward for the maturing movement as it moves closer to the mainstream of American real estate.

Jason Jewell is a professor of humanities at Faulkner University.

Comments