Why Rebuild a Gothic ‘Addition’ to Notre Dame?

Two days after the horrific fire at the most beloved Gothic cathedral in the world Prime Minister Philippe announced a competition to replace the spire. Why would we replace the historic cathedral spire unless it was ugly, poorly constructed, or incongruous with the cathedral? A few days later, we saw the first of many designs exhibiting a greenhouse and a glass and steel spire denuded of all reference to the masterpiece. What should be done with Notre Dame’s spire?

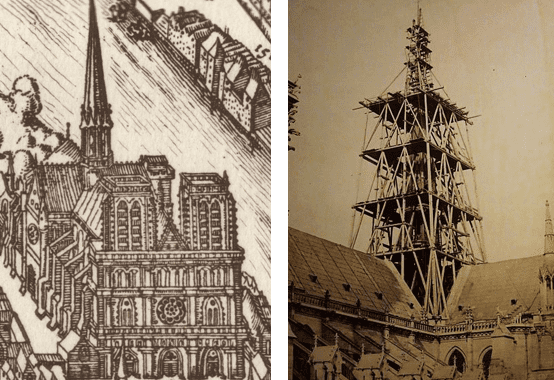

First we need to understand the history of the spire. An earlier spire in danger of falling was dismantled in 1786 and the French revolution assured that it was not rebuilt. Only when the cathedral was restored seventy years later was a new spire added. That second spire is the one that was destroyed during Holy Week.

The spire — in architectural terms, the flèche or arrow — is typically a metal tower with a conical roof placed at a crossing or on top of another tower. New Yorkers can see them on various churches throughout the city. At Notre Dame the flèche marked the crossing, where the nave and transept meet. It pointed up to the heavens like an arrow for which it is named.

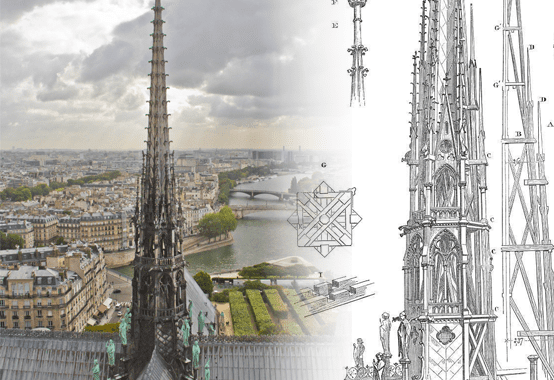

The architect, Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, created something new but in the original style. After a study of historic towers, he determined that Notre Dame required a flèche equal to the height of the main church body which is 150 feet tall. At 305 feet above the ground, its only rival in Paris until recently was the great spire by Eiffel. Thanks to the wonderful Parisian height limit the flèche can seen from around the city, most romantically from the banks of the Seine. A gray metallic pinnacle, the flèche seemed to grow organically out of the roof, while its design was in perfect keeping with the stained-glass windows and the flying buttresses below.

In the 1850s, the new spire was beautifully hand-crafted out of 50 tons of lead over a wooden armature weighing 180 tons. This hidden oak structure was part of the attic structure, which helps explain why the fire brought down the spire so quickly. The octagonal base of the spire was surrounded by larger than life statues of the apostles and evangelists, fortuitously removed before the fire. Above them, two levels of pointed arches were crowned by gables and gargoyles. Tall pinnacles at the corners ring the pièce de résistance, the tall conical roof covered with croqs or crockets, inspired by the “crook” of a bishop. On top of the croq covered roof is a large cross topped by a coq (rooster).

The spire’s delicate and open tracery contrasted with the massive stone of the nave while the spire’s height and location balanced out the front two towers. Artists throughout the centuries have captured the elegance and picturesque quality of Viollet’s spire from around the city. Not all Gothic cathedrals have a spire at the crossing, and this is one of the many elements that sets Notre Dame and Viollet-le-Duc’s design masterfully apart.

One does not have to be a Gothicist to appreciate Viollet-le-Duc’s restoration of Notre Dame. One of the most influential architects of the 19th century, he is best known for his restorations and harmonious additions to Gothic structures. He has also been criticized by historians and purists for taking liberties with historic buildings and “improving” them rather than merely rebuilding them. In this, Viollet did what most talented architects in the Gothic period would have done. Perhaps his great sin was to call a sympathetic addition a “restoration.” However, one does not have to agree with his theories of restoration to see that Viollet’s flèche at Notre Dame was an original yet seamless addition to a magnificent cathedral. Up until its fiery destruction, no sane person was calling for its removal.

Now what shall be done, with the flèche and indeed with much of the whole building needing to be restored? Prime Minister Edouard Philippe and the architectural community want to build something new, something that looks 21st century. Why not a glass and steel tower, an asymmetrical shard, a diamond-tipped laser going up to the sky? Is that not what Viollet-le-Duc and the great Gothic architects before him would have done if they could have? Wouldn’t they have built in the spirit of the times?

Yes and no. Viollet and his forbears certainly sought to develop contemporary solutions for Gothic architecture such as missing spires. Sometimes this resulted in new designs, as it did in Viollet’s flèche, or modifications to the original, as it did in much of the rest of the cathedral. But they did so in humility towards the construction methods and artistry of the original. Yes, Viollet felt that he could make a better spire than the one that had been pulled down in 1786, but then he also knew how to speak the language of Gothic architecture fluently.

So why not allow contemporary architects to try their own hand at building a spire on top of the most important house of God in France? First, because Viollet’s spire is a great work of architecture on a world heritage site, and secondly because most contemporary architects couldn’t design Gothic to save their life. Those architects who have tried to design using the Gothic or Classical languages today will humbly admit the brilliance and timelessness of Viollet’s work. If you don’t agree, please name ten Gothic spires, from anywhere and anytime, that are considered more beautiful than Notre Dame’s spire.

This returns us to the original question of what to do with Notre Dame and all of the contemporary architects who cannot wait to get their hands on it? Notre Dame deserves a harmonious spire worthy of this great cathedral not an ugly, incongruous spike. As for the architects, they should have the freedom to experiment somewhere else.

Duncan Stroik is a professor of architecture at the University of Notre Dame, in the U.S., and an architect who focuses on church architecture.

Comments